Not long ago, Liz Cheney was a rising star in the conservative movement. Now she may not survive her primary. Based on her voting record, Cheney is approximately as conservative as Devin Nunes and Kevin McCarthy. And yet many other Republicans now call her a “RINO” (Republican in name 0nly) for supporting Donald Trump’s impeachment and helping to lead the Jan. 6 investigation.

In historical context, this is puzzling. The few Americans who vote in midterm congressional primaries — roughly 20 percent of eligible voters — are typically the most politically engaged, knowledgeable and ideologically committed members of the electorate. Why would these voters, who traditionally reward ideological purity, favor loyalty to Trump over candidates like Cheney, whose record seems to align so much better with conservative principles?

The answer lies in a misunderstanding of the nature of ideology. Political scientists typically associate having an ideology with being politically “sophisticated”: holding consistent views derived from principles. But recent research suggests that ideology among both conservatives and liberals has less to do with shared principles than 1) shared identities, 2) shared norms about what a “good” liberal or conservative ought to believe, and 3) motivation to conform to those norms.

This has vital implications for democracy. Because political leaders’ visibility lets them influence group norms, they can pressure conformity from among the very citizens tasked with holding them accountable.

Following the leader vs. thinking for oneself

The association between ideology and what political scientists call “sophistication” has been reinforced by decades of political science research. Because only a small fraction of Americans with self-described ideologies hold the policy positions they supposedly ought to hold as members of that ideological group, those who actually do appear sophisticated.

For the majority of Americans, the disconnect between their ideological self-description and their stated opinions limits the usefulness of ideology as a concept for understanding public opinion, leading some to call self-described ideology “relatively meaningless.”

Our research contends that although ideological consistency need not indicate sophistication, it is nonetheless vital to understand — because self-reported ideology is an identity, not a worldview. People look to other ideological group members to see what it means to be liberal or conservative. For instance, in 2010, political scientists Ariel Malka and Yphtach Lelkes (one of this post’s authors) found that liberals and conservatives tend to follow the leader, adopting the issue positions of prominent liberals and conservatives.

What does this tell us about the nature of ideology? In recent research, soon to be published, the other three of this post’s authors — Eric Groenendyk, Erik Kimbrough and Mark Pickup — surveyed a sample of Americans from the 2018 YouGov panel, which is opt-in, but with targeted sampling used to build a panel that matches the census on gender, age, education, ideology, region and voter registration. Their analyses focus on the 961 respondents who identified themselves as liberal or conservative.

Like many surveys, they asked respondents to report their beliefs on a variety of issues. What distinguished this study was that it also measured ideological group norms by asking self-identified liberals and conservatives what they believed others in their group expected them to believe. To discourage respondents from projecting their own beliefs onto their group’s norms, they offered $2 to respondents who accurately guessed their group’s most common answer on a randomly chosen question. They found that, on most issues, a clear majority agreed on what the group was supposed to believe, varying slightly across issues.

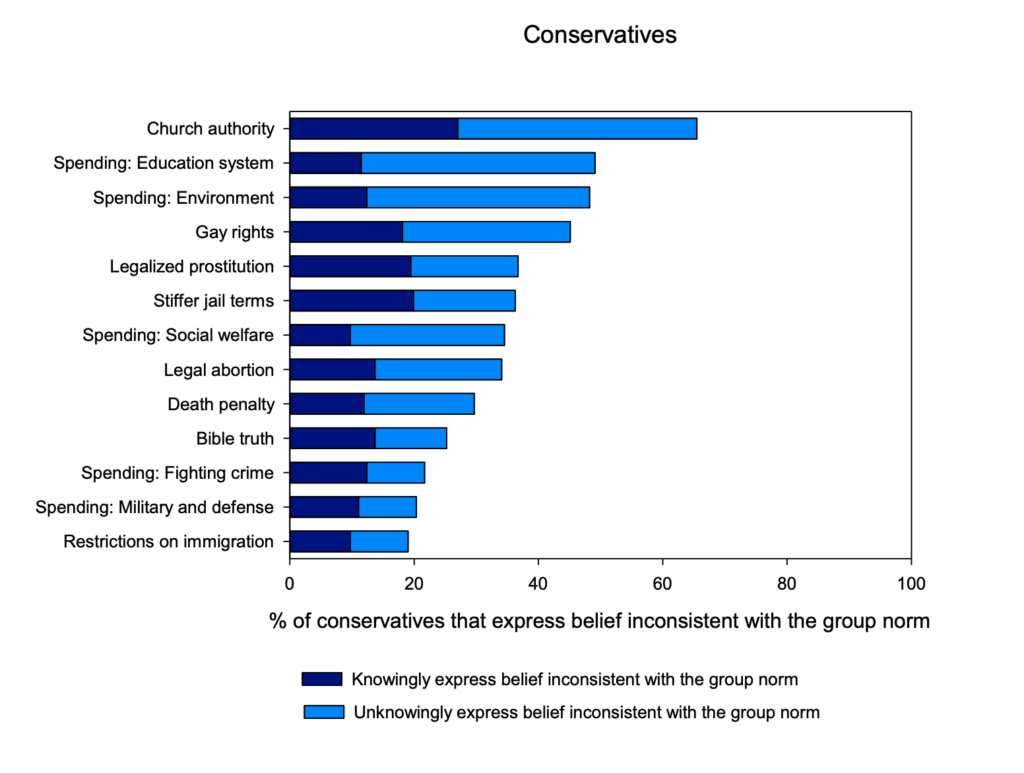

In the figures below, respondents are scored as ideologically consistent for each issue on which their own view corresponded to their group’s norm, and as ideologically inconsistent where it did not. You can see the share of respondents whose own positions differ from their group’s norm on each issue, broken down by whether they didn’t know the consensus position or knowingly took a different position.

For example, of the 19 percent of conservatives who differ from the conservative norm opposing increased immigration, about half knew they were breaking away from the norms. Likewise, around half the liberals who differed from their group’s position on education, health care and environmental spending knew they were defying liberal norms.

This suggests that many individuals previously characterized as lacking political sophistication, due to their ideologically inconsistent opinions, were actually just thinking for themselves. Given this, we might worry that ideological consistency of the kind that political scientists have lionized as sophistication is partly a product of conformity.

Sophistication or conformity?

To distinguish sophistication from mere conformity, Groenendyk, Kimbrough and Pickup embedded an experiment within this survey. In the survey data reported so far, we asked respondents first about their own view and second about their group’s ideological norms. With a new group, we asked the same questions in the opposite order. Asking first about norms makes people consider those norms when they report their own views, increasing the pressure to conform.

Among both liberals and conservatives, thinking first about group norms led them to report personal views that were closer to their understanding of their group’s norm. Thus, although their beliefs look more “sophisticated” in the sense described above, in fact, this increased consistency is actually conformity.

Changing ideological norms

When Donald Trump won the 2016 Republican nomination, he became the new conservative standard-bearer. Conservative publications like the National Review and Weekly Standard and conservative opponents like Ted Cruz argued that Trump was unmoored from conservative principles. Since then, the National Review has softened its stance, and Cruz has fallen in line.

Those who have refused to conform to the new norm, like Liz Cheney and the Weekly Standard, are being forced out of office and out of business, as Trump’s “National Conservatism” becomes the new conservatism. Why punish disloyalty to Trump rather than rewarding commitment to principles? It appears it is not just Trump who is unmoored from principles, but perhaps ideology itself.

Eric Groenendyk (@EricGroenendyk) is a professor of political science at the University of Memphis and author of “Competing Motives in the Partisan Mind” (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Erik O. Kimbrough (@bemusement) is a professor of economics at the Smith Institute for Political Economy and Philosophy at Chapman University.

Yphtach Lelkes (@ylelkes) is an associate professor at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania.

Mark Pickup (@mapickup) is a professor of political science at Simon Fraser University.