Republicans this month charged that Democrats were exploiting Senate rules to delay confirmation of President Trump’s executive and judicial nominees. In return, egged on by an impatient president, Senate Republicans “went nuclear,” using a parliamentary routine to limit the amount of floor debate allowed before a final confirmation vote for lower-level executive and judicial nominees.

The Senate has 134 Trump nominees ready to consider; yet another 140 vacancies still need to be filled. Republicans argued that cutting back what’s called “post-cloture debate” would speed up confirmations.

But the reforms probably won’t speed things up much. Here’s why.

The road to confirmation

Confirming a presidential appointee involves several steps. First, presidential administrations identify and vet candidates. A president then submits nominations to the Senate, which refers them to committees, which review candidates’ credentials, backgrounds and qualifications.

If the committee approves — called “reporting” the nomination — it waits on the Senate’s Executive Calendar until the majority leader moves to consider it on the Senate floor. If a nomination dies in committee, a president typically withdraws it rather than forcing the Senate to vote to reject it.

If the majority leader cannot secure the consent of all 100 senators to schedule a confirmation vote, the leader typically files cloture on the nomination. Since Democrats went nuclear themselves in 2013, invoking cloture and limit debate on a nominee takes only a simple majority. And until the Senate went nuclear this month, the Senate could still debate the nomination for another 30 hours before the confirmation vote. The GOP’s most recent use of the nuclear option limited “post-cloture” debate to two hours.

Are Trump’s judicial nominees really being confirmed at a ‘record pace’? The answer is complicated.

This process has several bottlenecks

Our research, using our White House Transition Project’s records for the last six presidents, finds that the Senate has taken longer to move Trump’s nominees to a confirmation vote than with previous presidents.

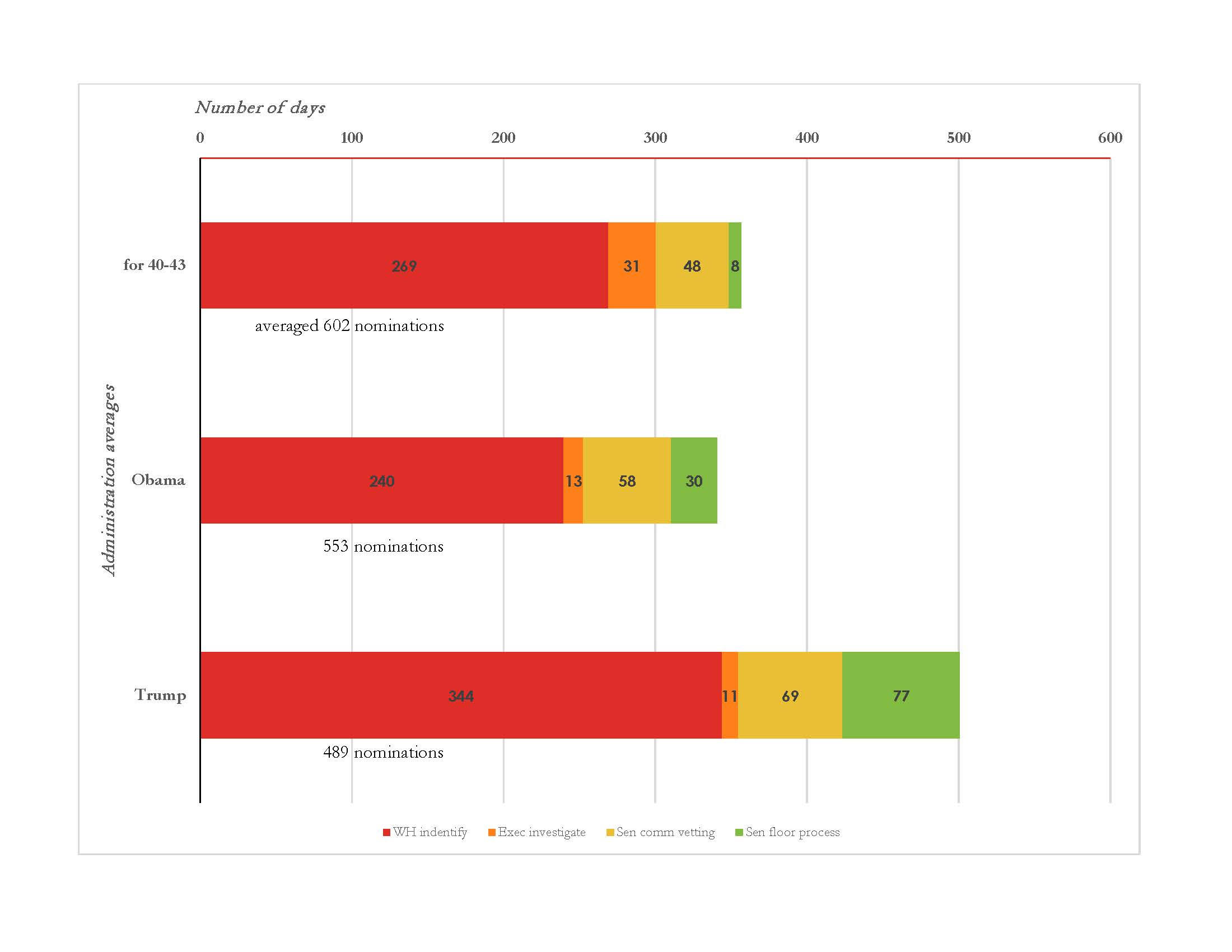

But as you can see in the figure below, Trump has taken longer to nominate candidates: 355 days on average for each one. He takes longer to nominate for low-level appointments (371) and less time to nominate district court judges (320). By comparison, Barack Obama took 253, while previous presidents averaged 300. The executive stage of nominations always take longer than any other and is the most severe bottleneck in the process.

Trump’s nominations have spent on average 69 days in committee — longer than the 58 days for Obama’s nominations.

Then Trump’s nominations wait an average of 77 days to the final confirmation vote, longer than the month it took for Obama’s nominations.

Low-level appointments and district court judges have waited the longest. This might be because Senate Democrats slow them down. But Republicans run the committees — and they’ve taken far longer than average to act on Trump’s nominees, too. Even the majority appears to find the president’s nominees more problematic than normal.

John Bolton’s appointment reveals this much bigger problem.

Will the new Senate change speed things up?

It’s true that debate after cloture has taken unusually long for Trump’s low-level and district court nominees.

Previous presidents’ nominees waited an average of eight days for a confirmation vote, after presidents took an average of 300 days to identify a nominee and committees took 48 days to review them. That’s roughly how long it’s taken the Senate to handle Trump’s non-district court judges and high-level appointments. But low-level appointments and district court judges are waiting an average of 114 days, an abnormally long time.

The rule change might speed things up at that stage. But the two greatest bottlenecks will still come at the White House and in committee.

So what’s causing that slowdown?

Several factors are behind these longer waits, including poor planning and underqualified or controversial nominees.

Just three days after his election, Trump fired his transition team and trashed its plans. That cost Trump that early window when new presidents traditionally use to staff up. The longer it takes an administration to nominate candidates, the longer the Senate takes to approve them.

That’s because the Senate tends to prioritize nominations in an administration’s early months, before it gets busy with legislation. Once a Senate majority takes up its legislative agenda, however, appointments take a back seat and can become bargaining chips. Senators from both parties can hold up otherwise uncontroversial nominees, taking them hostage for concessions on unrelated matters. That’s what happened after Trump’s late start: reviewing and approving appointments took a back seat to tax legislation, the effort to repeal Obamacare, fights over funding the border wall and the government shutdown.

What’s more, poor planning often results in underqualified nominees who face an uphill battle in the Senate. A number of Trump’s nominees lacked credentials or had troublesome track records or personal and financial indiscretions. For example, when Trump announced that he intended to nominate Herman Cain to the Federal Reserve Board, GOP senators pushed back, given past allegations of sexual misconduct.

Even majority parties slow-walk controversial nominees. That’s what happened with Barry Myers, nominated to head the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in October 2017. The committee took only two months to report the nomination — but for more than a year the majority leader has been considering how to deal with Myers’s conflicts of interest and his company’s settlement of a 2017 lawsuit about large-scale sexual harassment under his leadership.

Poor vetting can leave the president’s party in a tight spot unless the White House withdraws the damaged nomination. So far, Trump has withdrawn a record 40 announced or forwarded nominations, including Cain’s, 74 percent more than either Obama or George W. Bush. That suggests senators have found an unusual number of Trump’s nominations problematic.

Three reasons you should be startled by how the Senate rebuked Trump

Limiting post-cloture debate may speed up the confirmation process slightly, especially for conservative judges for the federal trial courts. But it’s unlikely to measurably quicken the process so long as the parties differ over nominees, and the Trump administration drags its feet in selecting qualified nominees.

Heather Ba is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Missouri.

Terry Sullivan is executive director of the White House Transition Project.