About 67 percent of 900 million eligible voters turned out to vote in India’s recent general election, which Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, “Indian People’s Party”) won.

Yes, most commentators cautiously expected a BJP victory. But the surprise was that the BJP-led coalition claimed 352 seats and roughly 40 percent of the votes. For some analysts, there is concern that this landslide win could signal the end of India as a secular state. After all, Modi’s victory speech on May 23 lambasted “secularists” for what he said was their deceit.

Five years ago, the BJP won office by focusing on development. Modi promised a stronger economy, and some of the ideas implemented by his government yielded results. The Swachh Bharat (“Clean India”) campaign provided millions of toilets to rural communities, and many poor families received free liquefied petroleum gas as a cleaner-burning alternative to wood and other materials used as fuel for cooking.

It’s World Toilet Day. Why do so many people lack adequate sanitation facilities?

But other BJP economic policies foundered. “Demonetization” — the removing of counterfeit notes — was a fiasco, at least in its sudden implementation. And, overall, India’s unemployment has grown, and farmers have faced severe hardships.

Perhaps to skirt these economic shortcomings, Modi focused much of his recent campaign on identity politics. The BJP — described in Western media as a “Hindu nationalist” party — ran on a platform of Hindu majoritarianism. One of the candidates the party fielded was Pragya Thakur, who is accused in a 2008 bombing and who recently praised Nathuram Godse, the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi.

BJP President Amit Shah pledged to remove all immigrants from India except Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs and Jains. Likewise, Modi’s speeches were filled with menacing references to disloyal outsiders.

So what does the BJP’s victory mean for Indian secularism?

What is Indian secularism?

First off, the term “secularism” is quite different in Indian politics — it’s not what U.S. audiences imagine it to be: a separation between church and state. Instead, it refers to religious neutrality (dharmnirpekshta): the equal treatment of all religious communities, irrespective of size, by the government.

Secularism in India is less concerned with religion interfering in politics (as in the United States) than with the state interfering in religion. As Rajeev Bhargava argues, Indian secularism is about maintaining a “principled distance” between the state and religion.

India’s election results were more than a ‘Modi wave’

To get a better understanding of secularism in India, I conducted research in villages in the northern Indian state of Bihar in late 2017, and in February 2018, I conducted a survey of 900 Hindus across the state on religion and politics.

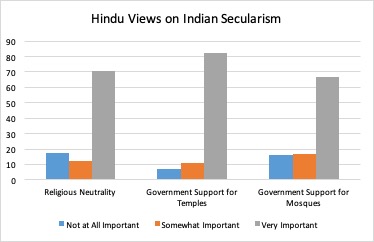

My preliminary findings show that Hindus in Bihar overwhelmingly support many of the ideals of Indian secularism — even government support for mosques. Critically, however, this is not true for more pious Hindus: The more religious voters are, the more they subscribe to the tenets of Hindu nationalism, especially the idea that Hindus deserve preferential treatment over Muslims.

My research

Bihar has a population of roughly 100 million people — imagine one-third of the U.S. population in an area the size of Indiana. The survey on religion and politics crossed three districts, with a sample proportional to the number of people who lived in urban and rural areas. Women — whose views on politics are often overlooked by scholars — were half of all respondents.

I asked Hindus in Bihar three central political questions: How important is religious neutrality? How important is government support of temples? How important is government support of mosques. I asked respondents to rank their answers using a scale from 1 (Not at all important) to 3 (Very important). As the figure below shows, Hindus overwhelmingly supported all these measures.

I also wanted to capture the views of more-pious Hindus, as the BJP used religious appeals to target these voters. But doing so entails answering a difficult question: What does piety mean for Hindus?

Western countries often measure religiosity as belief in God and attendance at religious services. But these views may not translate into the Hindu context, where a pious Hindu might be an atheist who never visits a temple. That’s one of the ways Hinduism differs from Western religious traditions.

I spent time in villages outside Patna, the capital of Bihar, and used open-ended questions to understand how Hindus conceptualize religiosity. The people I met highlighted puja (worship), adhering to rules about ritual purity and pollution, beliefs in auspiciousness/inauspiciousness, and their daily attire (e.g., wearing the tilak, a red mark on the forehead). I created a questionnaire using these understudied expressions of Hindu religiosity and constructed a scale of piety based on how participants responded.

More-pious Hindus think Hindus deserve preferential treatment

I found that pious Hindus are more likely to reject the idea that all religions deserve equal treatment. While they think the government has a duty to support temples, they do not think the same about mosques. Few Hindus espoused openly bigoted views of Muslims; rather, they simply thought that Hindus, about 80 percent of the population, deserved preferential treatment over Muslims, who make up only 15 percent of India’s population. This is, at its core, the idea of a “Hindu state.”

How India holds an election with 900 million voters and 8,000 candidates

To be sure, Hinduism is a diverse religion, and a study of Bihar may look very different from a study of other states. As Katharine Adeney has pointed out, a national-level survey shows that to a majority of Indian voters, democracy means that “the will of the majority community should prevail.”

Also, it is important to remember that my survey looked only at Hindus. An important remaining challenge is understanding why non-Hindus — including millions of Muslims — voted for the BJP, a party that could ostensibly threaten their safety and security.

In “The Desecularization of the World,” Peter Berger argued that one reason for the reemergence of religious politics in the 1980s was that political elites in developing countries, many of them Western-educated, forced secular policies on unwilling populations.

Did this happen in India? In any case, my research suggests that most Hindus in Bihar seemed to support the ideals of Indian secularism. But if the BJP continues to dominate Indian politics, and if it can succeed in making Hindus more religious, the future of secularism could look bleak indeed.

Don’t miss anything! Sign up to get TMC’s smart analysis in your inbox, three days a week.

Ajay Verghese (@ajayverghese) is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of California at Riverside and author of “The Colonial Origins of Ethnic Violence in India” (Stanford University Press, 2016).