On Sunday, Argentine voters delivered a shocking electoral result for the third time in three months. Javier Milei, a far-right pro-market economist and television celebrity, won the presidential runoff with a sweeping 55.7% of the vote, defeating Sergio Massa, the incumbent finance minister.

A staunch libertarian, Milei rose to prominence through his TV appearances, in which he combined technical jargon – he even approvingly quoted Arrow’s Theorem to dismiss the value of democracy – with inflammatory remarks and strongly worded insults against his adversaries. His rage against the political establishment, which he calls la casta – literally “the caste,” or a privileged political class – endeared him to many young voters.

Milei ran his campaign on a personalistic party label, Liberty Advances, wielding a chainsaw – a symbol for cutting government spending – and promising to “destroy” inflation. Forty years after Argentina’s 1983 transition to democracy, Milei will become Argentina’s first outsider head of state.

How did an outsider win the presidency?

Two conditions explain Milei’s historic triumph. First and foremost, a ravaging economic crisis led a majority of Argentines to hold the incumbent left-wing Peronist government – especially Massa, the top economic official – accountable at the polls. Argentina’s year-on-year inflation hit 143%, the highest in three decades and currently the third highest in the world after Venezuela and Lebanon. The poverty rate is 40% and rising and the country is plunging into recession; the IMF expects Argentina’s GDP to contract 2.5% this year. Argentines’ views on the national economy are understandably grim: In LAPOP’s 2023 AmericasBarometer survey, 86% of Argentines told interviewers the national economic situation had worsened over the last year.

Ahead of the election, Massa and the incumbent administration pulled out all the stops. The Peronists activated their famous political machine and Massa spent 1% of GDP on government handouts in the weeks leading up to the October first-round elections, including a major income tax cut for all but the wealthiest strata. (Milei, who is currently a national deputy, supported the tax cut as well.) But even these unprecedented efforts proved insufficient to overcome the deep economic malaise.

Milei also benefited from the mainstream opposition’s failure to capitalize on the economic meltdown and spiraling anti-incumbent sentiment. Together for Change, a center-right coalition that governed between 2015 and 2019, ran a clumsy and disorganized campaign racked by internal frictions. The coalition’s candidate, former security minister Patricia Bullrich, failed to make it into the presidential runoff. In part, Together for Change was saddled by its own disappointing economic management during the 2015-2019 administration of Mauricio Macri, the coalition’s founder. Argentines have been unsatisfied ever since, surveys suggest.

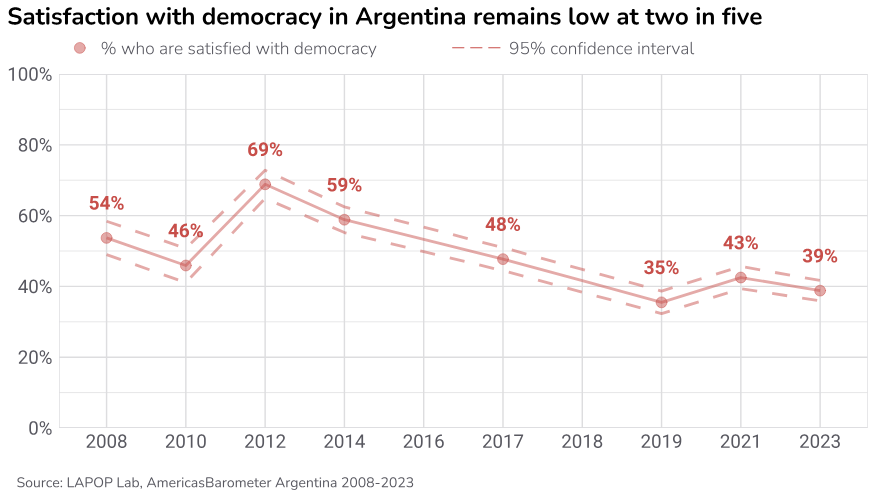

Drawing on nationally representative samples of voting-age respondents from LAPOP’s AmericasBarometer, the figure above shows the proportion of Argentine respondents that said they were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the way democracy works in Argentina in each round of AmericasBarometer between 2008 and 2023. In 2023, satisfaction with democracy in Argentina was 39% – marginally lower than the Latin American average of 41% – and remains significantly lower than 11 years ago.

Milei promised big changes – but these won’t be easy to make

Milei faces an uphill battle once he takes office on December 10. He has pledged economic shock therapy to end inflation by “setting the central bank on fire” and dollarizing the economy. Dollarization would mean abandoning monetary policy by ditching the devalued Argentine peso and embracing the U.S. dollar as the national currency. It’s an uncertain endeavor, as no economy of Argentina’s size has previously dollarized.

His proposed reforms against big government include privatizations, tax and expenditure cuts, trade liberalization, and labor-market deregulation. During the campaign, Milei also declared a “cultural battle” against feminism and socialism. He promised to shut down the ministry of women, gender, and diversity; abolish sex education in schools; and hold a referendum on repealing the 2020 law that legalized abortion. And he said he would sever commercial ties with Brazil and China, claiming he does not make deals with “communists.”

The big challenge is that, unlike any previous Argentine president, Milei faces extraordinary economic, political, and institutional barriers to his radical policy agenda. Dollarization, for instance, requires vast reserves of U.S. dollars, which the central bank simply does not have. (Tellingly, Milei barely mentioned dollarization in his victory speech or since election day.)

And the president’s powers have limits. In Argentina, tax and education policy are set by the congress, where Milei’s party has scarce representation. Liberty Advances holds only 38 seats out of 257 in the Chamber of Deputies and 7 out of 72 in the Senate. His party controls none of the country’s 24 powerful subnational governments. He may be able to win over some Together for Change politicians, but that will likely depend on his ability to achieve some quick economic wins.

And so, the candidate who spent his entire campaign railing against the political “caste” will now need the help of that same political class to pursue any of the policies he promised. The alternative, in the best case, would be political gridlock at precisely the time when desperate Argentines demand quick and unwavering solutions to economic hardship.

A much more troubling alternative for Argentina would be if Milei’s opposition actively worked against his success. For the outgoing Peronist administration – led by former president and current vice-president Cristina Fernández — an “era of resistance” will begin when Milei takes office. Given Peronism’s ties to labor unions and social movements, that resistance is very likely to involve large-scale strikes and demonstrations. With Milei’s own party so poorly represented in the national legislature, an emboldened opposition could even try to impeach him.

Indeed, Argentina’s last economic crisis, in 2001-2002, forced the sitting president to resign and resulted in a tumultuous succession of five presidents over the course of two weeks. To avoid a similar fate, Milei now has very little time to demonstrate to voters that he can achieve what he said the political establishment could not – turn Argentina’s economy around.

Adrian Lucardi (@alucardi1) is associate professor of political science at ITAM in Mexico City, and a visiting scholar at the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions at Vanderbilt University.

Noam Lupu (@NoamLupu) is associate professor of political science and associate director of LAPOP Lab at Vanderbilt University.

Jorge Mangonnet (@jmangonnet) is assistant professor of political science at Vanderbilt University.