2023 has been a year rife with human rights challenges. From Russia’s ongoing war of aggression in Ukraine, to civil conflict in Ethiopia and repression of Uyghurs and other minority groups in China, to the Israel-Hamas war, individuals and communities around the globe are suffering.

Good Authority contributor Kelebogile Zvobgo asked K. Chad Clay, associate professor in the Department of International Affairs at the University of Georgia and co-founder of the Human Rights Measurement Initiative, to offer a retrospective on the state of international human rights this year.

Kelebogile Zvobgo: It’s been a busy year for human rights, scholars, analysts, and practitioners. Well, I guess it’s a busy year every year for us. But this one does feel different in important ways. I’m wondering – from your perspective, what are three of the biggest human rights challenges from this year?

Chad Clay: Yes, it’s been a busy, busy year. And it’s been a tough year on the human rights front. I’ll pick three overarching issues I’ve observed over the last year, but these are three of so many.

2023 marks the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). At a milestone anniversary like this one, you tend to reflect on how things are going. And, in general, I think many of us are struck by the inadequacy of the international institutions we have for facing the enormous challenges of our time. Of course, I don’t want to undercut the declaration; it’s important for us to recognize the monumental contributions it has made and acknowledge how important it is that we’ve built an international human rights regime from it.

Tell us a little bit about the “international human rights regime.” What exactly are you referring to?

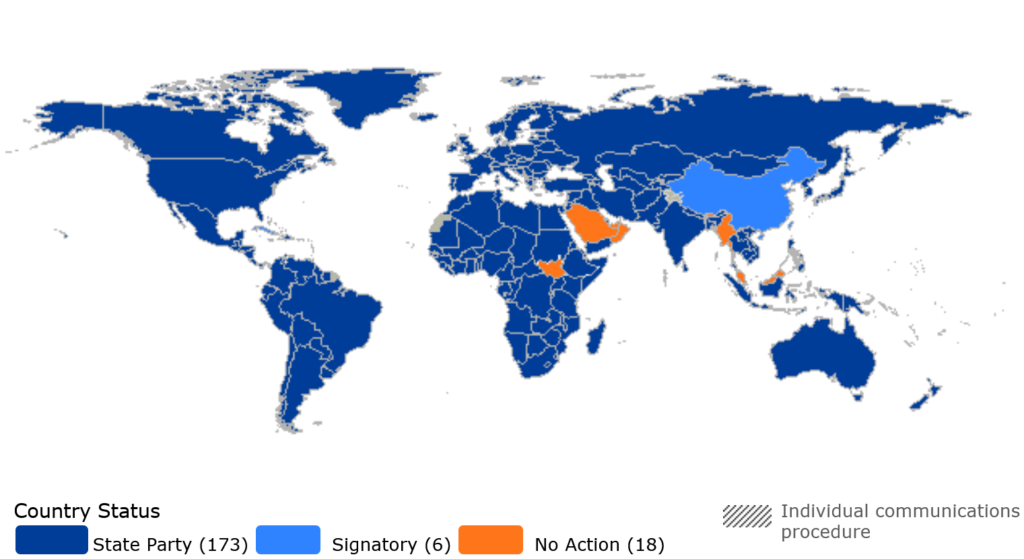

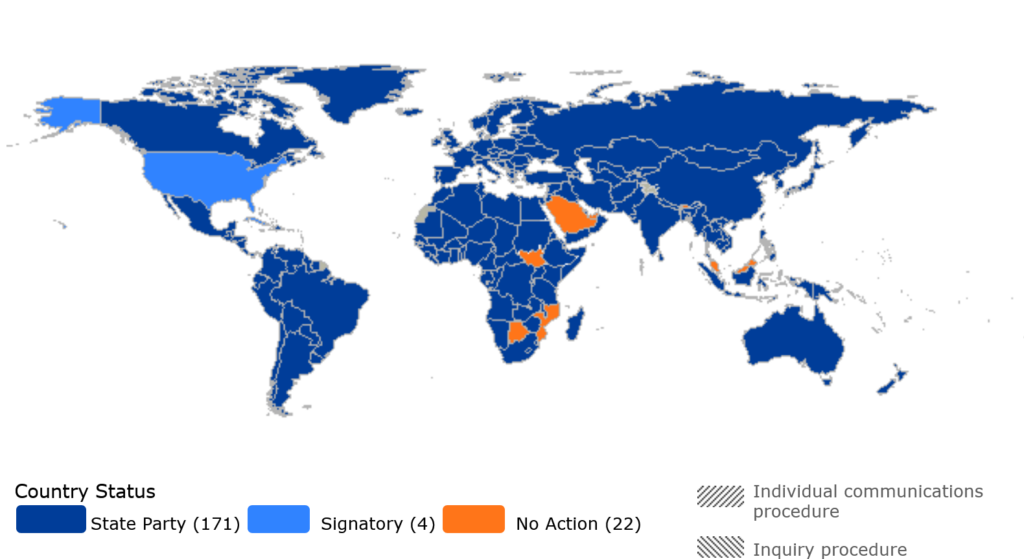

I’m primarily referring to treaties at the United Nations that build on the UDHR. As a declaration, the UDHR wasn’t legally binding like a treaty. Rather, the UDHR defined for the international community what human rights are. The two “omnibus” treaties that turned the UDHR into law are the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

How did we get these treaties? Were they forced on states?

States wrote them together and they were presented to every country in the United Nations. The vast majority of states, more than 170, have ratified the ICCPR and ICESCR, as the next two figures show. States have bound themselves to these and other human rights treaties. And all U.N. members, that’s more than 190 countries, have accepted the UDHR.

That we have these treaties and that we’re talking about human rights the way we talk about it now, a lot of that can be credited to the UDHR. Human rights are a work in progress – and 75 years seems like a long time in a human life. But it’s not a very long time in the history of the world or in the history of these concepts.

I hear people chalking up the challenges they read about and hear about as failures of human rights as a framework and failures of the international human rights regime, rather than opportunities to think about ways we could strengthen that framework and regime and make it more effective. That concerns me. When I think about this in terms of domestic laws, we don’t suddenly start deciding not to have laws against murder because murders happen. Instead, we think about ways to make those laws more effective.

I think the international community, and especially those of us who work in the fields of international law and human rights, needs to take some time to think about how we actually strengthen human rights, how we actually strengthen international law, and how we could actually make the regime more adequate for dealing with the challenges we face. I’m really afraid of us as a society giving up.

This is a very helpful primer, Chad. Thank you. With these ideas established, let’s get back to human rights challenges of the past year.

Right. First, I would say, is the rise of far-right parties and challenges to democracy – particularly in democracies and places where we haven’t expected that in the past.

Yes. My colleagues at Good Authority have been covering far-right parties and their ascendancy. Editor Erik Voeten recently covered the surprise win of the Party for Freedom, which has an extreme party platform in the Netherlands, including “banning the Quran, mosques, and Islamic schools, reintroducing work permits for European Union citizens, holding a referendum on leaving the European Union, a halt to immigration, ending climate change policies,” and others. It’s terrifying. What’s else?

Second are the various challenges to sovereignty of peoples and nations – from the transformation of Hong Kong into an authoritarian state resembling mainland China, to conflicts in places like Ukraine, Ethiopia, Sudan, and Israel and Palestine. None of these are new challenges, to be clear, but they are especially notable ones this year.

A third challenge is making human rights data more available and accessible, not just to policymakers, not just to advocates, but also to everyday people who are just trying to make sure that their interaction with the world, and their money in the world, isn’t doing harm.

These are all critical topics. I’m also curious about how you and your colleagues at the Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) are approaching these three issues, especially the third one. How does this initiative help make human rights data more accessible?

HRMI, for short, is an international collaborative project between human rights scholars, practitioners, and advocates that aims to produce useful data, in theory for everyone, on every human right and international law for every country in the world. Now, we’re far short of that goal right now; that’s the long-term goal.

At this point, we have data on different economic and social rights across as many as 190 countries and data on up to 40 countries for nine different civil and political rights. We also have some other specific datasets that are regional, for instance, a dataset that focuses on issues raised by human rights advocates in the Pacific.

But the goal here really is to make data that’s rigorous enough that those of us in social science see them as high-quality data that we can use in our work. And it’s important that the data also are accessible and understandable enough that human rights advocates, journalists, and lawyers can use them in their work. Ultimately, we hope that everyday people can go and get a quick understanding of a given country’s human rights practices.

Can you give us some top-line findings from HRMI?

One of the big top-line findings of the last few years has been the decline of respect for what we call “empowerment rights” in Hong Kong since the Chinese government passed a national security law for Hong Kong. There’s been an increasing crackdown on pro-democracy movements, journalists, and others in Hong Kong who are critical of the Beijing government. And slowly but surely Hong Kong’s scores on things like the right to assemble and the right to associate, or the right to express oneself freely and the right to participate in government, have converged with those that we see in mainland China. Prior to this law, people in Hong Kong enjoyed more of these rights than people in the rest of China, at least to some degree.

Another top-line finding relates to the United States, and it’s a finding that I think surprises most people. The United States overall appears to be one of the worst-performing high-income democracies in the world, across most areas of human rights.

What are some of the areas of human rights where the U.S. falls behind its peers? Can we take stock of the country’s performance?

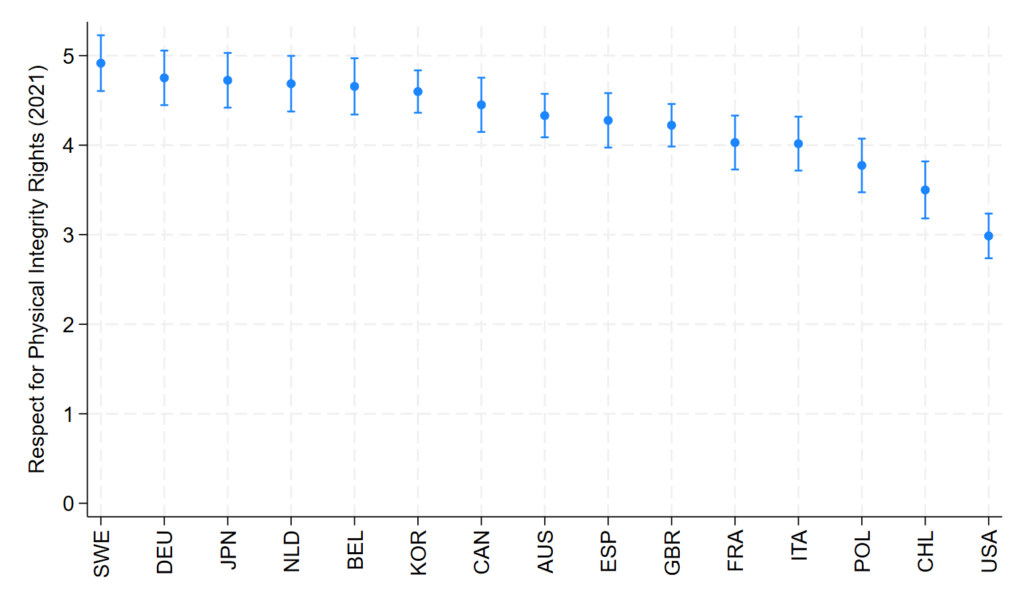

In general, the United States has the worst physical integrity rights practices in its peer group – things like the right to be free from forced disappearance, the right to be free from political imprisonment, the right to be free from arbitrary imprisonment, from extra-judicial killing, from torture and ill-treatment. The U.S. usually comes in around last on all of those among our high-income OECD countries in the HRMI data. In a recent version of the Rights Investor data produced by HRMI’s partner organization Rights Intelligence, the United States ranked 114th out of 195 countries in 2021 (see the figure below).

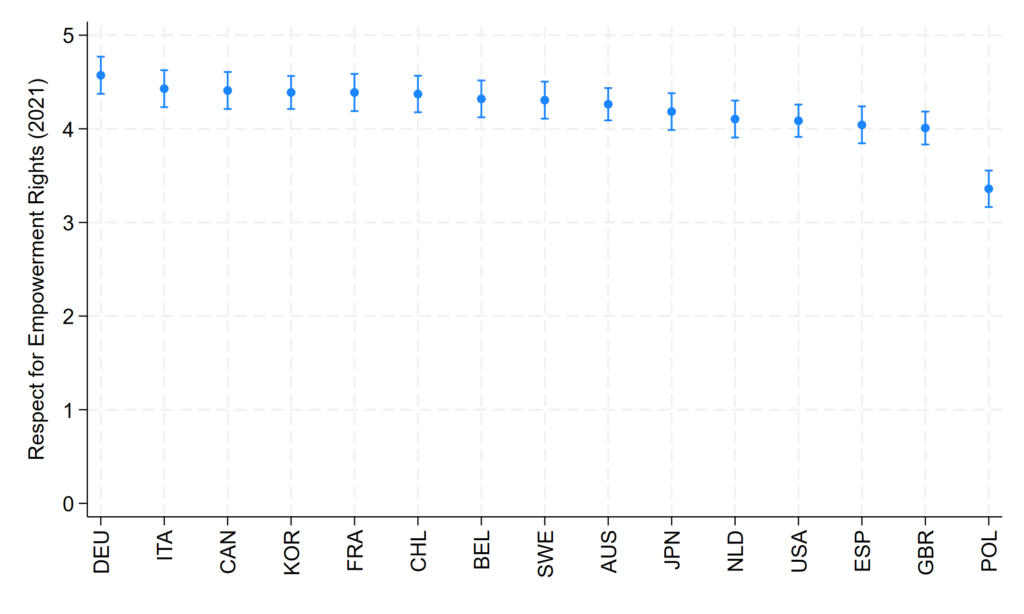

We are also far below where a lot of people would assume the United States would come in on empowerment rights. That’s freedom of expression, freedom to assemble and associate, the right to participate in government. In fact, the United States is still coming in very, very close to last among high-income democracies on empowerment rights (see below).

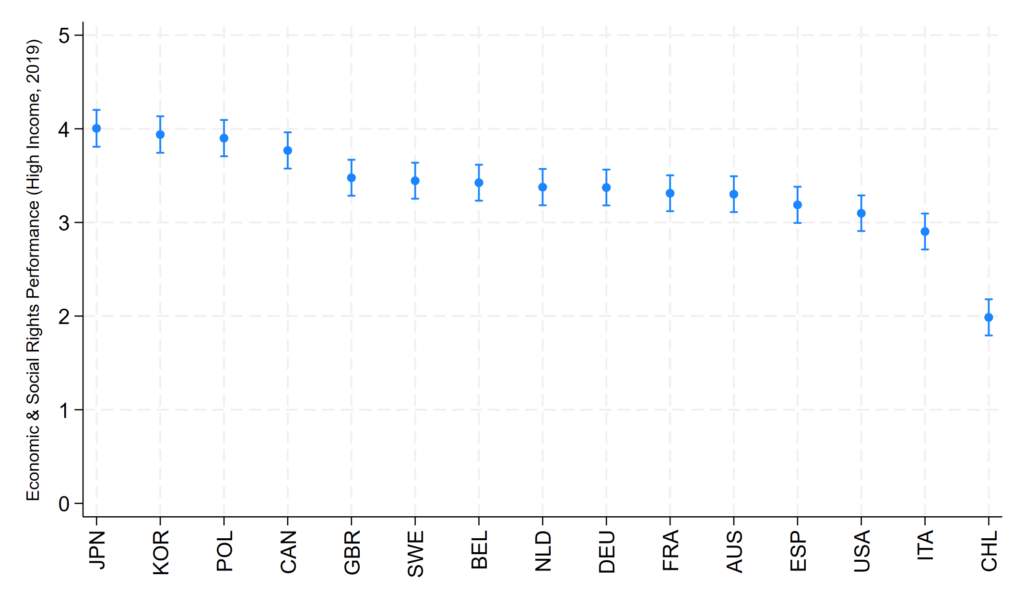

On economic and social rights, the United States typically comes in the bottom 5 to 10 high-income democracies on every single economic and social right we measure (see below).

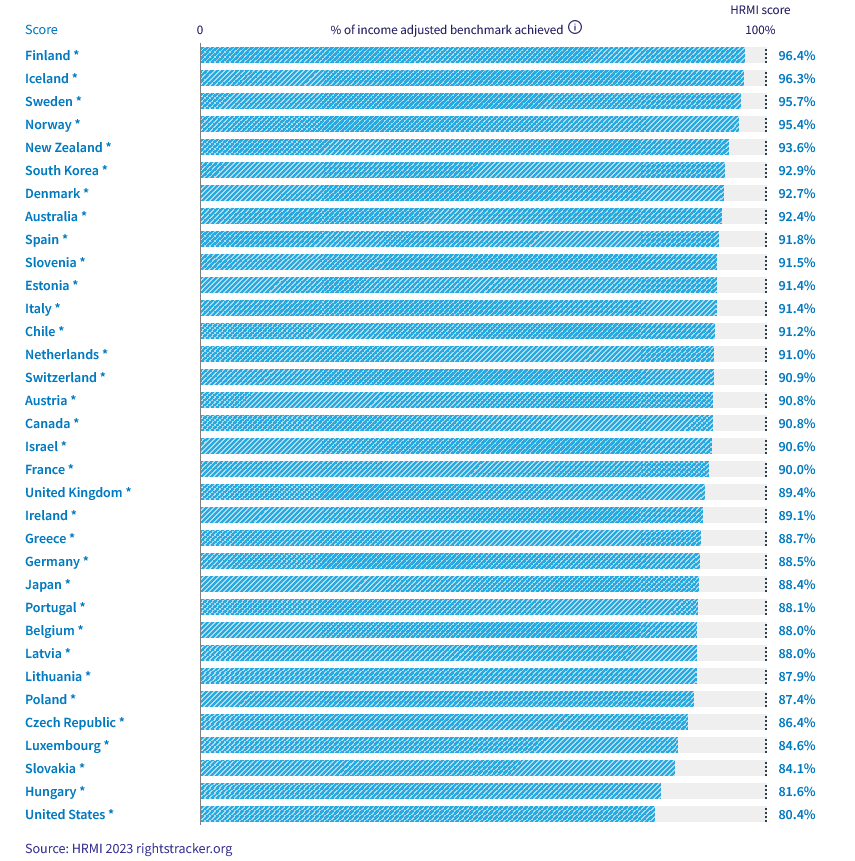

And, according to HRMI data, the United States ranks absolutely last on the right to health – see the HRMI figure below.

This is all very striking. We don’t tend to hear a lot about U.S. human rights practices in the news and, I would say, even in human rights scholarship. The U.S. is not often a subject of scrutiny aside, maybe, from torture allegations during the war on terror. Can you speculate as to why there is this omission or oversight?

I think some of the problem is that, in terms of human rights, the narrative has often been set by people based in the United States. And people based here have a tendency to not view human rights as a problem here. There’s a number of reasons that could be; it could be because of the national narrative the United States has for itself. I do think that the sort of center of gravity that the United States has been for the human rights community has led the country to often go by the wayside, and particularly in academic analyses of human rights.

I would say Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and other international human rights organizations have done a pretty good job of holding many countries – including the United States – accountable on human rights. I just don’t know that U.S.-based human rights scholars have always thought of the country in the same light.

I also think that the United States performs uniquely because, for all of the official U.S. rhetoric about being a major supporter of human rights, we actually haven’t participated in the international human rights regime the way other countries have. The United Nations tends to talk about 18 major human rights agreements. Well, the United States has only ratified five of those: the ICCPR, but not the ICESCR, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, the Convention Against Torture, and then two optional protocols to the Convention on the Rights of the Child but not the main treaty.

That puts us in some really interesting company. I was talking about U.S. performance on economic and social rights being pretty poor earlier. Well, the United States is the only OECD member state that hasn’t ratified the ICESCR.

What are some of the rights covered in that treaty that, perhaps, would lead the United States to not want to be a member?

One that’s widely debated in the United States is the highest attainable standard of health, as it’s written in the ICESCR, and also the right to housing, to food, to education. There are a number of rights that I think in the United States, and in the political debate, have often been treated, quite frankly, not as rights. They’ve been treated as political things to be debated, but not things that people are entitled to, merely thanks to their humanity, even though they’re obviously necessary for human flourishing.

The United States is also one of a handful of countries that hasn’t ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and is literally the only country in the U.N. system that hasn’t ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

So the United States is a significant outlier. This is just something that you don’t get to say about other high-income democracies, that they don’t participate in this international human rights regime to this extent. And I think it’s bad for U.S. human rights practices. I also think that U.S. non-participation is bad for the international human rights regime and bad for U.S. attempts to improve human rights around the world. It opens up the door to allegations of hypocrisy and of whataboutism when it comes to U.S. leadership and the country’s hegemonic role in the international system. This non-participation is bad for everybody.

It’s nearly the end of the year. Looking back on 2023, and recent years as we’ve been discussing, makes me want to look forward. And I’m wondering, looking forward, what ordinary people, human rights advocates, and even policy makers can glean from the HRMI data? What might help launch us into action in 2024, to promote human rights?

I think there’s a lot we could do. I’ll initially just direct everybody toward HRMI’s website. If you go to the “In the Media” and the “Data in Action” sections of the website, we have so many examples of people using the data in different ways – in domestic advocacy, to demonstrate to governments that they are falling short in one human right or another. In terms of international advocacy, the HRMI data are frequently used in civil society submissions to the U.N. Universal Periodic Review and to human rights treaty bodies, to demonstrate how a country is doing and how it could be doing better. National human rights institutions around the world use the data.

And, again, everyday people are using it in their own personal advocacy to get news out into media outlets and to explain to people overall how human rights practices are going in their country. So first, I would direct people to the data. There are many ways to use our data that can drive change.

Beyond that, my take on our data, and something I’m actually doing research on right now, is that data makes stories more powerful, and stories make data more powerful. One of the best examples I have of this is in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder in May 2020. During that time period I found myself interacting with a lot of people who previously saw U.S. police in a very different light, who had previously viewed the police as being incapable of carrying out human rights abuses on the level of what we observed with George Floyd. Many people who saw his video of this horrible thing happening came to me and said, “This thing is wrong. But you know this is an isolated incident.”

What was so powerful in that moment was to be able to come to them with data and say, “But it’s not. It’s not an isolated incident; this is something that is a representative event of something that happens frequently.” If you look at the number of people killed by police in the United States and you compare it internationally, the United States typically falls in the top-10 countries with the most killings by police. For a lot of people, I’m sure it’s difficult in their daily lives to wrap their heads around that. But when you have a story that brings it to the surface, like what happened to George Floyd, and you’re able to pair that with data demonstrating this isn’t a one-time event, this isn’t just a bad apple, this is something that happens all the time – it’s powerful.

And so if I’m asked how people can use the data in their everyday life, that’s one way I would suggest using it – with their friends, family members, people around them, to demonstrate that the anecdotes that they have are actually pieces of data, pieces of a larger picture. And it’s a picture that we can change if we want to, if we try to.