Recently, U.S. Sen. Robert Menendez was charged with accepting bribes, the second time in the last decade that the New Jersey Democrat has faced a federal corruption indictment.

The indictment generated a flood of media attention. No wonder, given prosecutors’ allegations that Menendez and his wife accepted a Mercedes, cash, and gold bars in exchange for wielding political influence to help New Jersey business owners and the government of Egypt.

From the perspective of democratic accountability, the widespread coverage is good. When elected officials are credibly accused of wrongdoing, the press should vigorously report on it, giving voters and other leaders a chance to evaluate the allegations. Since the news broke, many fellow Democrats have called on Menendez to resign – a suggestion he pointedly refused in denying the charges last Monday and again Thursday at a private meeting of Senate Democrats.

But for scandals involving statewide or congressional officials, such high-profile media coverage is rare. My ongoing research suggests that the amount of reporting about scandals has been declining over time, likely because of the devastation of local media. That decline may also help explain why local news now plays a weaker role in holding elected officials accountable for the positions they take and what they do in office.

The penalty for scandals may be waning

A long line of political science research shows that scandals are bad for politicians. Studies of the House banking scandal in the 1990s, for instance, found that incumbents accused of writing bad checks were more likely to retire or face strong challengers than other members of Congress. A decade ago, political scientist Scott Basinger showed that congressional officials implicated in a scandal were more likely to retire, be defeated, or lose vote share in their next election. Scandals aren’t fatal, but they make it harder for politicians to survive.

But the penalty for political scandal may be declining. And this isn’t just about Donald Trump. In a study of congressional scandals dating back to 1980, Brian Hamel and Michael Miller found that since 1994 voters have become less likely to punish officials embroiled in a scandal. And in fact, scandals may now even help incumbents raise more in campaign donations.

One obvious explanation is partisanship: Not only do more electoral districts now heavily favor one party, but voters are willing to tolerate bad behavior from their own party’s candidates rather than defect and support the opposition, something Brandon Rottinghaus noted in Good Authority’s former incarnation. That all can limit the electoral fallout for a scandal-plagued incumbent.

The demise of local news may be to blame

But changes to the media environment might also matter. As Jennifer Lawless and I describe in our book News Hole, state and local newspapers have been cutting their staff for two decades. This has reduced coverage of local politics, which includes the actions – and potentially misdeeds – of state officials and members of Congress. Moreover, fewer Americans now get their news from the local media outlets that report on these officials.

This is important, because how much voters hear about scandals could affect whether elected officials keep their jobs. If newspapers have become less likely to report on incumbents’ misbehavior, and fewer voters see that coverage even when it appears, then scandal-plagued officials may be less worried about getting caught.

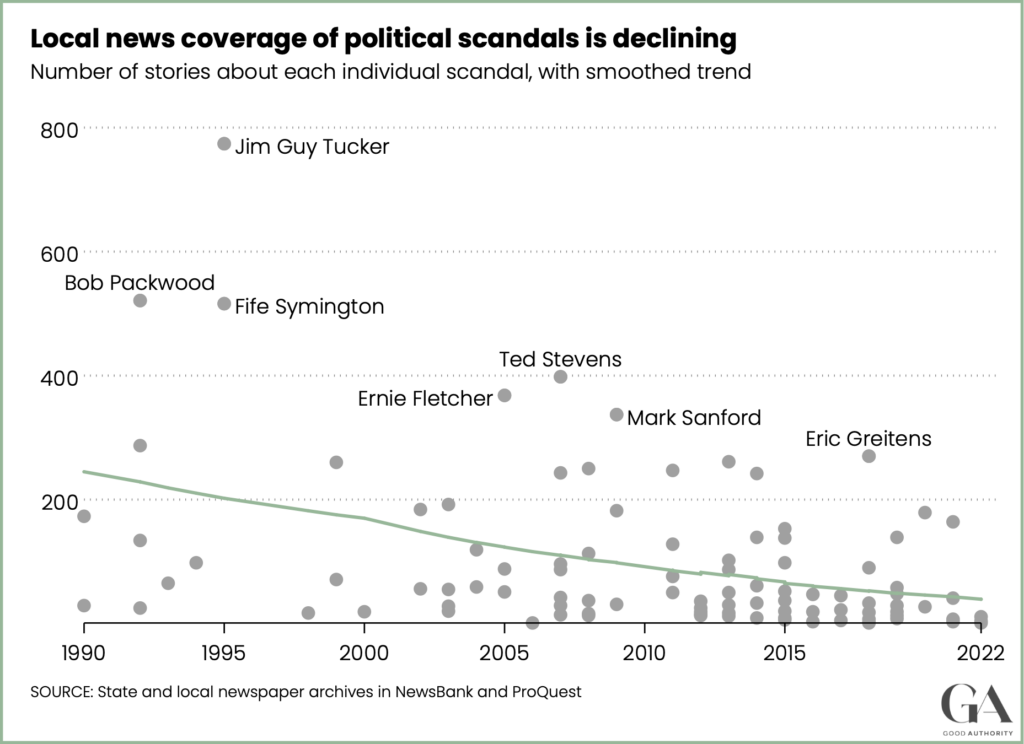

My ongoing research finds that coverage of political scandals at the state and local level has indeed decreased over time. Drawing on a database compiled by 538’s Nathaniel Rakich, I collected data on local media coverage of more than 200 scandals between 1990 and 2022. These include corruption investigations like the 2005 case involving former Rep. William Jefferson (D-La.), in which investigators found cash stashed in a Pillsbury pie crust box in a freezer. They also include sexual misconduct, campaign finance violations, criminal behavior, and other episodes in which officials were “credibly accused of illegal or unethical activity.”

For each scandal, I identified the relevant local newspaper covering each politician. For statewide officials, I chose the largest paper in their state. For House members, I looked at the largest newspaper in their district. Then, using the NewsBank and ProQuest databases, I identified how many stories were published about each scandal.

The graph below plots the trend for statewide officials, including a smoothed lowess line. (To make the graph more readable, it omits the 1,690 stories about the 2013-2014 Bridgegate scandal involving then-New Jersey Governor Chris Christie – more than twice as many as any other scandal. But the overall trend holds despite the Bridgegate outlier.) For instance, The Oregonian in Portland published 521 stories about the 1992 sexual misconduct scandal involving Sen. Bob Packwood (R-Ore.). By comparison, in 2018 reports about Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens’ alleged extramarital affair and blackmail effort saw the St. Louis Post-Dispatch publish 270 stories.

As each decade has gone by, newspapers have published fewer scandal stories. In the 1990s, a statewide scandal on average generated 228 stories. In the first decade of the 2000s, it was 112. But since 2010, that number is down to 88, which includes even the stratospheric Bridgegate coverage. Looking just at scandals since 2015, the average number of stories has fallen to 49.

The data show the same recent dropoff for House scandals, although the coverage peak came in the early 2000s. Before 2010, a House scandal generated 77 stories on average in the district’s largest local newspaper. Since then, it has fallen to just 23.

These findings are not the result of changes in the type of scandals politicians have been embroiled in. For instance, regardless of whether the scandal involves corruption allegations, sexual misconduct, or political missteps like ethics or campaign finance charges, the patterns are the same: significantly less coverage in the last decade.

That development is consistent with the widespread retrenchment in local newsrooms. With smaller audiences, less revenue, and fewer reporters, newspapers simply can’t sustain coverage of what would otherwise be attractive and newsworthy stories. The result, journalist Mary Ellen Klas has written, is that politicians know they can “just wait us out – until our overstretched staff [leaves] to chase the next big story.”

How the decay of local media affects democracy

The consequences for democratic accountability are evident in recent research into whether local media coverage makes it harder for candidates with extreme ideological positions to win seats in Congress.

In an analysis from 1990 through 2014, political scientists Brandice Canes-Wrone and Michael Kistner focus on the level of overlap between congressional districts and newspaper circulation areas. Prior research has found that in places with more overlap, newspapers devote more coverage to members of Congress (and congressional campaigns). Consequently, voters in those places tend to be better informed. In theory, then, more media coverage should make it harder for candidates who are ideologically out of step with voters to win elections.

Indeed, Canes-Wrone and Kistner’s analysis shows that the more district-newspaper overlap there is, the fewer votes extreme candidates receive. But since 2005, that relationship has weakened significantly, especially for congressional challengers. Now, even in places with a significant media presence, the penalty for adopting extreme positions is substantially less than it was in an earlier era.

These findings suggest that the dramatic changes to the media environment in recent decades have taken the teeth out of the local media’s accountability function. Except in rare cases where irresistible details of a story – say, gold bullion – sustain the media’s interest, state and local officials may have fewer incentives to steer clear of scandals and to adopt positions that reflect their constituents’ preferences.