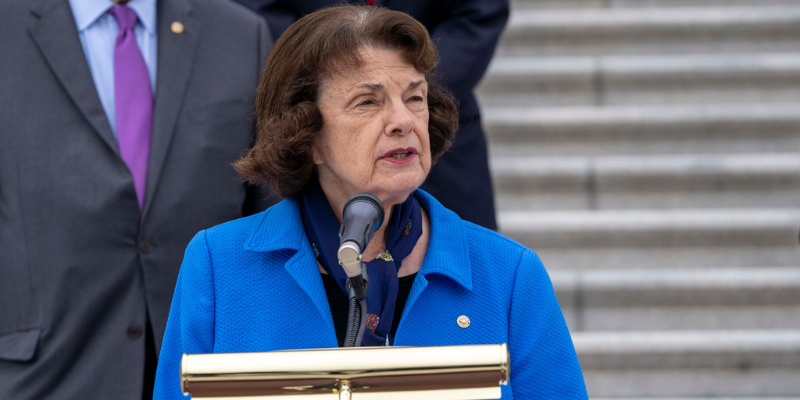

U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) died on Thursday evening in her Washington, D.C. home. In the coming days, the nation will remember Feinstein as a fearless feminist who often sought to change societal ills, such as gun violence. In a highly polarized political climate, is there anything to learn from Feinstein’s decades in public office?

Yes – at least one thing.

Not everyone will like you, so be okay with it

Towards the end of her career, Feinstein increasingly came under fire from members of her own party. Consider, for instance, the issue of Amy Coney Barrett’s nomination to the Supreme Court. As the top Democrat on the judiciary committee, Feinstein was instrumental in Supreme Court nominations. Political parties want elected officials to hold the party line. As such, the stance of party leadership and their messaging to the rank and file play an important role, as partisan politics increasingly dictate senators’ votes on nominees. As a steadfast supporter of women’s rights, Feinstein had long advocated for more women to enter politics. When she joined the Senate in 1992, only two other women senators were serving. As part of Feinstein’s lifelong push for gender parity, she seemed to support having a woman replace Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Supreme Court.

When Pres. Trump nominated Amy Coney Barrett in October 2020, liberal groups pushed back, wanting a justice in the ideological mold of Bader Ginsburg rather than a conservative nominee who was a woman. All the Democrats on the committee, including Feinstein, chose to abstain; Barrett advanced with only Republican support. Feinstein, however, seemed to quasi-support Justice Amy Coney Barrett, although she did not vote for her. After the hearing, Feinstein praised Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), noting, “This has been one of the best set of hearings that I’ve participated in.” These remarks drew the ire of progressives, especially at a time when partisan politics increasingly dictate senators’ votes on nominees. In response, Feinstein stepped down as the lead Democrat on the committee.

Dianne Feinstein’s long political career cannot be encapsulated in one remark in a Judiciary Committee hearing. But the Coney Barrett incident does show the complexity of how partisan women behave.

Partisans can be fickle. Some observers lauded Feinstein as a fierce advocate for women’s representation and rights as well as other liberal policies; others bemoaned that she was not liberal enough. Today she is remembered as a centrist Democrat. Yet, Feinstein was self-confident as the longest-serving female senator and was not easily deterred by what was said about her.

Toward the end of her career, progressives called for Feinstein to retire due to her age, poor health, and questions about her mental capacity. Was it sexist to levy these attacks against Feinstein? If so, Feinstein would have been familiar with sexism. She entered the Senate in 1992, in an election called “the Year of the Woman” since it brought a wave of women to Congress, after many voters were outraged by the all-male Senate committee hearings on Clarence Thomas’s nomination to the Supreme Court, in which Anita Hill testified that he had sexually harassed her. Feinstein’s career involved a series of “female firsts,” as she became the first woman to occupy several elected positions. Her response to sexism was to dig in, and became accustomed to withstanding blistering criticism.

Feinstein has been significant to political science scholarship

Gender and politics research routinely notes that women are often above partisan rancor. As such, women are known to be bridge-builders while working along party lines. Women mayors tend to adopt approaches to governance that prioritize and reward congeniality. This is in contrast with men, who are more likely to emphasize hierarchical relationships. Women state legislators, too, are inclined to build and maintain collegial relationships with their colleagues. Scholars have found that this collegial relationship style bolsters the ability of congresswomen to “fit in” – an ability that benefits historically marginalized groups in finding community, a strategy that better enables them to advance their legislative priorities. However, other scholarship has shown that congresswomen are not that different from congressmen. While they aid in “democratic legitimacy” – meaning that citizens are more likely to respect government when more women are present – women do not reduce partisan divisions. In sum, new literature suggests that women are not less partisan than men; they just value collegiality more.

The scholarship on gender and politics further finds that self-confidence is a psychological benefit for women, improving their personal competence in politics. Studies have shown that the tendency of women to lack confidence partly explains why they do not run for political office in the same numbers as men. Confidence in women is also linked to having feminist sensibilities. Voters often negatively evaluate self-confident women candidates and feminist politicians. But women politicians need self-confidence as it is a known factor in political ambition.

Feinstein’s own words displayed confidence in her abilities to make change as an elected official. Her political ambition was fueled by an understanding that not everyone will like or agree with you as a woman politician. That did not seem to curtail her political career, which began in 1970 and involved 31 years of life as a senator.

Feinstein was among the reasons political scientists needed to study gender and politics

The study of gender and politics owes a lot to Dianne Feinstein. She exemplified the need for women’s political representation – for instance as an author of the Violence Against Women Act – which provided substantive representation for women. She served as a role model for women and girls who dared to enter politics; scholarship notes that such models are important in encouraging candidates to emerge. Feinstein entered Congress during what was called the “Year of the Woman,” when women were elected to Congress en masse in the largest numbers that the federal legislature had ever seen. This, among other contemporary elections worldwide, led to scholarship on critical mass and women’s representation, which would have been impossible before. Her life demonstrated the importance of institutional power for women. Scholarship on women’s political leadership and the institutionalization of racialized and gendered norms in Congress are possible because women like Feinstein were able to achieve seniority and become fixtures in Congress. The gender and politics subfield of political science raced to keep up with Feinstein, as seen in the research questions asked during her illustrious political tenure in efforts to answer the scholarly puzzles posed by her leadership.

Perhaps the next frontier for gender and politics scholarship will be to rigorously evaluate women’s postmortem political lives. Certainly, much can be gleaned from how trailblazing political women lived their lives, affected politics, and impacted how we currently engage with politics. As we go further in this direction, political scientists can borrow from Feinstein’s example of being okay with whatever we think of her. Much is to be learned from historic firsts beyond symbolic representation. To do so requires that we humanize these pathbreaking politicos, and do not place them on pedestals. They lived in a political world that found fault with them, and were not immune to criticism. We can learn from how they handled that criticism – particularly women politicians, who are often stereotyped as risk averse. Despite this, women politicians are changing how we study politics and the political world.

For her part, Feinstein chose to remain in office – ultimately, dying in office, even though she had announced that she would retire at the end of 2024. Even in death, Feinstein responded to critiques on her own terms and in her own way.