The possibility that people of color could be shifting away from the Democratic Party – sometimes called a “racial realignment“ – is one of the hottest topics in American politics right now. A shift was evident in the 2020 presidential election, as Black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans were a bit more likely to vote for Donald Trump than they had been in 2016, although most of each group voted for Biden. Current polling suggests even larger shifts heading into 2024.

To some commentators, these shifts or potential shifts mean that race is somehow becoming less important to politics or to Donald Trump’s appeal in particular.

In the New York Times, David Leonhardt recently made this argument. He said that any rightward shift among people of color means that the idea that Trump’s appeal is “all racial resentment” is not “merely questionable” but “wrong.” He argued that Trump’s appeal to “working class” people of color means that we should understand their voting behavior in terms of class rather than race. (Bill Maher recently said the same thing.)

There is a crucial problem with this argument. It fails to separate two things: Which racial group voters belong to and how voters feel about racial issues. In Leonhardt’s telling, if racial groups are less polarized, then racial issues (“racial resentment”) matter less.

In fact, the opposite is true. While American politics may now be less polarized by race, it is more polarized about race.

Racial attitudes among people of color

Many studies have examined racial attitudes among different racial and ethnic groups in the United States. A common finding is that Black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans do not have consistently liberal or progressive attitudes about race and racial issues. Nor do they necessarily share a common identity or sense of solidarity with each other.

For example, more than 30 years ago, political scientist Louis DiSipio analyzed some of the first national surveys of Latinos in the U.S. He found that although Latinos of various national origin groups tended to have progressive views on many issues, some did not – even on issues directly relevant to their ethnic group. Among Latinos who were U.S. citizens, about 45% favored making English the national language – far fewer than among white citizens but still a substantial proportion.

This diversity in political attitudes among Latinos persists. The 2020 American National Election Study asked whether the U.S. should increase, decrease, or keep the same level of immigration. About 36% of Latinos wanted to increase it, 44% wanted to keep it the same, and 20% wanted to decrease it.

Similarly, although Black Americans express different views of racial inequality than do white Americans – for example, Black Americans are less likely to attribute racial inequality to a lack of effort by Black people – such sentiments are not absent either. The 2020 American National Election Study asked whether respondents agreed that “if blacks would only try harder they could be just as well off as whites.” Most Black respondents disagreed, but 15% expressed a neutral attitude and 13% agreed.

Other work has examined how different racial groups feel about each other and, in particular, the challenges of generating solidarity among minoritized groups. There is research on anti-Black attitudes among Latinos and Asian Americans, anti-Latino attitudes among Black people, and so on. The lack of solidarity can arise because minoritized groups perceive that they are in competition with each other for economic resources. Or, as recent research by political scientists Efrén Pérez, Crystal Robinson, and Bianca Vicuña shows, it can arise because of insecurity about one’s status as a member of the broader American community.

If we want to take seriously the politics of race and ethnicity in this country, we have to do more than divide people into racial groups. We have to know what people believe about racial groups and racial issues – and how their beliefs translate into political choices.

How Trump built support among racially conservative voters of color

A first place to see how racial attitudes translated into political choices is the 2020 presidential election. We’ll compare how different racial and ethnic groups voted in 2016 and 2020, drawing on the Cooperative Election Study (CES). The CES has large samples of these groups and shows the same shift toward Trump among voters of color documented elsewhere.

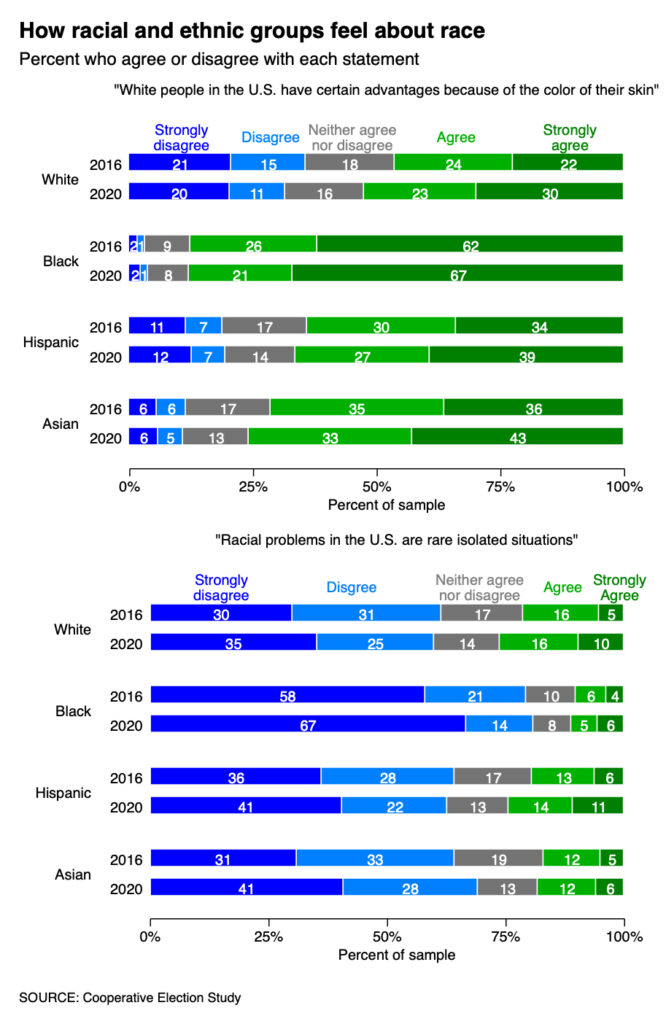

Both the 2016 and 2020 CES surveys included two questions about race in the United States. The surveys asked whether respondents agreed or disagreed with two statements: “White people in the U.S. have certain advantages because of the color of their skin” and “Racial problems in the U.S. are rare, isolated incidents.” (For more about these questions, see this study.)

Below is the distribution of attitudes for both questions, broken down by year and racial group:

Unsurprisingly, people of color are more likely than white respondents to believe that white people have advantages and to disagree that racial problems are rare and isolated.

But not all people of color feel this way. For example, in 2020 about 11% of Black people, 33% of Latinos, and 24% of Asian Americans either disagreed that white people have an advantage or expressed no opinion. Similarly, between 19-38% of these groups agreed that racial problems are isolated or expressed no opinion.

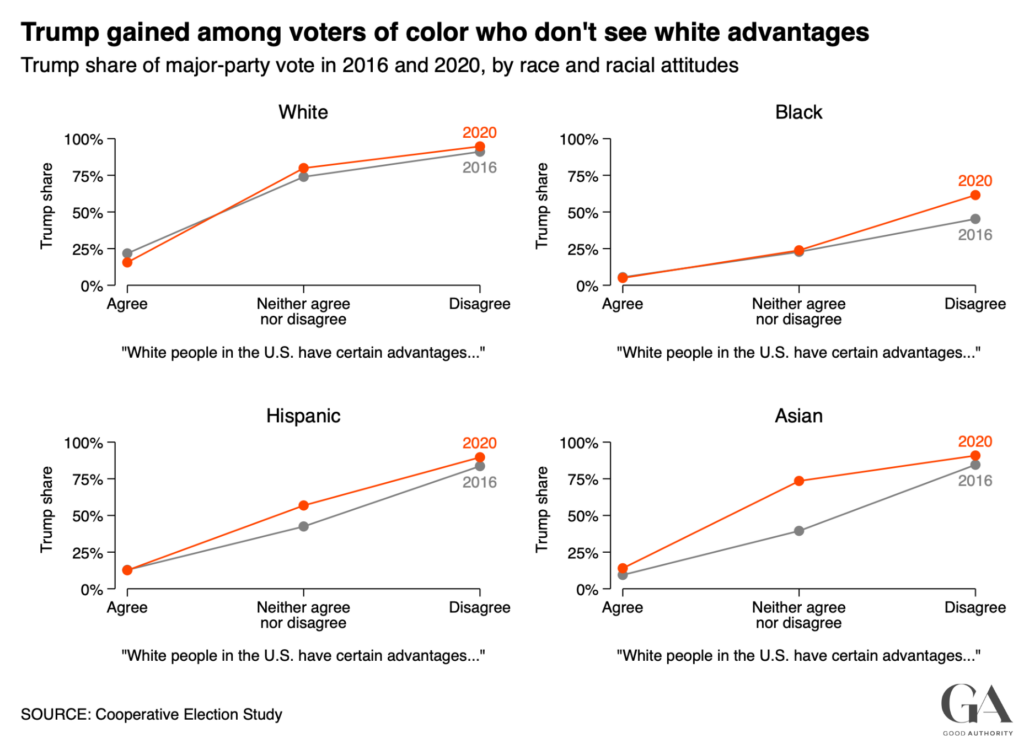

These are the voters of color who were more likely to shift to Trump between 2016 and 2020. The graph below shows that Trump gained votes in 2020 among Black, Latino, and Asian voters who strongly disagree or disagreed that white people had an advantage or neither agreed nor disagreed:

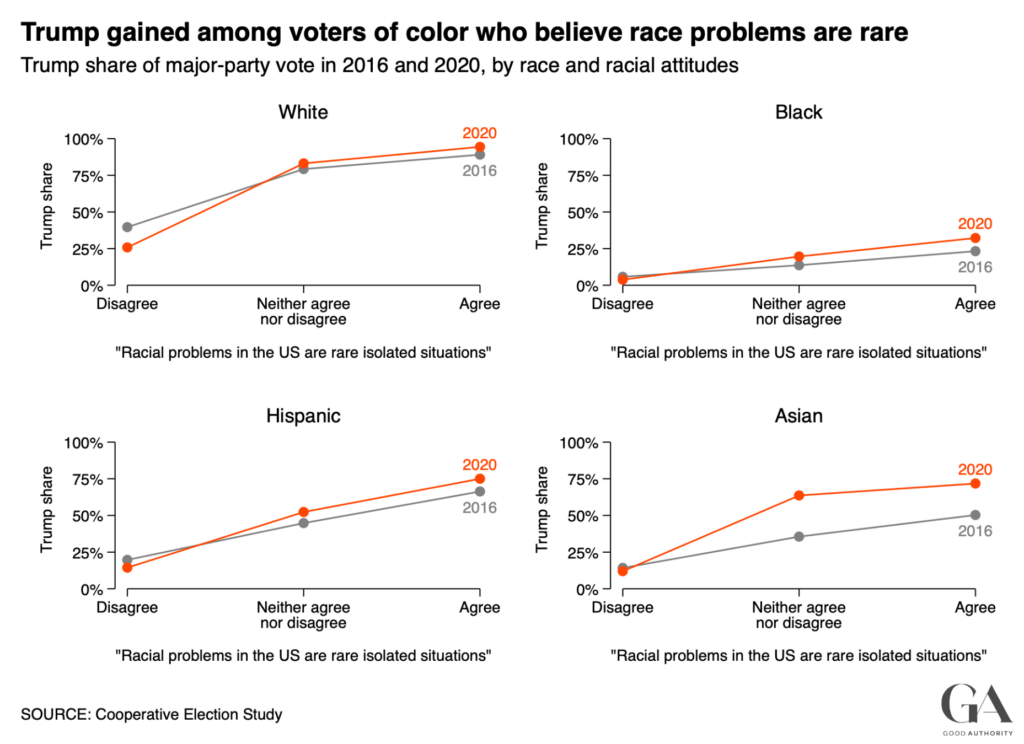

The graph below shows that Trump gained votes in 2020 among Black, Latino, and Asian voters who thought racial problems were rare and isolated:

These results square with other analyses. For example, a detailed study of Latino voting patterns in 2016 and 2020 by political scientists Bernard Fraga, Yamil Velez, and Emily West found that Trump gained votes among Latinos with conservative views of racial issues – in particular, immigration and criminal justice policy.

As a consequence, racial attitudes appeared to matter more in 2020 than 2016. You can see this by comparing the orange lines to the gray lines: The orange lines are steeper.

So, even as people of color moved somewhat toward the Republican Party in 2020 and the electorate became less polarized in terms of race, it became more polarized in terms of racial attitudes.

Latinos who are less sympathetic to Black Americans are shifting away from the Democratic Party

Here is a second piece of evidence for our argument. It’s about the trends in the party identification of Latinos between 2019 and 2022, and how these relate to Latinos’ view of equal rights for Black Americans.

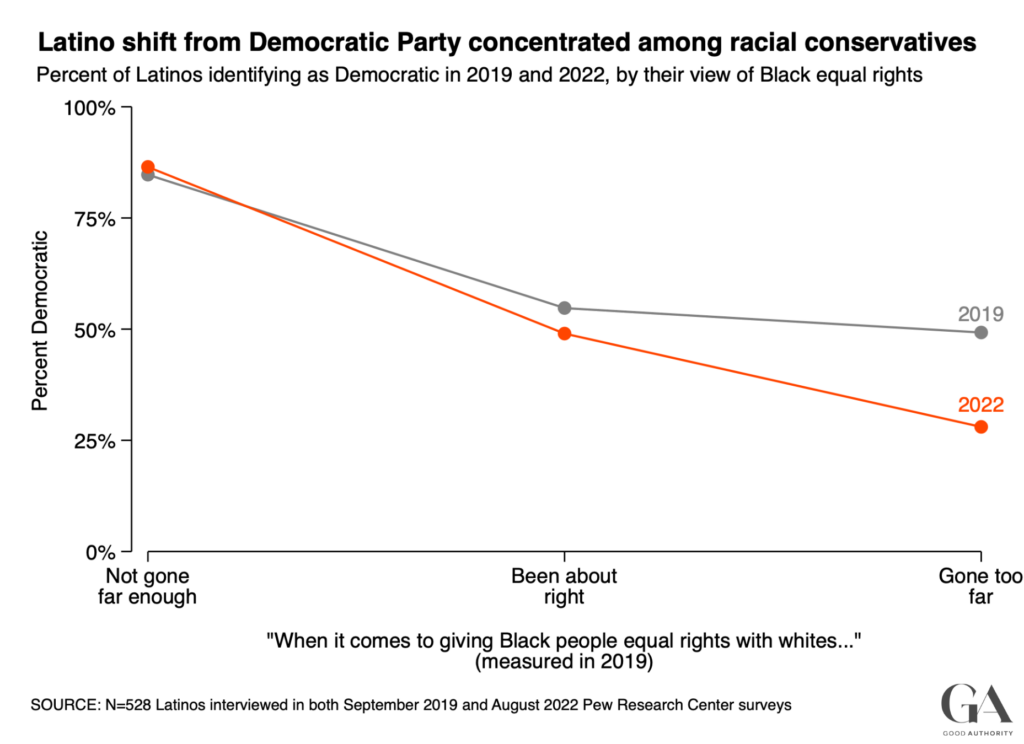

Our data combine two different Pew Research Center surveys. The first, from August 2019, interviewed a nationally representative sample from Pew’s American Trends Panel. This survey asked about people’s party identification and also their views on this question: “When it comes to giving Black people equal rights with white people, do you think our country has gone too far, not gone far enough, or has it been about right?”

Among Latino respondents in this survey, 48% said “not gone far enough,” 41% said “been about right,” and 10% said “gone too far.” Thus, about half of Latinos did not see any need to go further in promoting the equal rights of Black Americans.

In August 2022, Pew conducted a National Survey of Latinos. Fortunately, we were able to identify 528 Latino respondents interviewed in both surveys. We can compare how Latino partisanship changed between 2019 and 2022 based on their views of Black Americans’ equal rights in 2019.

Note that by looking at the same group of respondents three years apart and using a 2019 measure of racial attitudes, we are guarding against the possibility that Latinos simply changed their racial attitudes because they changed their partisanship. Our analysis of the Trump vote in 2016 and 2020 is vulnerable to that possibility because the CES survey did not interview the same respondents in both years.

Among the Latinos interviewed in both surveys, almost 70% identified with or leaned toward the Democratic party in 2019. By 2022, this dropped modestly to about 64%. Republican partisanship increased by roughly the same amount. So the majority of Latinos remained Democratic, but that majority was slightly smaller in 2022 than in 2019.

Here is how this 2019 question about equal rights for Black people was related to Democratic partisanship among Latinos in both 2019 and 2022:

All the Latinos surveyed who shifted to the GOP express a sanguine view of equal rights for Black people, saying either that we’ve done enough or even gone too far. So, once again, Republican gains are concentrated among racially conservative Latinos. And, once again, an important measure of racial attitudes is becoming more predictive of partisanship, even in an era where partisanship may be less polarized based on racial group membership.

The takeaway

Note that we have been making descriptive claims, not causal claims. We have shown what kinds of people of color may be shifting to the Republican Party. They are people with more conservative attitudes on race. But this does not mean that racial attitudes are causing these shifts, or, if they are, that racial attitudes are the only factor.

But at the same time, it is premature to attribute these shifts among voters of color to “class” or to being “working class.” Any measures of class – income, education, occupation, etc. – is conflated with attitudes. People with different educational backgrounds may be of different social classes, but they will also have different beliefs about any number of issues, and especially racial issues.

Ultimately, our findings provide an important reinterpretation of any “racial realignment” in the U.S. If voters of color are shifting durably toward the Republican Party, this most certainly does not make race less important, if race is defined as “what people think” not just “what group they belong to.”

In fact, racial attitudes are becoming more strongly correlated with political attitudes, among white voters and voters of color alike.