In early 2024, the U.S. conducted multiple waves of airstrikes against Houthi forces that were targeting naval and commercial shipping around Yemen. The U.S. responded similarly to the Jan. 28 drone attack in Jordan that killed three U.S. service members, striking Iranian-backed militias in Syria and Iraq. In early February, a U.S. drone killed a senior commander of one such militia in Baghdad.

The conflict seems likely to continue: As recently as Valentine’s Day, U.S. Central Command announced it had destroyed a Houthi cruise missile on a launch pad in Yemen.

With such broad military operations, will war spread in the region? And – to keep alive my ongoing (nay, endless) series on this topic – does the president have the constitutional power to conduct these operations? “Our response began today,” Pres. Joe Biden said on Feb. 2. “It will continue at times and places of our choosing.” But is that choice entirely presidential? – or does Congress have a say? Let’s explore.

War powers in the Constitution

Constitutional scholar Edward Corwin famously said the U.S. Constitution sets up an “invitation to struggle” for “the privilege of directing American foreign policy.” The war powers are a case in point. For instance, Article I of the Constitution allocates Congress the power to declare war, to raise and regulate and support the armed forces, to “define and punish” piracy and “Offenses against the Law of Nations,” and to call out the militia if needed to “repel Invasions.” Article II vests “the executive power” in the president and makes the president commander in chief of the armed forces, including any federalized militia (the National Guard, these days).

The debates over the Constitution, well into early U.S. history, document that this division of authority is intentional, designed to inoculate the new government against the prerogative powers over the military attributed to the British monarch. The debate did make clear that the framers expected the president would defend against “sudden attacks”; as Roger Sherman put it, “the executive should be able to repel and not to commence war.”

In Federalist #69, Alexander Hamilton noted that being commander in chief was nice, but without Congress having funded an army and declared war there would be nothing much to command; such “authority would [thus] be nominally the same with that of the king of Great Britain, but in substance much inferior to it.” James Wilson – like Hamilton, an advocate for a strong presidency in the Constitution – reassured the Pennsylvania state ratifying convention that “this system will not hurry us into war; it is calculated to guard against it. It will not be in the power of a single man, or a single body of men, to involve us in such distress; for the important power of declaring war is vested in the legislature at large.”

Still, presidents have accepted the invitation to struggle and largely won it – indeed, sometimes with Congress’s help. After World War II, for instance, presidents took advantage of being commander in chief of huge standing armies to, well, command them. World War II was also the last time the U.S. declared war, despite its seemingly perpetual use of force abroad since then.

The War Powers Resolution

As the Vietnam War corroded any national consensus it once had, pushback against the growth of presidential war powers ensued. Congress had given Lyndon Johnson a so-called blank check with the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. But over time suspicions grew about whether the North Vietnamese attack on a U.S. destroyer that justified the resolution had actually occurred. Promises that U.S. forces would soon win the war toppled over the edge of a gaping “credibility gap.“ That fissure only grew wider as Richard Nixon secretly expanded the war into neighboring (and neutral) Cambodia and ordered the massive 1972 “Christmas bombing” of Hanoi soon after his administration’s promise that “peace is at hand.”

In 1973, legislators overrode Nixon’s veto to enact the War Powers Resolution (WPR). The WPR was meant to ensure the “collective judgment of both the Congress and the President” would inform decisions concerning “the introduction of United States Armed Forces into hostilities, or into situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances.”

The new requirements to go to war

The WPR had three general provisions. First, the president was to consult with Congress “in every possible instance” before using force. Second, presidents were given authority to use force only when there was 1) a declaration of war; 2) a specific statutory authorization; or 3) “a national emergency created by attack upon the United States, its territories or possessions, or its armed forces.”

But, third, even in the cases of self-defense contemplated by the third category, Congress wrote in a sunset provision: Armed forces had to be withdrawn from action immediately if Congress ordered it, or after no more than 90 days, unless legislators had approved the use of force in the meantime.

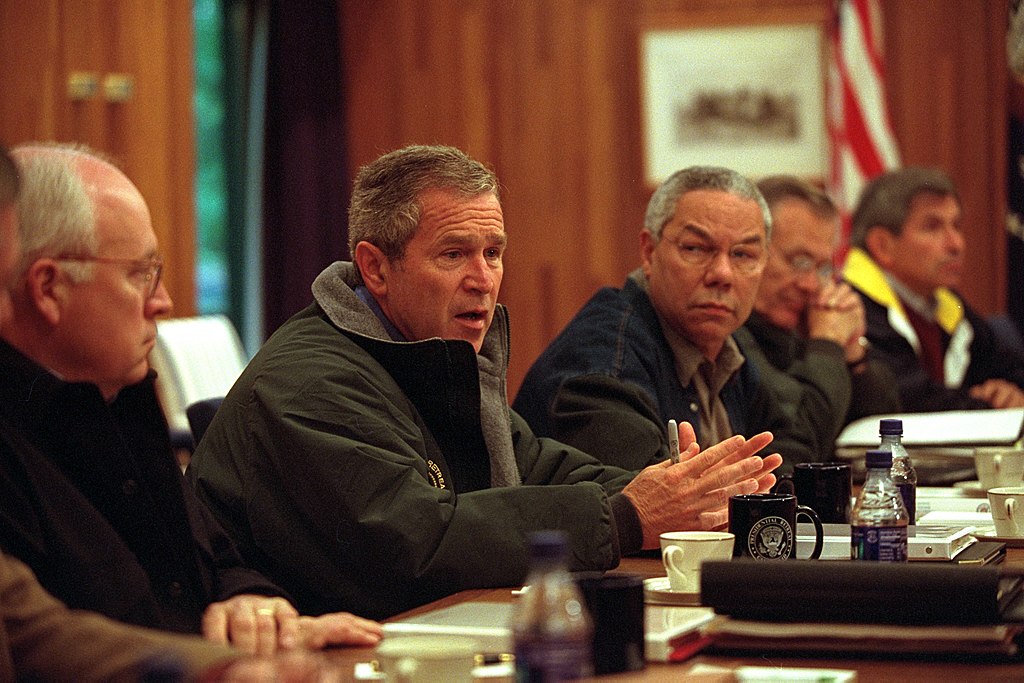

The effect of the WPR has been far smaller than its authors intended. From Nixon on, U.S. presidents have adopted the default position that the law represents an unconstitutional infringement on their authority. As discussed below, since the WPR passed, presidents have asked for congressional authorization for large-scale military action. For instance, both presidents Bush did so for their respective wars in Iraq. But they claimed they didn’t actually need to do so. This suggests the WPR’s impact may be on the political as much as the legal dynamics linked to going to war.

More commonly, presidents gesture at compliance but take advantage of the resolution’s vague, even contradictory provisions to undermine it. Prior consultation in “every possible instance”? Well, presidents have proven adept at finding most such instances simply impossible. They have also tended to redefine “consultation” as “notification,” maybe in advance but, more often, not. Even Gerald Ford, the only president to date to formally invoke the WPR, met with members of Congress about his politically successful but militarily dubious action in Cambodia only after the fact.

Since that first Ford report in 1975, presidents have framed their notifications to Congress as “consistent with” the resolution – not “pursuant to” it. Joe Biden’s Feb. 4 letter to Congress, for instance, makes that point clearly. That distinction matters because the WPR’s 90-day clock begins counting down only when presidents report to Congress under the auspices of the resolution (unless Congress itself starts it ticking, which has happened only once, when Reagan stationed troops in Lebanon in 1983).

So it’s still not easy for Congress to rein the president in. It doesn’t help that, in 1983, the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional the original WPR mechanism for legislative rejection of presidential action, a concurrent resolution – effective without White House say-so. Now congressional opponents of military action need to muster a two-thirds majority in each chamber to overturn the near-certain presidential veto of a joint resolution invoking the WPR. That is a difficult task. In 2019, for example, Congress voted to end U.S. military involvement in Yemen’s civil war but could not override Donald Trump’s veto.

Presidents have ready rationales for war

Presidential uses of force without statutory authorization or a declaration of war have often invoked broad notions of self-defense to fit their action into category 3 above. That includes Jimmy Carter’s (failed) rescue attempt of the American hostages in Iran in 1980 and Bill Clinton’s 1998 missile strikes retaliating for al-Qaeda’s bombings of U.S. embassies in Africa.

But what counts as an “attack upon the United States”? The phrase has led to broad interpretation. In 1989, George H.W. Bush said that Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega’s “reckless threats and attacks upon Americans in Panama” were creating “an imminent danger to the 35,000 American citizens” there, providing a key rationale for invasion. In 1983, Ronald Reagan publicly justified the U.S. invasion of Grenada along similar lines, claiming “American lives are at stake.”

Even more broadly, as Harvard law professor Jack Goldsmith recently noted, the executive branch view of self-defense extends to what we might call “anticipatory self-defense” and indeed to the “collective self-defense of partnered forces,” meaning simply any other entity the Department of Defense decides to partner with.

Presidents also frequently invoke treaties, multilateral support, and/or a cause of action endorsed by the international community, normally with a humanitarian component. Even Reagan was careful to stress that the U.S. had been invited to respond in Grenada, that it was doing so in concert with other nations in the region with fewer battleships handy, and that “this collective action has been forced on us by events that have no precedent in the eastern Caribbean and no place in any civilized society.”

Likewise in Somalia (1992), Kosovo (1999), and Libya (2011), one could cite both humanitarian concerns and treaty obligations – for instance, to the United Nations, NATO, or both. The WPR specifically rules out inferring authority to use force from such obligations. But such claims are good optics, and help bolster domestic political arguments.

Presidential self-dealing

There are at least two other ways for presidents to sidestep the WPR. Both involve expressing fidelity to its authority while ignoring its constraints.

First, presidents can claim they are complying with the WPR because they have statutory authorization to act; see category 2, above. Sometimes this is clearly true: The 2003 invasion of Iraq came after Congress delegated that power to George W. Bush in October 2002. But more frequently presidents rely on a broad stretch of prior language – most often the 2001 Authorization for Military Force (AUMF), trying to trace any threat back through what might be called “six degrees of al-Qaeda.”

The 2001 AUMF, passed just a few days after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks on U.S. soil, says:

… the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations, or persons.

Despite its general breadth, the text is specific to the 9/11 attacks. It clearly authorized the attacks on the Taliban and al-Qaeda that soon followed. But as the New York Times’ Charlie Savage gently put it, “distance has grown between the text of the 2001 authorization and the combat waged in its name.”

Since 2001, the war against al-Qaeda has spread far beyond Afghanistan, and to many groups that are not al-Qaeda but that have been defined as “associated” or successor forces to that group. For instance, the U.S. has brandished the 2001 AUMF’s authority to support its operations versus the self-proclaimed Islamic State (ISIS), and even into several African nations, largely against al-Shabab. Presidents have also used the 2002 Iraq AUMF to justify the use of force in and around Iraq, well after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s regime it authorized.

Critics suggest, as Sen. Ben Cardin (D-Md.) put it in 2017, that past AUMFs have become “mere authorities of convenience for presidents to conduct military activities anywhere in the world.” In 2021, the House voted to repeal the 2002 Iraq AUMF; in 2023, so did the Senate (senators added the one from 1991, for good measure). But neither measure passed the other chamber. Part of the problem is in finding a balance between those in Congress who want to simply empower the president and those who want to limit his autonomy. But a cynic – or even my Good Authority colleague Elizabeth Saunders; see her fourth point – might argue that legislators find the status quo politically useful. Here’s why: They can complain loudly about presidential action without taking responsibility.

Hostile to “hostilities”

Second, presidents have argued that the WPR is simply inapplicable, because their uses of force do not constitute “hostilities” under the law and thus don’t activate its requirements in the first place. Brian Egan and Tess Bridgeman at Just Security lay out the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) opinions holding that Article II gives the president the power to initiate the use of military force when there is an important “national interest” to do so (as defined by the president) and when the force does not constitute “war in the Constitutional sense.” OLC argues that “military operations will likely rise to the level of a war only when characterized by ‘prolonged and substantial military engagements, typically involving exposure of U.S. military personnel to significant risk over a substantial period.’”

As Barack Obama said in 2011, the only “kinds of commitments” that would make the WPR relevant were those on the scale of the Vietnam War – “in which we had half-a-million soldiers there, tens of thousands of lives lost, hundreds of billions of dollars spent.”

That redefinition allowed the Obama administration to claim that military operations in Libya did not count as “hostilities” for War Powers Resolution purposes. The Trump administration in turn claimed the same was true of its 2017 and 2018 airstrikes against Syria in response to the Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons. Indeed, in a (still heavily redacted) 2020 opinion justifying the 2020 assassination of Iranian general Qasem Soleimani, the OLC implied that even a conflict’s “anticipated nature, scope, and duration” doesn’t matter when the U.S. is defending itself. This seems to circle back to the broadest arguments for the president’s power of even preemptive self-defense.

“Fact-intensive” calculations

As I noted in an earlier post, the current responses to Houthi or militia attacks seem to fit comfortably within the WPR category of self-defense. But even in those cases, the 90-day WPR clock is ticking, and U.S. strikes run the risk of becoming more preemptive than reactive. As Goldsmith notes, the Biden administration’s calculations about where military action fits within legal doctrine will depend on the specific actions taken. These calculations are necessarily “fact-intensive.”

It’s worth noting, though, that in larger cases – even if not on the scale of another “Vietnam,” by Obama’s definition – presidents have indeed sought authorization to move forward. The first Gulf War in 1991, the Afghanistan war starting in 2001, and the Iraq war in 2003 all received congressional sanction at presidential request – even though the presidents involved never conceded they needed congressional authorization to act. In 1992, after the fact, George H.W. Bush said that “I didn’t have to get permission from some old goat in Congress to kick Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait.”

This approach suggests that presidents see it as good politics to have a clear domestic mandate, especially if they sense such authorization will be easy to obtain. It might be wise, too, to have a potential partner in any future failures – even regarding failures to act in the first place. In 2013, Obama rather surprisingly sought approval for airstrikes against Syria even as he claimed to “have the authority to carry out this military action without specific congressional authorization.” It was “the right thing to do for our democracy,” he added. But perhaps it was also the right thing to share the blame as well, when Congress refused to vote.

The boundaries here are ultimately up to Congress to enforce – and there are many proposals for hardening legislators’ collective spine. But new limits are easier to propose than implement, especially when an airstrike may take closer to 90 minutes than 90 days. Even for longer-term operations presidents can set the agenda, forcing a skeptical Congress to maneuver around the fact of U.S. forces in the field: The power of the purse has long run up against the political difficulty of defunding American troops in harm’s way. It doesn’t help that lawmakers’ opinions on presidential power frequently fall along partisan lines – presidents of one’s own party seem to magically accrue additional constitutional authority.

In the end, then, the barriers to Congress taking up its end of the “invitation to struggle” are less constitutional than practical and political. But that has not made dismantling them less daunting.

Related Good Authority posts:

- Andrew Rudalevige, “Biden may be getting rid of the Authorizations for the Use of Military Force. That deserves a ‘Whoa.’“ From March 2021, this post responded to news that Biden might endorse repealing the various existing AUMFs.

- Andrew Rudalevige, “Does Trump need Congress’s authority to go to war with Iran?” This January 2020 post responded to a Pentagon announcement that it would deploy 3,500 more U.S. troops to the Middle East, rousing fears of a broader war.

- Andrew Rudalevige, “When did Congress authorize fighting in Niger? That’s an excellent question.“ This September 2017 piece suggested that Congress might wish to consider passing a new AUMF.

- Andrew Rudalevige, “Is the war against the Islamic State illegal? A new lawsuit should prompt Congress to decide.“ This May 2016 piece looked at an unusual lawsuit arguing against Obama’s use of the 2001 AUMF.

- Andrew Rudalevige, “Six degrees of al-Qaeda.“ This September 2014 piece examined how the Obama administration was tracing its authority to pursue military action against the Islamic State through the AUMF against al-Qaeda.

For further reading:

- Congressional Research Service, The War Powers Resolution: Concepts and Practice (2018).

- Tanisha M. Fazal, Wars of Law: Unintended Consequences in the Regulation of Armed Conflict (Cornell University Press, 2018).

- Louis Fisher, Congressional Abdication in War and Spending (Texas A&M Press, 2000).

- Jack Goldsmith, “The Middle East and the president’s sweeping power over self-defense,” Lawfare (October 23, 2023).

- New York University School of Law Reiss Center on Law and Security, War Powers Resolution Reporting Project.

- Andrew Rudalevige, The New Imperial Presidency (University of Michigan Press, 2006).

- Andrew Rudalevige, “Authorizing Force, Twenty Years after 9/11,” Bipartisan Policy Review (2022).

- Mariah Zeisberg, War Powers: The Politics of Constitutional Authority (Princeton University Press, 2013).

Last updated: February 20, 2024

Do you have a proposal for an explainer, either one you want to read or one you would write? Send us your suggestions or proposals using this form! Please note that we will review all proposals but not all will be published. Anyone can request an explainer; potential authors must hold a PhD in political science.