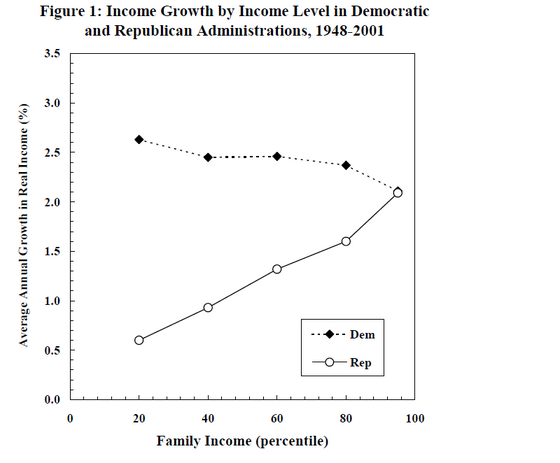

A few years ago Larry Bartels presented this graph, a version of which latter appeared in his book Unequal Democracy:

Larry looked at the data in a number of ways, and the evidence seemed convincing that, at least in the short term, the Democrats were better than Republicans for the economy. This is consistent with Democrats’ general policies of lowering unemployment, as compared to Republicans lowering inflation, and, by comparing first-term to second-term presidents, he found that the result couldn’t simply be explained as a rebound or alternation pattern.

The question then arose, why have the Republicans won so many elections? Why aren’t the Democrats consistently dominating? Non-economic issues are part of the story, of course, but lots of evidence shows the economy to be a key concern for voters, so it’s still hard to see how, with a pattern such as shown above, the Republicans could keep winning.

Larry had some explanations, largely having to do with timing: under Democratic presidents the economy tended to improve at the beginning of the four-year term, while gains under Republicans tended to occur in years 3 and 4–just in time for the next campaign!

See here for further discussion (from five years ago) of Larry’s ideas from the perspective of the history of the past 60 years.

Enter Campbell

Jim Campbell recently wrote an article, to appear this week in The Forum (the link should become active once the issue is officially published) claiming that Bartels is all wrong–or, more precisely, that Bartels’s finding of systematic differences in performance between Democratic and Republican presidents is not robust and goes away when you control the economic performance leading in to a president’s term.

Here’s Campbell:

Previous estimates did not properly take into account the lagged effects of the economy. Once lagged economic effects are taken into account, party differences in economic performance are shown to be the effects of economic conditions inherited from the previous president and not the consequence of real policy differences. Specifically, the economy was in recession when Republican presidents became responsible for the economy in each of the four post-1948 transitions from Democratic to Republican presidents. This was not the case for the transitions from Republicans to Democrats. When economic conditions leading into a year are taken into account, there are no presidential party differences with respect to growth, unemployment, or income inequality.

For example, using the quarterly change in GDP measure, the economy was in free fall in Fall 2008 but in recovery during the third and fourth quarters of 2009, so this counts as Obama coming in with a strong economy. (Campbell emphasizes that he is following the lead of Bartels and counting a president’s effect on the economy to not begin until year 2.)

It’s tricky. Bartels’s claims are not robust to changes in specifications, but Campbell’s conclusions aren’t completely stable either. Campbell finds one thing if he controls for previous year’s GNP growth but something else if he controls only for GNP growth in the 3rd and 4th quarter of the previous year. This is not to say Campbell is wrong but just to say that any atheoretical attempt to throw in lags can result in difficulty in interpretation.

I’m curious what Doug Hibbs thinks about all this; I don’t know why, but to me Hibbs exudes an air of authority on this topic, and I’d be inclined to take his thoughts on these matters seriously.

What struck me the most about Campbell’s paper was ultimately how consistent its findings are with Bartels’s claims. This perhaps shouldn’t be a surprise, given that they’re working with the same data, but it did surprise me because their political conclusions are so different.

Here’s the quick summary, which (I think) both Bartels and Campbell would agree with:

– On average, the economy did a lot better under Democratic than Republican presidents in the first two years of the term.

– On average, the economy did slightly better under Republican than Democratic presidents in years 3 and 4.

These two facts are consistent with the Hibbs/Bartels story (Democrats tend to start off by expanding the economy and pay the price later, while Republicans are more likely to start off with some fiscal or monetary discipline) and also consistent with Campbell’s story (Democratic presidents tend to come into office when the economy is doing OK, and Republicans are typically only elected when there are problems).

But the two stories have different implications regarding the finding of Hibbs, Rosenstone, and others that economic performance in the last years of a presidential term predicts election outcomes. Under the Bartels story, voters are myopically chasing short-term trends, whereas in Campbell’s version, voters are correctly picking up on the second derivative (that is, the trend in the change of the GNP from beginning to end of the term).

Consider everyone’s favorite example: Reagan’s first term, when the economy collapsed and then boomed. The voters (including Larry Bartels!) returned Reagan by a landslide in 1984: were they suckers for following a short-term trend or were they savvy judges of the second derivative?

I don’t have any handy summary here–I don’t see a way to declare a winner in the debate–but I wanted to summarize what seem to me to be the key points of agreement and disagreement in these very different perspectives on the same data.

One way to get leverage on this would be to study elections for governor and state economies. Lots of complications there, but maybe enough data to distinguish between the reacting-to-recent-trends and reacting-to-the-second-derivative stories.

P.S. See here for comments by Campbell.