Everyone seems to be celebrating 2019’s record number of women in U.S. politics. You’ve probably seen the Nancy Pelosi clapping memes and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s smile all over the news for introducing the Green New Deal, beating out Massachusetts Sen. Edward J. Markey for the lead credit. Even President Trump congratulated the large contingent of white-suited female lawmakers during his State of the Union address. And a record six women (and counting) are seriously in the running for a major party’s nomination for president — an array we’ve never seen before.

Few people would have predicted all this just two years ago, when Trump’s 2016 victory over Hillary Clinton struck many as a blow against U.S. gender equality. What happened? And what does this mean for the future of U.S. politics?

What changed?

After the 2016 election, an enormous number of people, especially women, dove into political activism, many for the first time. Informally known as “the resistance,” this wave channeled political frustration into everything from organizing town halls to public protests and is credited with helping to turn out record numbers of midterm voters and electing high numbers of female candidates. In a recent paper, we found an especially high level of this activism among youth — specifically, adolescent girls who identify as Democrats.

That wasn’t what many expected after Hillary Clinton’s loss. On the one hand, many — including the candidate herself — framed Clinton as a role model, particularly for young people. On the night she secured her nomination, Clinton tweeted a picture of herself dancing with a little girl at a campaign event. The tweet read, “To every little girl who dreams big: Yes, you can be anything you want — even president. This night is for you.” On the other hand, many Democratic women felt the 2016 election’s outcome was the opposite of inspiring.

How did all this affect the young women watching?

How we did our research

To find out, we analyzed a nationally representative survey of 997 adolescents age 15-18 and their parents, conducted online by YouGov. Both teens and parents responded to two waves of this survey, the first during the fall 2016 campaign and a follow-up roughly one year later, in the fall of 2017. We asked about their views of American democracy and political engagement. By interviewing the same people both before and after the election, we can see whether their attitudes changed.

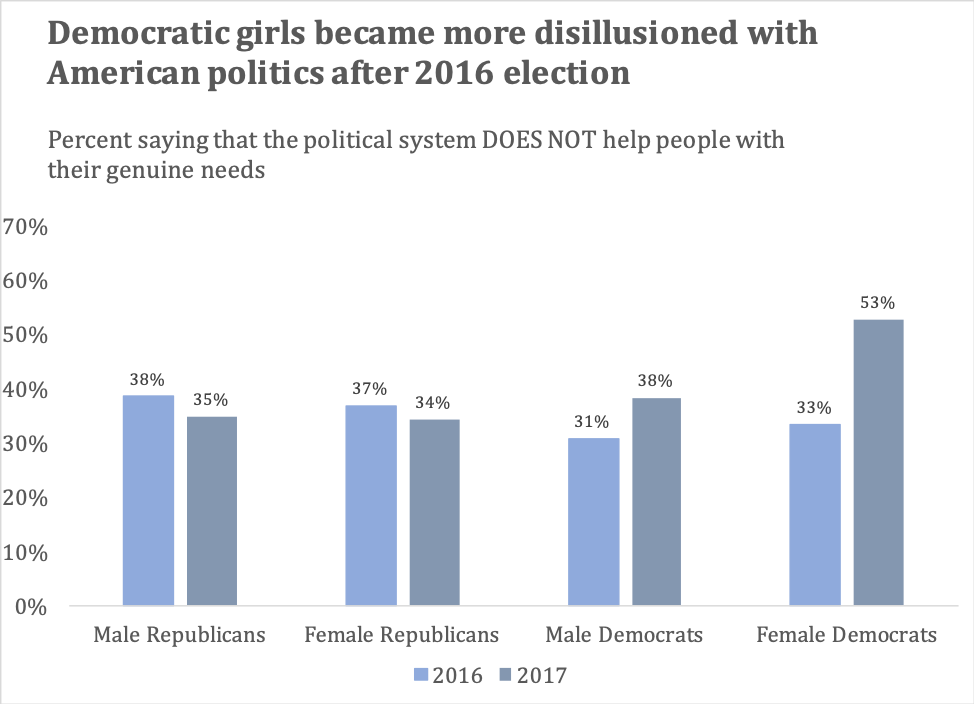

Here’s what we found. First, disillusionment with the political system rose dramatically — but only among girls who identify as Democrats. Before the election, as you can see below, Democratic girls had the same view of American democracy as everyone else.

In the fall of 2016, about a third of Democratic girls said that the political system in America “does not help people with their genuine needs,” a proportion nearly identical to that of Democratic boys and of both male and female Republican young people. One year later, 53 percent of Democratic girls now said that U.S. democracy does not help people with their needs — a significant jump, especially compared to the fact that the opinions of the other groups barely budged. (Both Republican boys and girls became slightly less likely to say that the government does not help people with their needs, presumably because their candidate won the election).

Past research has suggested that when people are disillusioned with democracy, they often disengage. Why bother getting involved if all is for naught? But after the 2016 election, Democratic girls who came to doubt American democracy responded quite differently.

As you can see in the figure below, Democratic girls say they became more politically active — and particularly, more likely to say that they are or plan to be engaged in lawful political protest. The biggest spike came among those Democratic girls who became disillusioned. Instead of dampening their enthusiasm for political engagement, their doubts about the state of U.S. politics seem to have increased their desire to be heard.

So why might Democratic girls in particular become interested in protesting after the 2016 election? We suspect that they’re following role models — but not that of just one woman politician. The January 2017 Women’s March, the largest single-day demonstration in U.S. history, protested Trump’s inauguration as president — and launched a wave of activism that has opposed Trump ever since. Across the nation, the majority of activists have been women. The protesters have used gendered rhetoric and symbols, such as the famous pink hats.

Economic anxiety isn’t driving racial resentment. Racial resentment is driving economic anxiety.

Not surprisingly, adolescents, regardless of party or gender, who had a parent engaged in protest after 2016 were more likely to say they would protest themselves. But Democratic girls whose parents didn’t protest also expressed a desire to take to the streets. Why? Democratic girls have had other visible role models — including women marchers and organizers in their communities and nationwide — for how to channel their post-2016 political frustration. Many have come to see protest as an important part of their own political repertoire. “The Resistance” is the role model.

How Trump speaks like a mob boss

What it means for the future

While it is too early to tell, we may be witnessing an emerging generation who are primed for political engagement. Just like baby boomers who came of age during the protests of the 1960s and then remained engaged over their lifetimes, today’s Democratic girls may be launched on a lifelong trajectory of political activism.

In short, one lasting consequence of the Trump era may be a cohort of politically active women — not just in Congress but in our communities — whose entree into politics can be attributed not only to inspiration but also to indignation.

David Campbell is a professor of political science and chair of the political science department at the University of Notre Dame. He is co-editor of “Making Civics Count: Citizenship Education for a New Generation” (Harvard Education Press, 2012).

Christina Wolbrecht (@C_Wolbrecht) is a professor of political science and director of the Rooney Center for the Study of American Democracy at the University of Notre Dame. She is the co-author, most recently, of “Counting Women’s Ballots: Female Voters from Suffrage Through the New Deal” (Cambridge, 2016).