On Wednesday, the Senate rejected a one-time exemption from the filibuster for the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, effectively dooming the bill. One of its key provisions would have restored the preclearance provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), which the Supreme Court invalidated in 2013. My research shows that the previous version of preclearance helped increase the number of citizens who voted, thus helping to protect the right to vote.

Preclearance was one of the VRA’s most important provisions. It required certain jurisdictions with histories of disenfranchising voters to get the Department of Justice’s approval before changing any voting practices or procedures. But in its 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision, the Supreme Court effectively suspended preclearance by declaring its “coverage formula” unconstitutional.

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. argued that it was “irrational for Congress to distinguish between States in such a fundamental way based on 40-year-old data, when today’s statistics tell an entirely different story.” The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dissented, saying that the decision would mean a “second generation” of disenfranchisement.

Since Shelby, states and local governments have changed voting in ways that make the exercise of the franchise harder, especially for minorities; many of these changes probably would have been blocked under preclearance.

My research compared voting in North Carolina counties, some of which had been subject to preclearance and some of which had not. I found that preclearance was, indeed, still making a difference up until it was struck down.

The court’s decision was at odds with the reasoning behind the Voting Rights Act

The VRA dismantled many of the electoral underpinnings of the South’s Jim Crow system. President Lyndon B. Johnson declared its passage “a triumph for freedom as huge as any victory that has ever been won on any battlefield” and hailed it as “one of the most monumental laws in the history of American freedom.” It didn’t just prohibit voting practices and procedures that intentionally discriminated on the basis of race or color, but it also barred practices that had racially discriminatory results.

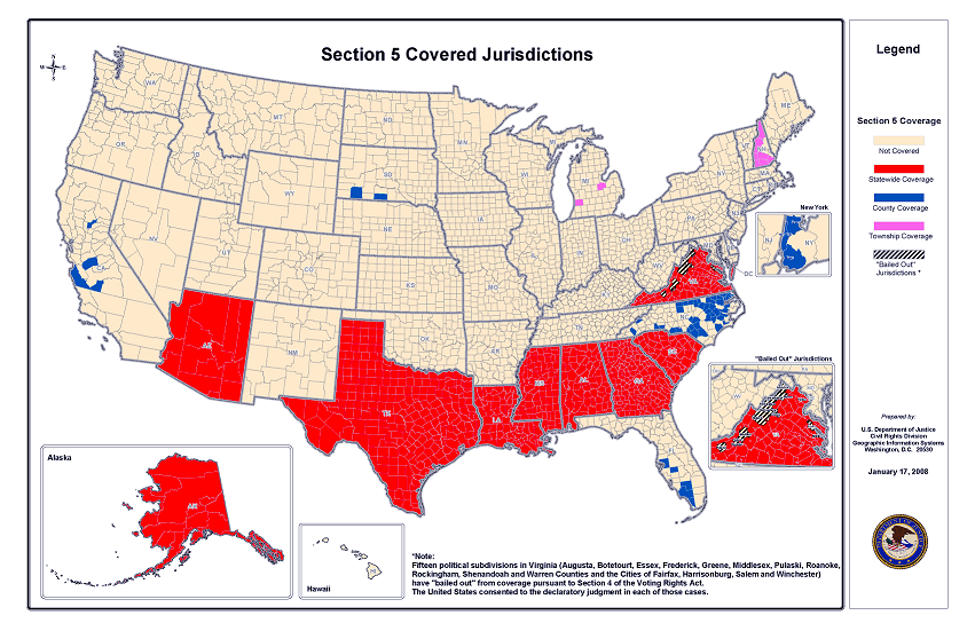

The VRA’s Section 4 formula declared jurisdictions to be “covered” by preclearance if they had used discriminatory “tests or devices” (such as literacy or education tests) or “good morals” requirements to limit voter participation, and if voter turnout or registration in the 1964 presidential election was less than 50 percent of the eligible population. Covered jurisdictions had to submit reports showing that any proposed voting changes neither discriminated against minority voters nor had a discriminatory impact, and they had to get the Justice Department’s approval before putting those changes into practice. From 1965 to the 2013 Shelby decision, the DOJ received 556,268 preclearance submissions. Most were approved. Around 3,000 proposed voting changes were denied.

Congress renewed this formula in 1968 and 1972. In 1975, Congress extended the act to cover language minorities. Congress again renewed the VRA, including preclearance, in 1982 and 2006 with nearly unanimous bipartisan support; Presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush, respectively, each signed it into law. When the Supreme Court struck down preclearance in 2013, nine states were fully covered jurisdictions, and in six states, some counties or municipalities were covered.

Preclearance led more Black Americans to vote

After the VRA passed, Black citizens voted at dramatically higher rates, particularly in the South. Between 1964 and 1968, statewide voter turnout in the presidential election rose by 7.3 percent in South Carolina, 9.0 percent in Virginia, 16.8 percent in Alabama, and 19.3 percent in Mississippi.

My research compares voting rates in all 100 North Carolina counties between 1950 and 2016. Doing this, I could estimate the consequences of the preclearance requirement specifically. That’s because North Carolina was the only state in which some counties (39) but not others (61) were covered by preclearance in 1965; an additional county was covered in 1975, with the language-minority extension.

Although North Carolina had a statewide literacy test (which remains in the state constitution), voter turnout was 52 percent in the 1964 presidential election, above the 50 percent cutoff. But that average was misleading: North Carolina’s counties had extremely varied turnout rates, ranging from 25 percent to 91 percent, and Section 4 applied to those with less than 50 percent. Examining county-level voting data, I was able statistically to distinguish the impact of preclearance from other factors and trends that affected all of North Carolina.

So how did preclearance affect counties that were otherwise similar? Significantly. Covered counties had 10.9 percent higher turnout than would have been expected in presidential elections without preclearance, holding everything else constant. In midterm elections, the effects were even bigger, with an estimated 14.4 percent voting increase above what would have been expected.

My research found similar patterns in voter registration. Here, I compared counties that had less than 50 percent turnout but close to that mark (and therefore subject to preclearance) with counties slightly above 50 percent (and therefore free of preclearance). In the first two midterm election years, 1966 and 1970, voting-age Black Americans were registered to vote at a 12.8 percent higher rate in preclearance counties than in counties that barely missed preclearance. For the first two presidential elections, 1968 and 1972, Black registration in the preclearance counties was 23.2 percent higher than in those not covered.

In other words, the original preclearance requirement increased voter participation significantly right after the VRA’s passage, with continued increases up until 2013.

So how did the elimination of preclearance affect all this after 2013? Comparing 2016 to 2012, voters in counties formerly covered by preclearance were significantly less likely to turn out than their peers in counties that were never covered. Additional research could reveal longer-term negative implications.

Nicole E. Willcoxon (@NWillcoxon), PhD, is a nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution.