Myanmar’s military — known as the Tatmadaw — is taking clear steps to preempt large-scale popular resistance to its power grab. Within a week of seizing power, the military has arrested key civil society leaders, blocked Internet and phone connections, and imposed martial law across major cities.

On Monday, the Tatmadaw banned gatherings of more than five people, but collective acts of civil disobedience and street protests continue to gather momentum across the country with support from millions of Myanmar’s people online, likely leading to further repression by the Tatmadaw.

So what is the Tatmadaw likely to do? My research on the urban pro-democracy movement gives some clues. During 2017-2018, I carried out 100 in-depth interviews with Myanmar’s residents, and gathered written testimony from local journalists and political activists who have experienced the Tatmadaw’s counter-mobilization strategies firsthand during previous periods of military rule. Here’s what I learned.

The Tatmadaw relied on three key strategies to suppress activism

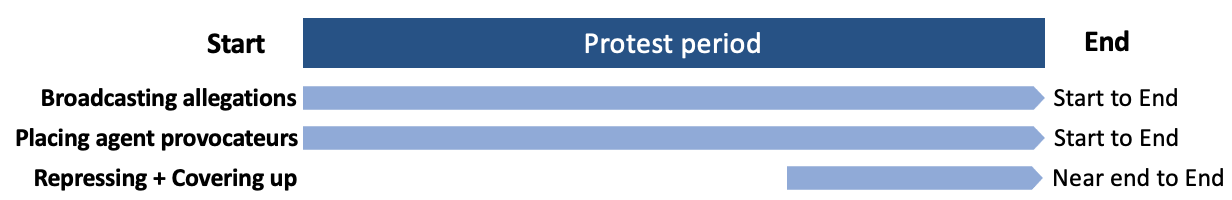

During five decades of military rule, Myanmar’s generals employed three main strategies to discredit popular demonstrations and legitimize state repression, as shown in the figure below.

First, military regimes tried to frame protesters as “rioters” by spreading allegations about violence. Many residents recalled how Myanmar’s state-owned media became a rumor mill, spreading accusations that “rioters” were hiding among demonstrators to rob properties, poison food and water, burn cars and destroy factories and offices. At the height of the Four-Eight Uprising in 1988, the Burma Socialist Programme Party regime blamed rioters for shutting down government offices that the regime had closed. By broadcasting multiple unsubstantiated claims, the authorities wanted to make the public perceive an immediate threat from protests and refrain from supporting or participating in opposition gatherings.

Second, to buttress its rumors, the military deployed agents provocateurs to infiltrate peaceful protests and instigate riots. During the 2007 Saffron Revolution, these agents attacked the security forces with bricks and rocks, allowing the military to justify shooting protesters later on. At the height of the Four-Eight Uprising in 1988, the Tatmadaw also had military agents poison public water sources to make local residents become hostile toward all suspicious-looking strangers, including protesters.

Third, the military junta cracked down on protesters, using these unfounded accusations as a pretext. Even so, Myanmar dictators actively covered up scenes of mass repression to prevent public backlash. In particular, Yangon residents explained how, instead of cracking down en masse in daytime, the military had its spies photograph protesters, then arrest them after dark. To make sure that no one could witness state brutality, it imposed curfews and shut down electricity during night arrests.

These strategies are now being updated

In 2021, the Tatmadaw is adapting its tactics to deal with social media platforms, especially Facebook, which now reaches more than half of the country’s population. People talk about how Facebook and Twitter enabled mass protests during the Arab Spring and other times, but dictators, too, have learned how to harness social media to influence public opinion at scale.

Myanmar is a pioneer of these techniques. During the 2017 Rohingya crisis and recent 2020 general election, evidence suggests that the Tatmadaw coordinated hundreds of fake social media accounts to spread hate speech and provoke violence against ethnic and religious minorities, incite mass condemnation of the independent press and promote allegations of election frauds. As it seeks to suppress online resistance campaigns in 2021, the Tatmadaw is likely to counter-mobilize against dissidents by spreading disinformation online or selectively blocking Internet access.

It is plausible that the military will use fake social media accounts again, this time to monitor, infiltrate and spread disinformation against online groups and campaigns against the February coup. Social media platforms have a hard time regulating account registration and ensuring that people present themselves truthfully, instead putting the burden on individual users to detect falsehoods. But it’s also increasingly difficult for ordinary civilians to decide what to believe, given that Tatmadaw agents have become adept at spreading false information and impersonating local community members since 2017.

And the Tatmadaw may move further in selectively blocking Internet access across the country to impede online mobilizations for anti-coup protests. In the week since the coup, it has first blocked Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and then intermittently disrupted both Internet and phone connections.

Civil society groups still have some options

The communication disruptions present organizers of Myanmar’s civil disobedience and protest campaigns with some real challenges. These groups are likely to want to use various channels to raise public awareness about potential disinformation campaigns and encourage Internet users to verify news with trusted media and official sources. If they want to blunt the regime’s repression, they’re also going to have to stay alert to the possibility of infiltration of military agents — both online and offline — while providing protesters with guidance to protect their personal and digital safety.

With Aung San Suu Kyi and many other prominent civilian leaders still under detention and demonstrations growing across towns and cities, there is one ultimate weapon left in the Tatmadaw’s toolbox: large-scale violent crackdown. The military has massacred protesters in the past — and got away with it. Knowing the world is watching might make military leaders think twice this time.

Van Tran, a researcher on social movements in Myanmar, recently received her PhD in political science from Cornell University. Follow her on Twitter @vmtran.

Note: Updated Oct. 6, 2023.