Modern globalization, dependent on bulk shipping via open seas, is under fire – the real live kind. Most recently, the spillover of the Israel-Hamas conflict has emboldened Houthi rebels from Yemen to attack shipping in the Red Sea. Shipping companies are coping with major new costs, as insuring their vessels in dangerous waters becomes more and more difficult.

While the Red Sea developments – and their potential to escalate – are big news, it’s not the first time that territorial or geopolitical conflicts have spilled into the seas. We are watching in real time as other major powers and their proxies challenge the West’s dominance in sea power – threatening the maritime commerce that makes the global economy run. And what’s happening today won’t be the last time we see this type of threat.

What’s going on in the Red Sea is significant

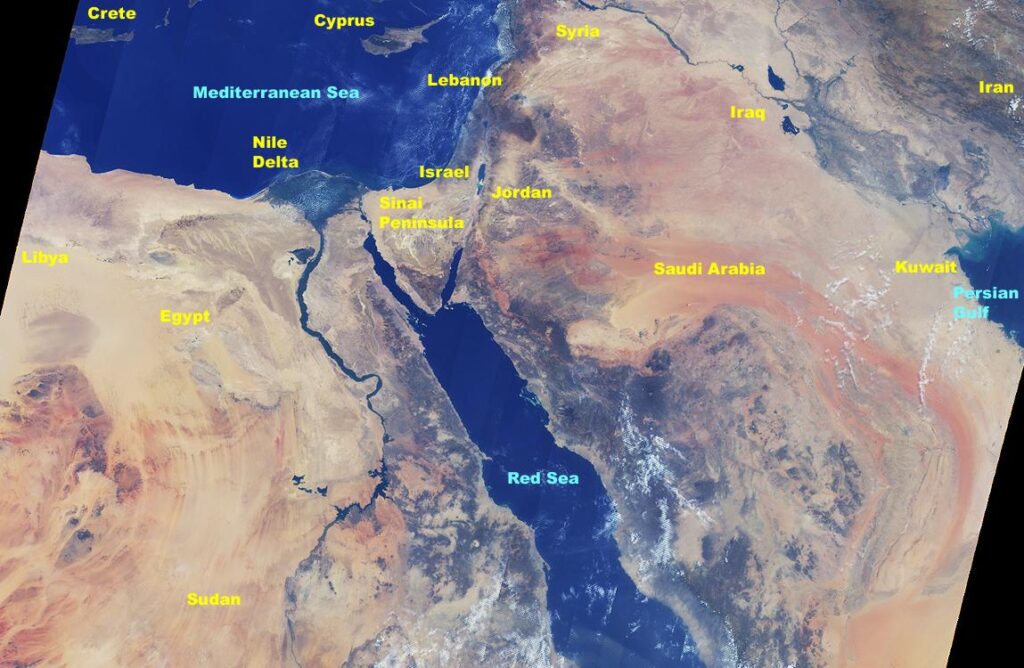

At its core, the current Red Sea crisis is a spillover of the Israel-Hamas war. Houthi rebels in Yemen are taking advantage of the regional disruption, and have garnered world attention with attacks on commercial shipping.

The Houthis also have the U.S. military’s attention. On January 9, 2024, F-18s launched from the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, together with the USS Laboon, an Arleigh Burke-class destroyer patrolling in the Red Sea, two other American ships, and the British HMS Diamond, shot down a salvo of more than 20 drones and missiles launched from Yemen by Houthi forces. It was the 26th attack since November 23, when the USS Hudney and later the USS Mason and the USS Carney began shooting down salvos of missiles and drones launched against commercial ships in the area of the Bab El Mandab – a strait at the south end of the Red Sea known as the “Gate of Tears.”

In the intervening weeks, the U.S. government has been working – with at best partial success – to assemble a naval escort coalition to defend shipping. Most recently, the Indian Navy officially joined the fray, though not, technically, the coalition. Indian naval vessels will escort Indian-flagged vessels through these once-again contested waters. The U.S. and U.K. issued warnings of a near-term shift from defensive moves to direct strikes against the Houthis.

The Red Sea and Suez Canal are vital routes

By itself, the ongoing Red Sea crisis is significant. The Suez Canal, at the northern end of the sea, is a vital artery of trade between Asia and Europe. Nearly 30% of the world’s container ships and 12% of global oil and gas supplies flow across this shipping route. Disrupting this volume of trade for more than a couple of weeks is going to cause serious disruption to the global economy.

Already the cost of international shipping has spiked by 173%. That’s not the bad part, though. Longer shipping times – as major carriers re-route around the Cape of Good Hope – will cause huge knock-on effects on the supply of ships, containers, and crew. These disruptions, in turn, will create logjams and shortages in just-in-time globalized supply chains. And that’s to say nothing of the cost of keeping several destroyers, two aircraft carriers, escort ships, and merchant marine logistics vessels active in the Red Sea and Strait of Hormuz for however long is necessary (likely months).

It’s possible that direct strikes against Houthi targets will deter further attacks. But the history of Cold War proxy fights tells us that threats of attack may be less effective when a larger power (in this case, Iran) supplies weaponry and political support to the proxy forces carrying out the attacks. And striking Houthi targets carries the risk of escalating the conflict further.

Russia’s aggression has also spilled into the seas

The wider problem is that the Red Sea is not the only body of water where geopolitical contestation is threatening good order and commerce at sea. Sea flows are the lifeblood of the global economy, carrying 60% of all food stocks, roughly two-thirds of the world’s supply of oil and gas, and 90% of all commercial trade.

In the nearby Straits of Hormuz, Iran is threatening to widen the conflict, using its large fleet of small attack vessels and/or missiles and drones, to disrupt commercial shipping in that even more vital sea lane.

In Europe, the Russian re-invasion of Ukraine in 2022 quickly spilled into the Black Sea, disrupting critical flows of food and fertilizer to global markets.

And Moscow is also threatening globalization’s most essential and most vulnerable networks on the seabed itself. Russian submarines have been spotted in Irish waters near a huge concentration of undersea financial cables that connect the New York and London stock exchanges – the jugular of the global financial system.

A Russian nuclear-powered research vessel and an accompanying Chinese commercial ship were trailed as they sailed over Norwegian seabed pipelines that carry natural gas to Europe – the very pipelines that have allowed Europe to eschew Russian gas flows. The same pair of ships reportedly damaged both an energy pipeline and a data cable linking Estonia to Finland and Sweden, respectively. And Russia’s quiet nuclear submarines are once again patrolling extensively in the north Atlantic and near-Arctic waters.

U.S.-China competition is happening at sea, too

The United States has long defined freedom of navigation and protection of the sea lanes of communication as a central strategic objective, including in the Pacific. But China’s capacity to challenge or disrupt this freedom is growing rapidly. In the past five years, China has launched a greater tonnage of high-quality naval vessels than the U.S., Australia, Japan, and South Korea combined.

This rapidly growing PLA Navy has been busy flexing its new muscles in the west Philippine Sea and the South China Sea. Expansive exercises in the Taiwan Strait, aggressive lawfare over the status of that body of water, harassment of Philippine coast guard vessels, and the largest naval build-up since the U.S. Navy’s surge after Pearl Harbor: These are all signs of growing tensions in the world’s most economically crucial waterways.

The West is struggling to keep up

These developments have revealed important limits in Western unity and capacity. The U.S. launch of Operation Prosperity Guardian to address the Houthi threat in the Red Sea was an expansion of a mission component of the preexisting multinational Combined Maritime Forces, headquartered in Bahrain.

Initially, the new operation saw an impressive list of contributors. But within days it became clear that some countries were contributing only a handful of staff officers, while others were sending ships – but not to join the combined force. And other countries balked at participating. To date, only the U.S., the U.K., France, Japan, and India have taken action to defend shipping in the Red Sea – and the large bulk of actions have been carried out by U.S. forces.

On a more positive note, in the same period, ten navies agreed to join forces to protect northern Europe’s critical undersea infrastructure from Russian (and potentially Chinese) damage. And countries like the U.K. have recapitalized their navies to a certain degree, at least from a post-Cold War low. The U.K., France, Canada, and Australia, for instance, have sent aircraft carriers or cruisers to patrol the South China Sea alongside U.S. Navy assets.

Western navies are stretched thin

The U.K. faces particular strain trying to contribute simultaneously in the Pacific and the Middle East, and its once-important submarine and anti-submarine capacities have eroded to minimal levels. France suffers from similar capacity constraints, while Germany is struggling to provide the kind of naval leadership its neighbors hope it could provide in the Baltic region. Asked to contribute to the Red Sea operation, Germany is struggling to find options.

The problems are not just in European navies. The U.S., long accustomed to having unrivaled blue-water naval dominance, is already stretched thin. With half of the U.S. Navy’s active submarines deployed to northern Europe to check the Russian fleet, two aircraft carriers and several destroyers in the Middle East, patrols in the Mediterranean, and a watchful eye on the Arctic, the Navy has plenty to keep it busy.

And all this activity pulls U.S. capacity away from what the Pentagon considers the biggest task: deterring China at sea. That the U.S. has to do that at a distance of 8,000 miles from America’s rear bases on the West Coast adds to the challenge and strain. Should tensions escalate in the Western Pacific, threatening both U.S. allies and globalization’s most important waterways, Western capacity to defend those seas will be stretched beyond breaking point.

The West can’t afford to lose control of the seas. But it’s going to need a lot more sea power to keep it.

Bruce Jones is a senior fellow in the Brookings Institution’s Center for Security, Strategy, and Technology, as well as their Center for East Asia Policy. He is the author of “To Rule the Waves: How Control of the World’s Oceans Shapes the Fate of the Superpowers” (Scribner, 2022).