The federal government is about to run up against its borrowing cap — the “debt limit” or “ceiling.” Set by Congress and the president, this limits how much the federal government can borrow. Treasury estimates its coffers could run dry by Oct. 18, after which Treasury would run out of cash needed to meet all of its obligations on time — including paying interest on the national debt, sending benefit checks to Social Security recipients and veterans, and so on. The impasse would probably severely damage an economy still recovering from the coronavirus pandemic, roiling markets and potentially throwing millions of people out of work.

Battles over raising or suspending the ceiling have been a staple of congressional politics for decades. This time, GOP lawmakers argue that Democrats should raise the ceiling on their own, since they are planning to incur debt by enacting President Biden’s Build Back Better plan.

But that’s not how the debt limit works. Lifting the ceiling allows Treasury to borrow enough money to pay for policies Congress has already adopted. That includes the trillions of dollars in pandemic relief and tax cuts Republicans enacted during the Trump administration.

Nevertheless, Senate Republicans blocked a Democratic measure last week that would lift the ceiling — trying to force the majority to instead raise the limit through a special reconciliation budget bill. Another test vote comes this week.

Here’s what you need to know about the rocky road ahead.

Debt-ceiling drama isn’t new

Partisans have tussled over raising the debt limit for decades. Every president since Dwight D. Eisenhower has signed at least one bill to raise the ceiling. Since the 1950s, the House and Senate together have voted more than 100 times on measures related to the debt limit. So far, the parties have been unwilling to simply abolish the debt ceiling.

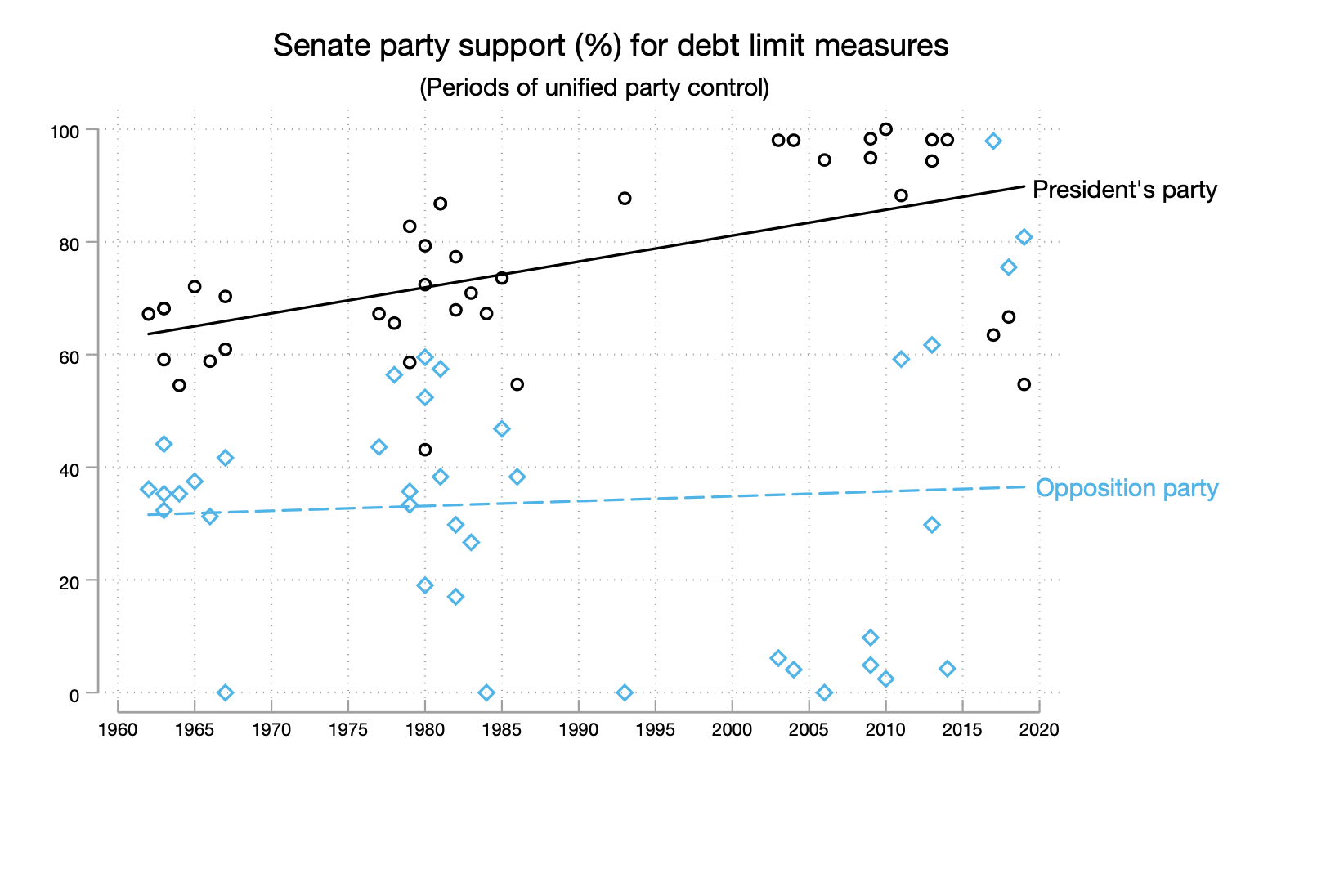

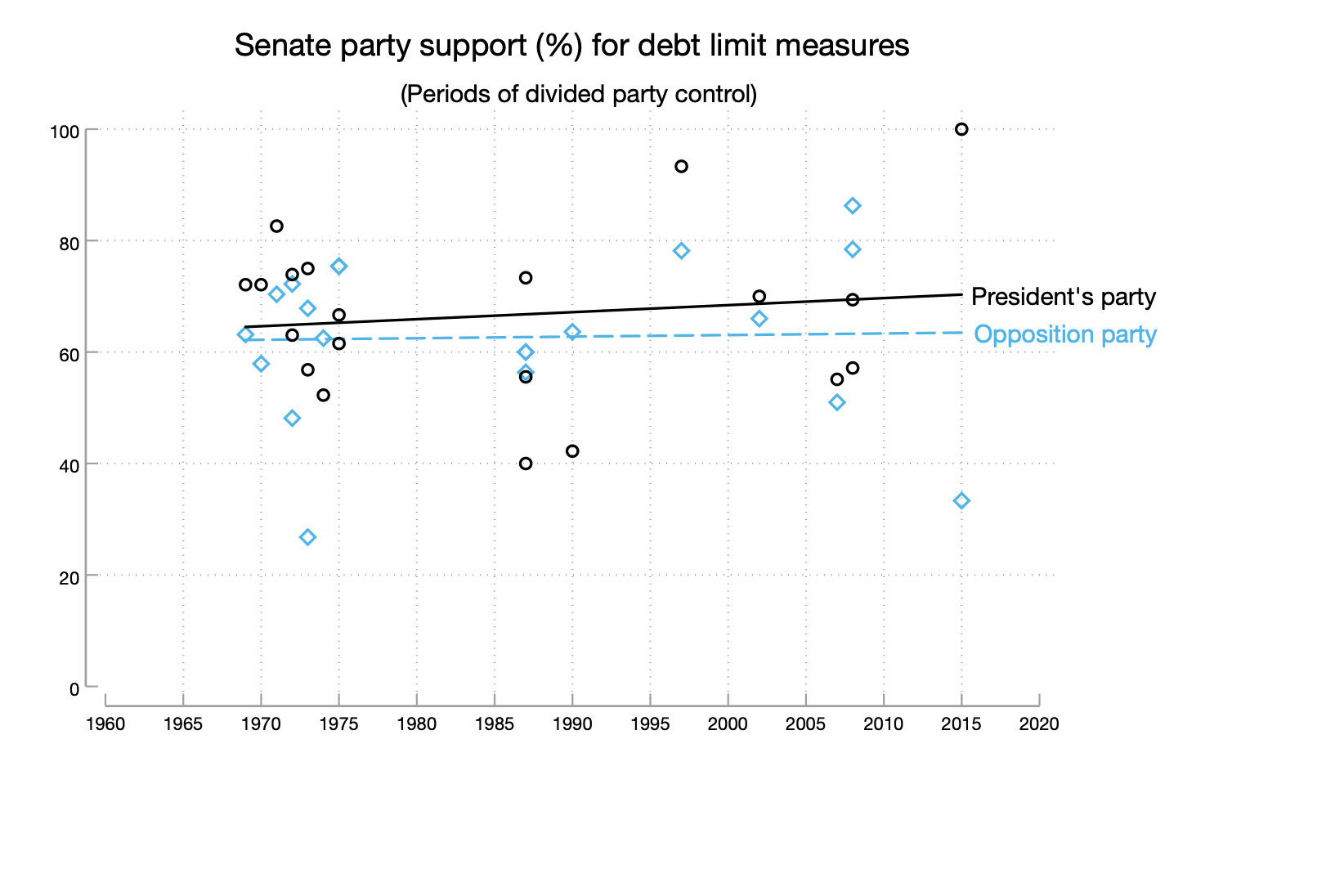

Responsibility for raising the limit always falls more heavily on the president’s party, especially in periods of unified party control. And knowing that the ceiling must be raised, the president’s critics often take the bill hostage to gain leverage for fiscal policy demands. Even if opponents back down, the president’s party must typically cast politically charged votes to raise the ceiling. When the parties divide control of government, both parties usually pony up votes.

Those patterns are visible in the graphs below, which update Senate voting data on debt limit measures from political scientist Frances E. Lee’s 2016 book, “Insecure Majorities.” The first figure shows how partisans have voted when the president’s party controls the Senate. As Senate majorities have shrunk and partisanship has increased, the president’s party now shoulders most of the burden. But when control is divided, as you see in the second figure — and therefore voters would find it hard to blame one part or the other for the impasse — both parties support must-pass votes.

So far, this time feels a little different

Congress hasn’t confronted the debt limit since the Budget Control Act (BCA) expired in 2020. The BCA imposed legal limits on domestic and defense spending programs between 2011 and 2020. Most Democrats abhorred the domestic caps, while Republicans hated limiting defense. Together, the parties routinely adopted bipartisan measures to lift the caps. Party leaders artfully tucked language into those measures nearly every time to address the debt limit, dodging a government default.

Without the BCA, lawmakers have lost a politically palatable vehicle for lifting the debt limit. The Senate is the problem. When Democrats have tried to move measures this year to suspend the debt limit, Republicans have successfully filibustered. If the GOP would refrain from filibustering, Democrats could lift the limit with a simple majority vote. A few weeks away from Treasury’s as-yet-uncertain “X date” to act, Republicans vow not to give in.

The procedural minefield ahead

Republicans instead want Democrats to use a budget reconciliation bill to raise the debt limit, an approach that Congress hasn’t used since 1997. At this late stage, that’s not so easy.

Here’s the rub. To write a reconciliation bill, the House and Senate must first agree to a budget resolution that instructs relevant House and Senate committees to write the bill. Democrats have already adopted a budget resolution for the current fiscal year, and they did not include instructions directing committees to raise the debt limit. Most likely, that means both chambers would first have to agree to amending the budget resolution.

The first and last time Congress appears to have amended a budget resolution after it was passed was in 1977, under an earlier version of the Congressional Budget Act. The Senate parliamentarian has advised Democrats that they can take this path without jeopardizing the reconciliation bill they plan to use to advance Biden’s social policy agenda. Still, some uncertainty remains about the process and how long it would take to complete. And we don’t know yet whether Republicans would help rescue Democrats from any procedural land mines. Would Senate Republicans even show up for a vote in an evenly divided committee? If they didn’t, it would deprive Democrats of the quorum they would need to move the bill to the Senate floor.

Given how time-consuming reconciliation can be, the calendar could soon make it impossible. Senate Democrats seek to call Republicans’ bluff, daring them to filibuster debt limit bills as the X date nears. At least for now, Democrats lack the votes to ban filibusters on debt limit resolutions. That means the most viable option remaining would be for Senate Republicans to refrain from filibustering and allow Democrats to lift the ceiling on their own.

Even if Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) were to agree to this, he cannot block fellow Republicans from attempting a filibuster. In that case, if Democrats stick together, at least 10 Republican votes would be needed to end debate and break the impasse. Should Republicans refuse to cooperate, the United States could face an unprecedented government default and potential national and global economic debacles.