When Rwandan President Paul Kagame took the stage as the keynote speaker at last year’s annual assembly of the World Health Organization, WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus greeted him a warm handshake.

Kagame, reelected in 2017 with 98.7 percent of the vote after 18 years in office, is one of a new group of autocrats to find accolades for improving health. For decades, China and Cuba stood out for providing good health coverage at low cost.

Rwanda, along with Ethiopia, Myanmar and Uganda, rank among the least democratic nations in the world, but each of those nations extended their average life expectancy by 10 years or more since 1996 and did so with the heavy support of foreign aid.

But new research suggests that elections and health are increasingly inseparable. Our new article in the Lancet details the first comprehensive study to assess the link between democracy and disease-specific mortality in 170 countries between 1980 and 2016. Here are key takeaways about democracy and health.

1. Democracy matters more for chronic diseases.

The Lancet results show that a nation’s democratic experience — a measure of how democratic a country has been, and for how long — contributed more than a country’s gross domestic product to explaining reductions in deaths from cardiovascular diseases, cancers, transportation injuries and tuberculosis. In contrast, we found no significant link between democracy and deaths from malaria, HIV and most other infectious diseases.

What explains this difference? Prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases, cancers and most other noncommunicable diseases depend on government action more than most infectious diseases. Aid initiatives can deliver food, vaccines and anti-malaria bednets in settings with dysfunctional governments and limited infrastructure. But only local governments can implement and enforce the excise taxes and advertising restrictions that reduce tobacco use. Treatment of cancers and cardiovascular disease is chronic and costly, requiring governments to provide trained doctors, nurses, hospitals and surgical facilities.

Second, the effects of democracy are greatest for the diseases that foreign aid does not tend to target heavily. Two percent of aid addresses noncommunicable diseases, which cause most deaths worldwide. Tuberculosis is the leading infectious disease killer globally, but it receives less aid than efforts to prevent and treat HIV, malaria and childhood diseases.

Should health care be treated as a human right?

Without pressure from voters or support from foreign aid agencies, autocratic leaders have less incentive than their democratic counterparts to invest in the laws and health-care infrastructure needed to prevent and treat chronic diseases. This may explain why autocracies have not been as successful in health coverage when their populations’ health needs shifted to care for chronic diseases.

Here are some examples. China’s hospitals are plagued by long lines and reports of frustrated patients attacking physicians. Cuba maintains a low child mortality rate, but its struggles to provide health care to adults led one commentator to remark, “Cuba is a good place to be born but a dreadful place to have cancer.”

2. Where democracy matters on health, it will matter more in the future.

Deaths from stroke, breast cancer and other noncommunicable diseases are surging in many poor nations. As infectious disease and child deaths decline, the number of adults in poorer countries is increasing rapidly. Adults have adult health problems, and these are disproportionately noncommunicable diseases. In poor countries with underdeveloped health systems, those diseases arise in younger people and produce worse outcomes.

African governments are far from powerless in global health initiatives like those against AIDS

In 1990, noncommunicable diseases represented a small share of the overall health burden in Myanmar (35 percent) and Ethiopia (17 percent). A recent study projected that share to increase to 82 percent in Myanmar and 67 percent in Ethiopia by 2040.

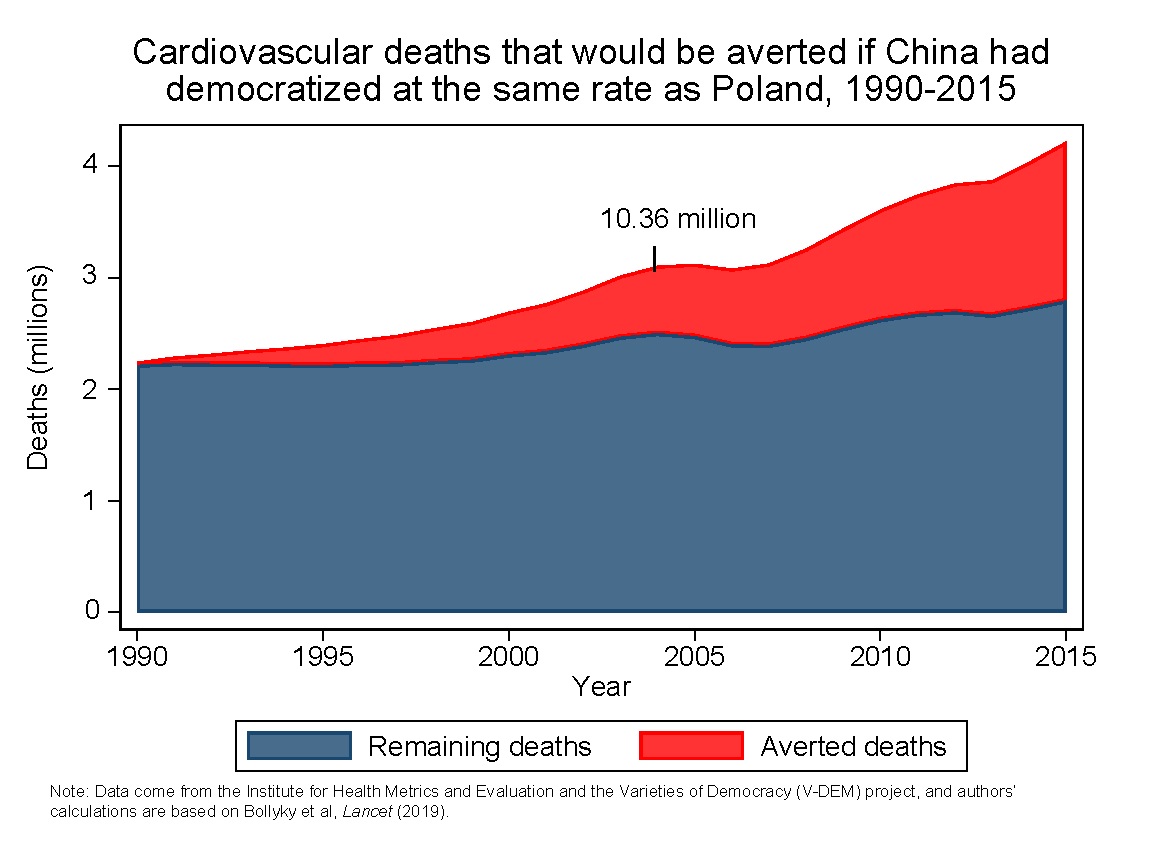

The Lancet study shows that each one point increase in a country’s democratic experience was associated with a roughly 2 percent decline in deaths over 20 years from cardiovascular diseases, transportation injuries and tuberculosis, respectively. Between 1995 and 2015, we estimate that increases in democratic experience averted 16 million deaths from cardiovascular diseases globally.

Those results, as shown above, suggest that autocracies such as China, where noncommunicable diseases now cause most deaths, might deliver better health to their populations if those nations had transitioned to democracy at the same rate as other nations.

3. The health effects of democracy are not just a by-product of increased wealth.

The effects of democracy on health can be difficult to measure. Many wealthy nations are democracies and spend more on health.

The Lancet study applies a variety of statistical tests to minimize the risk that the effects attributed to democracy are a by-product of greater wealth. One of those tests reveals that increases in a nation’s democratic experience do not have a significant tie to increased GDP per capita — but are correlated with fewer deaths from cardiovascular disease and more government health spending.

4. Free and fair elections are the critical factor.

The components of democracy — which include suffrage, freedom of association, freedom of expression and an elected executive — work synergistically, but the Lancet results suggest that free and fair elections are essential for improving health. Without free and fair elections, the health benefits of democracy cease to be statistically significant — they effectively disappear.

How do resource-constrained countries commit to universal health care?

Here’s why: Free and fair elections force governments to answer at regular intervals to a broad set of citizens for adopting proven treatment and prevention measures, which exist for stroke and coronary heart disease. In contrast, autocracies, where opposition parties are illegal or elections are rigged, answer primarily to minority groups in power, or military and business interests. Autocracies may also be more likely to withhold health and welfare services from supporters of opposition groups.

5. The future of global health is political.

This observation that democracy and health are inescapably linked may discomfort aid officials who depend on productive relationships with local, often autocratic governments to succeed. But many current goals in global health — from universal health care to tobacco taxes to affordable cancer drugs — are political. These issues involve fundamental questions regarding the role of the state in society and the balance between individual, collective and commercial interests. Ignoring the role of civil society, a free media and accountable government in resolving these debates undermines efforts to build the institutions and the popular support needed for sustained health improvements.

Tom Bollyky is the director of the Global Health Program at the Council on Foreign Relations and author of “Plagues and the Paradox of Progress: Why the World is Getting Healthier in Worrisome Ways.” Follow him on Twitter at @TomBollyky.

Tara Templin is a health policy PhD student at Stanford University.

Simon Wigley is associate professor of philosophy and department chair at Bilkent University.