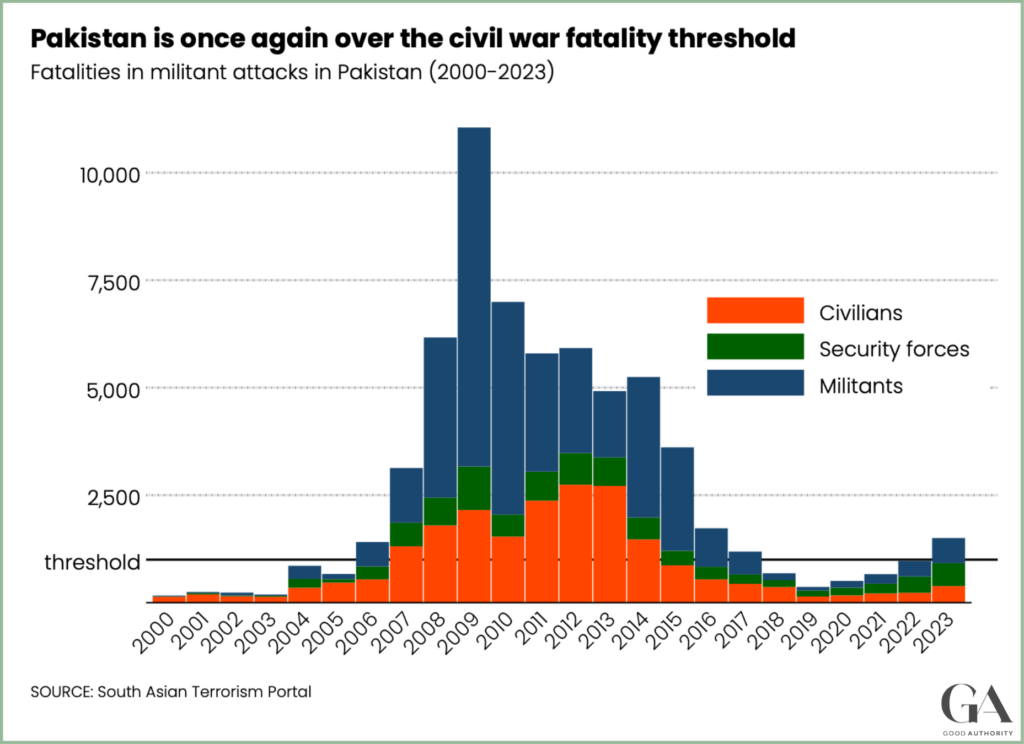

One of the many grim trends of 2023 was the rapidly increasing violence in Pakistan. The number of people killed in terrorist and militant violence in Pakistan increased by more than 50 percent last year, rising to 1,502. That figure reflects data collected by the Institute for Conflict Management and compiled on its widely referenced South Asia Terrorism Portal.

While definitions vary, more than 1,000 conflict-linked deaths in a year is a threshold political scientists use to delineate situations of “civil war” from other lower-intensity forms of conflict. The current violence in Pakistan has already crossed this threshold. The concern now is that the violence will not plateau at this level, but will continue to increase rapidly.

Pakistan’s complex ties with Afghanistan

Of course, terrorism and political violence in Pakistan is not new – but this is a departure from the relative calm of the past few years. In the decade after 9/11, Pakistan suffered a civil war as Islamist militants and terrorists attacked a Pakistani government that they believed was complicit in the U.S. occupation of Afghanistan. Pakistan’s role in Afghanistan was complicated. The country provided support to international forces that had ousted the Afghan Taliban, even as it maintained ties to the Taliban members who found safe haven in Pakistan.

Pakistan’s hedging with the Afghan Taliban did not spare it from severe bloodshed, however. In the worst year of violence, Pakistan lost over 11,000 people to terrorist and militant attacks in 2009. Though multifaceted, much of this violence could be traced back to the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP), an Islamist terrorist group with extensive ties to the Afghan Taliban and historically close ties with Al Qaeda. A multiyear Pakistan military campaign – especially Operation Zarb-e-Azb, which began in 2014 – complemented by U.S. drone strikes weakened the TTP by the end of the 2010s.

Why now? What has changed?

What explains this worsening situation since 2019?

Some observers point to a deterioration in civil-military relations in Pakistan. This then complicates counterterror and counterinsurgent efforts that depend on joint civilian and military efforts. Recent political science research spanning 1990 to 2007 found that across 165 countries, civil-military friction was associated with a marked increase in domestic terror attacks. Pakistan’s recent experience might be sadly consistent with that pattern.

A related accusation is that policymakers are distracted by political discord. The major Pakistani English-language newspaper, Dawn, editorialized on January 3, “While Pakistan’s leadership remains almost exclusively occupied in political machinations, militants and terrorist outfits have been spreading their vicious tentacles.”

Others attribute Pakistan’s troubles today to the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021. Afghan counterinsurgency efforts were hampered for two decades by the Afghan Taliban’s use of Pakistan as a safe haven. And now Pakistan’s own efforts to quell non-state violence are endangered by a safe haven in Afghanistan for militants. Just as Kabul demanded Pakistan take serious action against anti-Afghan militants in the 2000s and 2010s, now Islamabad demands Afghanistan take serious action against anti-Pakistan militants.

Pakistan’s friends and foes are watching warily

Given Pakistan’s past support for terrorist groups, many observers have been quick to highlight the irony of the current violence – even seeing it as punishment for past sins. In India, a neighbor with a long adversarial relationship with Pakistan, some observers called it “karma.” This would appear be “blowback,” proposed other commenters. “Pakistan might soon regret its win in Afghanistan,” argued Anchal Vohra in a September 2021 Foreign Policy article.

While rival India may believe a Pakistan distracted by domestic instability is safer for Indian interests, the United States and other international powers may calculate differently. The U.S.-led international intervention in Afghanistan was always interlinked with U.S. concerns about the stability of Pakistan. As incoming vice president in early 2009, Joe Biden reportedly went so far as to tell Afghan President Hamid Karzai that Pakistan was “fifty times more important than Afghanistan for the United States.”

Concerns about the nuclear arsenal

In addition to the terrorism threat, U.S. worries with Pakistani instability always were closely linked to concerns about the security of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal. As the Obama administration deliberated repeatedly about withdrawal from Afghanistan, U.S. officials worried that doing so would endanger the U.S. ability to monitor and help protect the Pakistan arsenal.

Pakistan’s nuclear force was small in 2001, as Pakistan had only tested nuclear weapons for the first time in 1998. But this arsenal would grow over the next decade – numbering perhaps 170 weapons today, according to outside experts, with an estimated stockpile of plutonium and highly enriched uranium for many more weapons. These weapons, combined with Pakistan’s background instability, led President Biden to opine in October 2022 that Pakistan was “maybe one of the most dangerous nations in the world” because it had “nuclear weapons without any cohesion.”

So far, during this present period of turmoil, the international community has been content with bolstering the Pakistani economy to buy time for its civil-military leadership to restore stability and hold previously delayed national elections. While hesitant to be pulled into Pakistan’s problems, outside powers have often feared instability in nuclear states and worked to prop up even troublesome governments under strain.

Whether 2023 proves to be a tragic but transitory uptick in violence is not just Pakistan’s problem, then. The bigger worry is that another urgent security issue might appear on an already overloaded international agenda.