Last week, the commander-in-chief of Ukraine’s military acknowledged that the country’s counteroffensive has stalled. Even though Ukraine’s government insists it will continue its operations through winter, increased cold and mud means any offensive will be slow going.

Some observers believe the bogged-down offensive means the time has come for Ukraine and Russia to seek a negotiated settlement. Some estimate that the war has already killed or injured 500,000 soldiers and civilians. The World Bank estimates the war has done $135 billion in damage to Ukraine’s infrastructure. While European aid remains robust, as the war drags on, Ukraine’s supporters are increasingly concerned that critical U.S. support will wane. And as the U.S. Congress heads toward another shutdown battle over the federal budget, Republicans are poised to block additional funding for Ukraine.

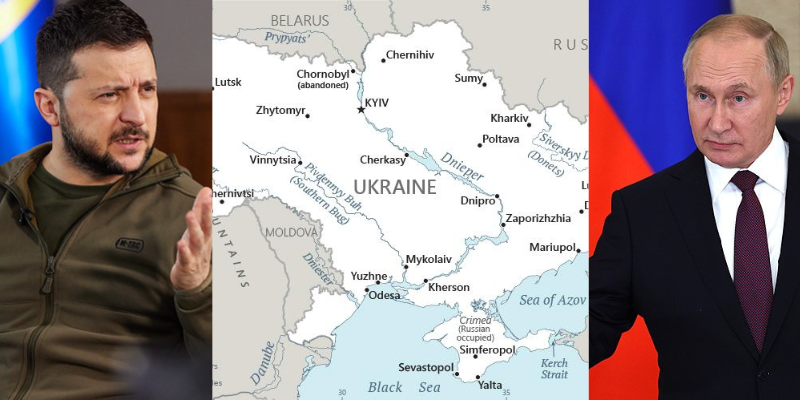

In fact, some news media outlets are reporting that the U.S. and European officials have broached the question of a negotiated settlement with the Ukrainian government. Negotiations, some experts maintain, are the only way out. Yet any settlement would involve significant territorial compromise. Most likely, negotiations would result in leaving Russia in charge of Ukrainian territory it currently occupies.

Critics of this approach reject territorial negotiation as unwise, even morally repugnant. Allowing Russia to freeze the status quo would only reward its aggression. It also risks setting a precedent that would encourage others to violate norms of territorial integrity. But even without these concerns, research suggests Ukraine and Russia will find it almost impossible to compromise on territorial boundaries.

Neither side can make credible commitments

First, what political scientists call “commitment problems” – a country’s inability to credibly commit to an agreement – are likely to hinder a territorial settlement. Even if Ukraine and Russia can agree on a solution in the present, few if any mechanisms would prevent either side from attempting to change the status quo later on. Both sides will find it difficult to agree to a territorial compromise when neither believes their opponent will preserve the status quo.

Ukraine’s concerns about Russian commitments are straightforward. Putin has provided no signal that he respects territorial settlements. While Russia claims it is interested in negotiating an end to the war, it has simultaneously refused to offer concessions.

But Russia also has reason to question Ukraine’s ability to commit to compromise. Those who support negotiations maintain that a territorial settlement with Russia will be better for Ukraine in the long run. Here’s their argument: If Ukraine ends the conflict and accepts the status quo, Ukraine can begin to rebuild its economy, build closer ties with NATO, and perhaps even join the European Union.

But this trajectory is precisely what Russia fears. Research suggests that commitment problems are even more severe when an agreement is likely to shift power from one country to another. If Ukraine leverages the peace to increase its military and economic power, its leaders could use this newfound strength to overturn the territorial status quo.

To take one particularly fraught example: If NATO would offer Ukraine membership, this would certainly assuage Ukraine’s fears that Russia would renege on a territorial settlement. But the possibility of NATO membership only increases Russia’s concerns that Ukraine will eventually have the power to overturn any negotiated settlement. Paradoxically, the benefits that make Ukraine more likely to negotiate might undercut Russia’s interest in doing so.

Russia and Ukraine have expanded their war aims

A second problem is that, during conflicts, countries expand their war aims, including territorial claims, and thus reduce room for compromise. Russia now controls about 18% of Ukraine’s territory. It has shown little signs of walking back its demands that other countries recognize as Russian the territories it claimed in September 2022. Whereas Ukraine’s leaders may have grudgingly accepted Russian occupation of Crimea and Eastern Ukraine before the invasion, its leaders now demand that Russia must withdraw from all its territory.

Political scientists argue that fighting leads to an expansion of territorial claims, for a number of reasons. Authoritarian leaders are likely to increase their demands in hopes of securing their political position at home. Losing war comes with significant political costs. For an authoritarian leader, those costs might be deadly. Being able to show the public that a war increased the country’s territory provides insurance against bad outcomes. In the wake of the Wagner Group’s mutiny last summer, these domestic challenges are most certainly on Putin’s mind.

Second, sunk costs – the blood and treasure a country has already spent on war – make leaders less prone to compromise with their opponents. Rationally, leaders should worry not about past costs, but whether fighting is worth the future human and economic losses. But this is rarely the way decision makers think about the costs of fighting. Instead, politicians justify continued fighting by referring to lives already lost.

Both Russia and Ukraine see the territory as indivisible

Finally, territorial compromise also may be off the table if both Ukraine and Russia see currently occupied territories as indivisible. A negotiated settlement that freezes the status quo would accept the division of Ukraine’s territory. Supporters of negotiation hope that an offer of “side payments” might facilitate a deal. For instance, Ukraine might be willing to accept the loss of territory if the U.S. and Europe offer significant economic investment and security commitments as compensation, particularly membership in the E.U. and NATO.

But for Ukraine’s supporters to offer side payments, Ukraine must be amenable to territorial tradeoffs. While this is sometimes the case, frequently the parties involved refuse to see territory as divisible – whether through partition, shared sovereignty, compensation, or any other mechanisms. When territory is indivisible, compromise becomes difficult, if not impossible, as seen in cases as diverse as Jerusalem, Kashmir, and Northern Ireland.

Scholars have identified numerous mechanisms that make territory indivisible. In some cases, such as in Jerusalem, the public comes to perceive territory as sacred, an inviolable part of a homeland. Both Russian and Ukrainian leaders have used such rhetoric to describe their claims to Ukrainian territory. Putin has claimed Russia and Ukraine are inhabiting the same “spiritual space.” He argues that Ukraine only exists because the Bolsheviks divided Russia, “tearing from her pieces of her own historical territory.” Whether or not Putin’s rhetoric is sincere, these claims resonate with his population.

In other cases, leaders refuse to divide territory for fear it will undermine the government’s legitimacy. Many Indian officials believe that compromise over Kashmir would undermine India’s legitimacy as a multiethnic, multi-religious democracy. Likewise, Ukraine is home to numerous ethnicities. If Ukraine were to accept Russia’s occupation of one part of its territory, this could risk a legitimacy crisis. Ukraine’s government maintains that it can legitimately govern a multiethnic state that is “indivisible and inviolable.”

There are many roads to intractable territorial disputes. Unfortunately, the conflict between Russia and Ukraine seems to be traveling on all of them.