Joe Biden’s campaign aimed both to regain some of the support in middle America that Hillary Clinton lost to Donald Trump in 2016, and to appeal to highly educated white-collar workers, especially white-collar women. His electoral college victory and his increased vote share compared to Clinton suggest that he was successful.

In particular, Biden managed to improve upon Clinton’s vote totals among small- and medium-size metropolitan counties and in the suburban counties he targeted. He was less successful in moving votes outside metropolitan areas and in the big cities. The consequence is that this year’s voters were more polarized along rural-urban lines than in 2016.

How we did our research

To explore this topic, we relied on the National Center for Health Statistics’ 2013 urban-rural classification scheme of counties. That scheme divides counties into six groups, which we have further consolidated into four categories for ease of discussion:

- {‘type’: ‘text’, ‘content’: ‘Central counties of large metropolitan areas, greater than 1 million in population’, ‘_id’: ‘LVY6AIUI5ZHZRGM5YAEQFVR6VE’, ‘additional_properties’: {‘comments’: [], ‘inline_comments’: []}, ‘block_properties’: {}}

- {‘type’: ‘text’, ‘content’: ‘Fringe counties of these same metro areas, which we label “suburban”’, ‘_id’: ‘6I4I43ZI4ZBM5LF7DCRXDABDK4’, ‘additional_properties’: {‘comments’: [], ‘inline_comments’: []}, ‘block_properties’: {}}

- {‘type’: ‘text’, ‘content’: ‘Medium- and small-size metro areas of less than 1 million’, ‘_id’: ‘RSC2ZP3UEJBHNHP4FZH252TBPA’, ‘additional_properties’: {‘comments’: [], ‘inline_comments’: []}, ‘block_properties’: {}}

- {‘type’: ‘text’, ‘content’: ‘All other areas, which we term “rural”’, ‘_id’: ‘R33N64FVUJBLDAXWPL7SO775HM’, ‘additional_properties’: {‘comments’: [], ‘inline_comments’: []}, ‘block_properties’: {}}

To account for the fact that some states, especially California and New York, still haven’t completed their counts, we confine the analysis to counties where total votes reported thus far equal at least 90 percent of the votes cast in 2016.

Why did Biden win? Look at the fundamentals.

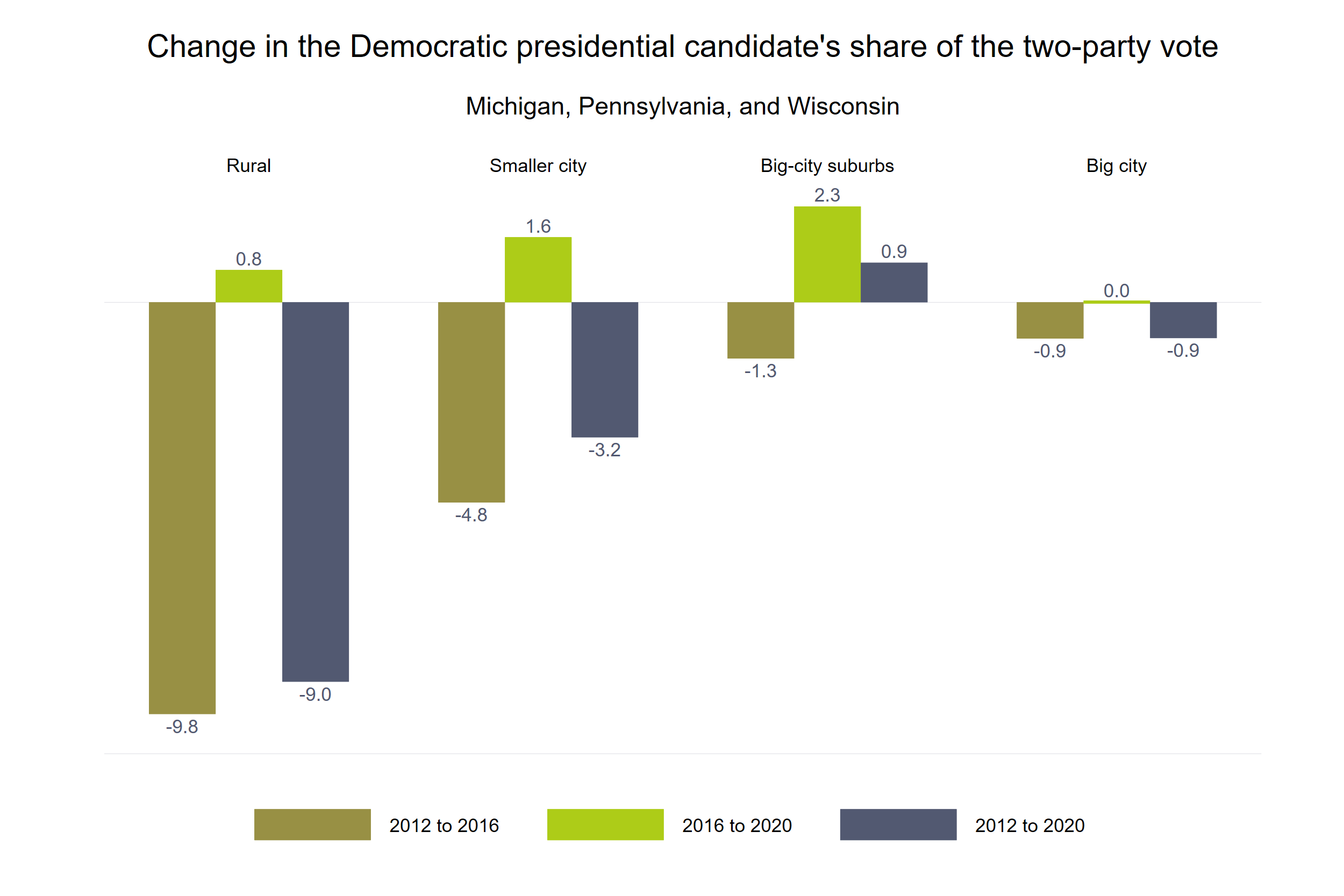

The rural-urban dimension of Clinton’s defeat and Biden’s victory in the Rust Belt

Clinton lost the 2016 election not so much because of how many votes she got, but because of where she received those votes. Clinton won 51.1 of the votes cast for the two main parties — just about a percentage point less than Barack Obama’s 52.0 percent in 2012. But her 49.7 percent share in the three pivotal Rust Belt states of Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania was nearly four points lower than Obama’s 53.6 percent. That sealed the election for Trump.

Clinton lost votes, compared to Obama, in all four of our geographic areas within these three states. But she did much worse in the rural areas, where she performed nearly 10 points below Obama, and in the smaller metro areas, nearly five points behind Obama. Given the close margin by which these states were decided, Clinton could possibly have won if she had held ground around the big cities of Milwaukee, Detroit, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. But she didn’t. As you can see in the figure below, she actually lost ground in the big cities and in their surrounding suburbs as well.

This year, Biden is winning the presidency with a 52.0 percent share of the two-party vote, nearly identical to Obama’s — and 0.9 points greater than Clinton’s. Most important for the electoral college, he regained Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, albeit without Obama’s comfortable margins. Biden was able to regain only 1.1 points of the 3.9 points that Clinton’s campaign had given up. Biden shifted the vote enough to win in 2020 — but that was too small to suggest a “blue wall” was rebuilt in the Upper Midwest.

Notably, Biden’s electoral gains were more focused than Clinton’s loses. The biggest were, not surprisingly, in the big-city suburbs, where he gained 2.3 points over 2016, and 1.6 points in the small- and medium-size metro areas. He gained only a little in the rural areas — and held his ground only in the big cities.

Biden’s failure to regain ground in the big cities suggests that he was elected by the wooable voters in the suburbs and smaller metro areas, rather than by mobilizing the area’s diverse urban populations.

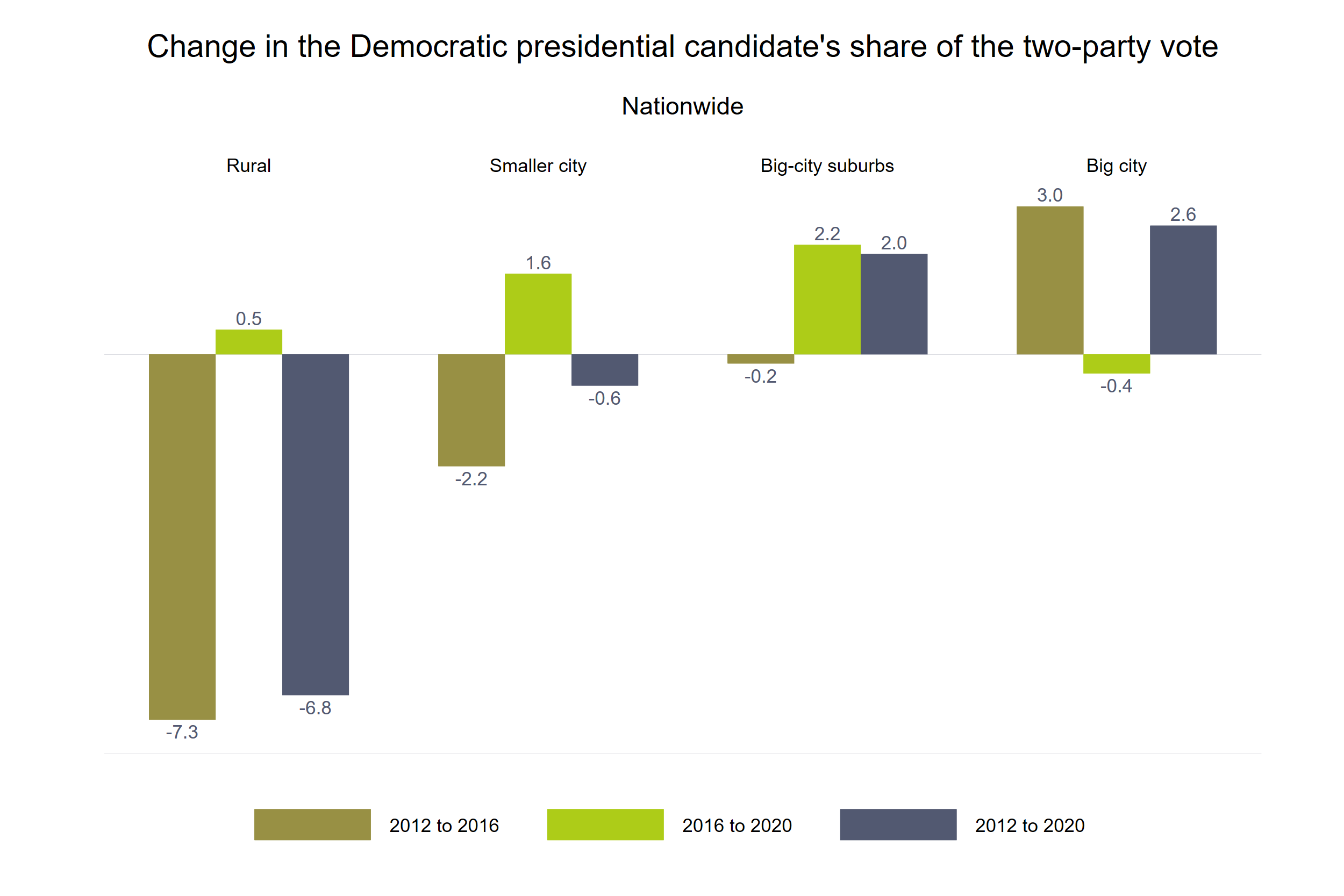

Biden’s gains in the rest of the nation were much like his gains in the Rust Belt

That geographic story mirrored what happened in the nation as a whole. Biden’s improvements in rural counties, small- and medium-size metro areas and in the big-city suburbs are quite similar to what we saw when we zoomed in on Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania. So was the lack of change in support in the big cities.

If you look closely, however, you can see one notable difference between the swing states and the nation at large. Unlike in the swing states, nationally Clinton actually improved over Obama in the big cities. Biden did slightly less well in these counties than Clinton — but he still managed to draw more big-city support than Obama. All this is consistent with what has been reported about Biden’s campaign strategy.

What does this mean for future presidential elections?

Presidential candidates now win or lose elections by extremely slim margins. At the same time, the nation has continued to undergo a “big sort,” in which urban and suburban dwellers vote Democratic and small-town and rural residents vote Republican. Over the last three elections, that’s given us an electorate neatly divided between rural and urban dwellers.

Between 2016 and 2020, votes shifted most in the middle of that rural-urban continuum. These regions’ voters are likely to be most prone to shifting again in 2024. If there really is a meaningful rural-urban continuum in electoral politics, these are the system’s median voters. Big cities’ suburbs and small cities and their white, middle-class voters may become the swing voters most chased by presidential campaigns.

Don’t miss any of TMC’s smart analysis! Sign up for our newsletter.

John Curiel is a research scientist with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Election Data and Science Lab.

Charles Stewart III (@cstewartiii) is the Kenan Sahin distinguished professor of political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and co-director of the Stanford-MIT Healthy Elections Project.