As anti-racism efforts unfold across the United States, we see racial minorities in solidarity with one another. But are they participating as individual African Americans, Latinos and Asian Americans — or are they politically engaged as members of a shared group?

My research suggests it is probably the latter.

At nearly 40 percent of the population and growing, nonwhites are no longer minorities or roving bands of disparate groups. Many nonwhites today identify as “people of color,” rejecting any notion that their lives are politically marginal.

I say this confidently because I have observed people of color’s politics in the past three years across large-scale surveys and experiments that involved nearly 15,000 people, while conducting personal, in-depth interviews with 25 carefully selected black, Asian and Latino adults. My research reveals that the label “people of color” was created by — and for — African Americans and has evolved into an identity that politically mobilizes many nonwhites toward common goals — unless “people of color” feel that others in the coalition are ignoring their own racial group’s unique challenges.

Think racial segregation is over? Here’s how police still enforce it.

An identity reflecting racial diversity

Public discussion often overlooks the fact that groups called “minorities” can choose from several identities. A “person of color” identity is a new entry in the portfolios of nonwhites, who can identify primarily as black, Latino, Asian; Mexican, Jamaican, Chinese; or Catholic, Methodist, Muslim. Under many circumstances, they now choose to identify as POC.

Starting in 1965, immigration-induced growth introduced new “minorities” with varied histories. Black leaders emphasized the points of commonality with the new term “people of color,” whose popularity grew.

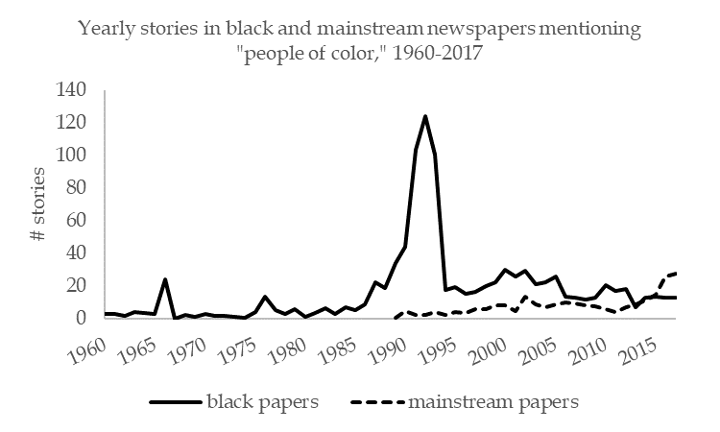

To find out how, using digital archives for four major mainstream newspapers and three major black newspapers, I gathered and read stories that mentioned the term “people of color” since 1960. As you can see in the figure below, black newspapers like the Los Angeles Sentinel were using this term long before, and much more often than, mainstream newspapers like The Washington Post.

In the figure below, you can see the yearly percentage of stories in black papers using “people of color” to refer not just to blacks but also other nonblack groups like Latinos. In the late 1980s, roughly half their POC usage began referring to both blacks and another minority group.

“People of color” identity addresses inequalities

To understand this new identity, in 2018, I partnered with the survey firm Dynata to conduct three parallel online surveys of African American, Latino and Asian American adults, with 1,200 opt-in respondents per group matched to U.S. Census benchmarks. I asked them to complete four statements about how important being a “person of color” is to them, such as, “Being a person of color is a major part of how I see myself.” I combined these responses into a score where higher values reflect stronger POC identity. I also measured respondents’ support for #BlackLivesMatter, where higher values indicate greater BLM backing. A stronger level of POC identity is strongly associated with support for BLM among black, Latino and Asian adults, independent of other influences like personal ideology. This pattern also emerges on other political issues, like support for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and curbing police brutality.

Why non-Black people of color can face racism and still be racist

Identifying as a “person of color” means viewing oneself as an interchangeable member of a shared group, where one’s unique identity as black, Asian or Latino is nested under a broader POC category. In fall 2019, I conducted a unique lab experiment with 350 African American, Asian American and Latino college undergraduates, ages 18 and older, from the participant pool of the UCLA Race, Ethnicity, Politics & Society Lab. Members of each racial group automatically associated their own group and other nonwhites with the category “people of color” — a snap judgment made instantly.

Black people have protested police killings for years. Here’s why officials are finally responding.

When galvanized, POC identity directs attention toward racial disparities, their structural roots, and the role of white supremacy in generating them, as illustrated by recent protests against police brutality. While the protests stress black individuals and themes, they include other “people of color” who have agreed (consciously or not) that solidarity is what this moment requires; that a black issue is their issue, too; and that while other problems can be placed on this agenda — for instance, reducing the detention of immigrant children — now is the time to keep the focus on brutality against black bodies.

The limits of a “people of color” identity

I sometimes hear complaints about “people of color,” including grumbles from nonwhites themselves. In-depth interviews with 25 “people of color” during 2019 brought such comments as, “Not everyone likes this label,” “it flattens differences” and “it simplifies complexities.” But, of course, such characterizations are correct about any identities.

I’ve found that when “people of color” feel that their narrower racial group’s unique challenges are being ignored, the unity behind “people of color” crumbles. In 2019, I undertook three experiments with 900 African American, Asian American, and Latino participants through Prolific, an online survey platform. Within each group, a random half of respondents read demographic information adapted from the U.S. Census Bureau explaining that “people of color” are a substantial portion of the United States population, while reminding readers that POC face shared inequalities.

The second random half of respondents read the same information, but with an added sentence arguing that comparing the experiences of blacks, Latinos and Asians is like comparing apples and oranges: While POC all experience discrimination, the legacies of slavery cannot be compared to, say, the challenges of undocumented immigration. I found that individuals in the first group expressed about 14 percent more favorable feelings toward other “people of color” than those in the second group.

The TMC newsletter has moved! Sign up here to keep receiving our smart analysis.

Genuine support

There is nothing natural about camaraderie among people of color. For every commonality, a point of difference intrudes on unity. But the many Latinos, Asian Americans and other nonwhites standing behind African Americans today are there in genuine support of their cause as “people of color.” They all have skin in today’s game of racial politics.

Read all of TMC’s analysis of the Floyd protests and Black Lives Matter here.

Efrén Pérez (@EfrenPoliPsy) is a professor of political science and psychology at UCLA, where he is director of the Race, Ethnicity, Politics & Society Lab.