On Feb. 14, 2024, close to 150 million Indonesians voted in the country’s fifth direct presidential election. Three candidates were on the ballot: Anies Baswedan, an academic with a PhD from the United States who was backed by Islamist groups; Prabowo Subianto, a former general under Suharto’s authoritarian regime and the candidate with the backing of the incumbent president; and Ganjar Pranowo, governor of the Central Java province – who was backed by the Democratic Indonesia of Struggle Party (PDI-Perjuangan), the party that once was the incumbent president’s home party.

The official results won’t be released until March. But initial counts suggest that Prabowo Subianto will win the election with 55% to 60% of the votes. How did a country that’s been free from the chains of authoritarianism for just 25 years decide to elect another strongman? At least two factors are at play: younger voters and the incumbent president’s ability to play kingmaker.

Younger voters had their say

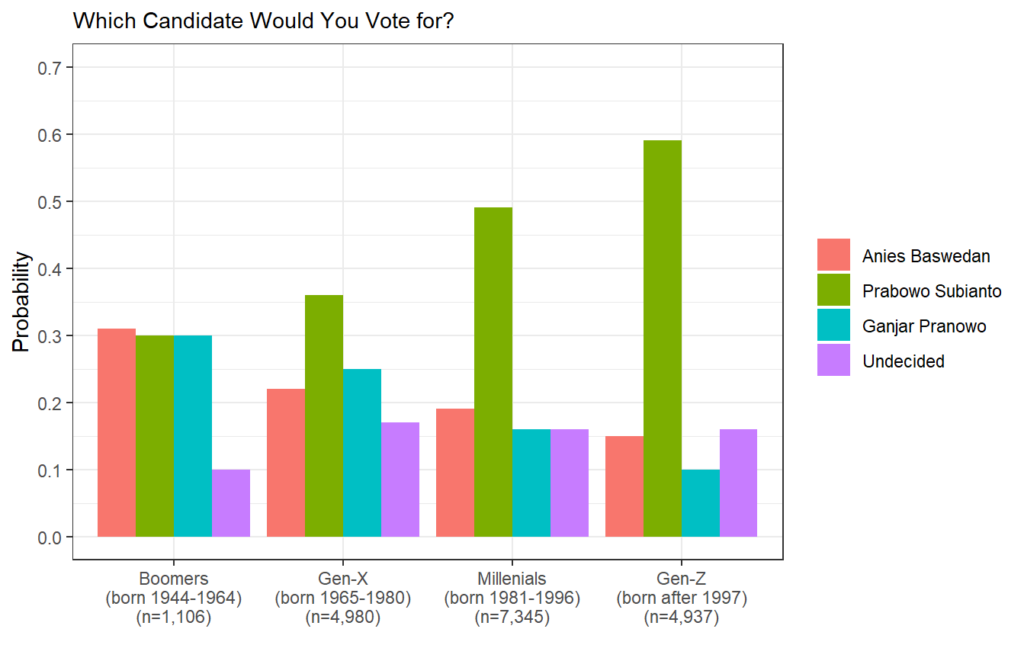

Younger voters accounted for the majority of the electorate in 2024. Data from the Indonesian Electoral Commission (KPU) indicated that 52% of the voters were below 40 years old and 31% were below 30.

Prabowo Subianto enjoyed a significant advantage among this age group. Preelection surveys showed that support for the former general was stronger among younger than older voters. The figure below, based on my analysis of preelection survey data, shows this pattern where Gen Z voters were much more likely to support Prabowo than voters in the older age groups. An exit poll on election day also revealed that about 66% of voters younger than 26 voted for Prabowo Subianto.

Indonesia’s transition to democracy started in 1998, when student demonstrations forced the dictator Suharto to resign after 32 years in power. This means that the oldest of these young voters was just about 15 years old when the transition happened. Most have spent their lives in a free, relatively democratic Indonesia.

A young electorate has important consequences. First, Indonesians’ collective memory of what happened in 1998 seems to have faded. Prabowo was an army general under Suharto, and also his son-in-law. In 1998, a committee of high-ranking officers dismissed him from military service for his alleged involvement in the kidnappings of pro-democracy activists, some of whom are still missing today.

Yet a preelection survey found that about 76% of Indonesian voters were not aware of these allegations. Most of the officers who fired Prabowo from the military even joined his campaign. Prabowo’s heaviest baggage, his human rights record and close ties with the late dictator, apparently was not even a decisive issue in the election.

Second, Suharto’s development policy – pursuing economic development as the top priority – seems to resonate with young Indonesians. Millions of these young voters are part of Indonesia’s “sandwich generation.” In the absence of a robust social security system, they remain sandwiched by the financial obligation to take care of their own welfare, the welfare of their children, and the welfare of their parents. Economic concerns were therefore a key consideration for many young voters.

A 2021 survey found that, among voters aged 17 to 21 years old, 59% agreed that economic development was more important than democracy. Among these voters, the majority (59%) disagreed that Indonesia would be better off returning to a Suharto-style authoritarian system. But that figure also suggests that 30% of respondents could not choose between an authoritarian system and the democratic system the country has pursued for over two decades. Thus, economic stability and development were perhaps more appealing to young voters than rather abstract principles of democracy.

The youth vote worked in tandem with an even more powerful electoral force: the popularity of the term-limited incumbent president Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi.

Jokowi emerged as a kingmaker

Jokowi started his political career as the mayor of Solo, a mid-size city of about 500,000 people at the heart of the Central Java province. His approachable, down-to-earth appearance and his policies on improving the city’s sanitation, transportation, tourism, and economy contributed to his popularity.

After winning a first five-year term in 2005, his second mayoral term was cut short when he entered and won the Jakarta gubernatorial election in 2012. His party, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-Perjuangan), was shopping for a vice-presidential candidate to run on the 2014 presidential ticket with the party’s matriarch Megawati Soekarnoputri.

Jokowi was the party’s most popular cadre – but had little national recognition. The party sought to change that by elevating Jokowi to a gubernatorial seat in the nation’s capital. PDI-Perjuangan worked together with the Greater Indonesia Party (Gerindra), Prabowo Subianto’s party, to help Jokowi win his gubernatorial seat and the national spotlight that followed.

Indonesia’s 2014 elections were polarizing

The 2014 elections were run in two stages. In April, a legislative election under a proportional representation system with multimember constituencies selected the next members of parliament. The electoral rules then specified that only a party or a coalition of parties with 25% of the popular vote or 20% of parliamentary seats could propose candidates for the presidential election in July 2014.

By 2014, it was clear that Jokowi had become more popular than his then-patron Megawati. PDI-Perjuangan had little choice but to put Jokowi on the top of the presidential ticket. His coalition amassed only 40% of the popular vote and 37% of the legislative seats.

His opponent? Prabowo Subianto, the leader of the Gerindra party, which had helped Jokowi win the Jakarta governor race. Prabowo’s coalition commanded 49% of the popular vote and 52% of the seats in the parliament.

It was, by most accounts, a polarizing election. Many expected Prabowo to defeat Jokowi in 2014, given his coalition’s larger vote share. But Jokowi won the presidency, with 53% of the votes. These election dynamics repeated in 2019 when Prabowo again challenged and lost to Jokowi, earning only 45% of the vote.

Jokowi pursued bold initiatives

Having won a second term and consolidated his ruling coalition, Jokowi was no longer shy about making bolder pushes for his policy agendas. He pressed ahead with a plan to move the country’s capital from Jakarta to a newly built city in Kalimantan (Borneo). He passed sweeping laws on jobs and on corruption and overhauled the criminal code law, all in the face of strong opposition from civil society organizations.

Jokowi’s boldest maneuver, and the one with the most significant political consequences, was bringing Prabowo Subianto in as defense minister in 2019. Jokowi’s relationship with Prabowo had only gotten warmer from that point, but remained as one between a president and his cabinet member. Nominally, Jokowi was still a PDI-Perjuangan cadre.

This changed in October 2023, when Jokowi gave a blessing for his son Gibran Rakabuming Raka to be Prabowo’s running mate. Even though Jokowi’s PDI-Perjuangan party had its own candidate – Ganjar Pranowo – it became clear that Jokowi was not toeing the party’s line and that the Prabowo ticket was his preferred choice.

With Jokowi enjoying approval ratings as high as 75%, this gave Prabowo a strong electoral boost. Polls documented an uptick in Prabowo’s electability soon after Jokowi’s son teamed up with him. Exit polls on election day revealed that more than 60% of respondents who said they were satisfied with Jokowi’s performance in office voted for Prabowo.

What is next for Indonesia?

The likelihood that a disgraced former general will be Indonesia’s next president has already raised concerns about the future of Indonesia’s democracy. But if Indonesia’s democracy were going to regress further, it would not be Prabowo’s own doing.

Ten years under Jokowi’s rule has shrunk civic space, reduced government accountability, weakened parliamentary oversight, and eroded democracy in Indonesia. In that sense, if Prabowo follows Jokowi’s developmentalist path, further democratic erosion would be a likely outcome.

The biggest post-election question, and the one with most significant consequences, is how the relationship between Jokowi and Prabowo will evolve after the transition. Jokowi surely supported Prabowo out of a belief, or a calculation, that the new regime would advance his policies and agendas. But beliefs are rarely good enough in politics.

Once he leaves office, Jokowi’s ability to influence Prabowo will weaken significantly. His son will be the vice president, but the vice presidency is not powerful. And the break-up with PDI-Perjuangan leaves Jokowi without a party. Unless he manages to coopt a political party to do his bidding, he will not be able to use the legislature to control Prabowo and hold him accountable. Jokowi now becomes a former president without military credentials. In a country where the military has political clout, this is a serious disadvantage.

The prospect of a renewed rivalry between Prabowo and Jokowi could now open up larger questions about Indonesia’s democracy.

The 2014 election, when Jokowi and Prabowo faced off for the first time, proved extremely divisive; and that was when both figures were out of the circle of power. A new rivalry between a popular former president and a new president with control of the military, should the two go separate ways, would bring great uncertainties – and new potential strains on Indonesia’s democracy.

Nathanael Gratias Sumaktoyo (@nathanaeldotid) is assistant professor of political science at the National University of Singapore.