Editors’ note: In this archival piece from 2018, Good Authority editor Jeremy Wallace explains why changing the constitution to allow President Xi Jinping to continue to lead China indefinitely is problematic. This analysis was originally published in the Washington Post on February 27, 2018.

In early 2018, China’s constitution is set to drop the two-term limit for president, allowing Xi Jinping to extend his rule beyond 2023. Here are three things to know about Xi’s increasingly personal rule:

1. Xi has broken a decades-old norm of collective rule

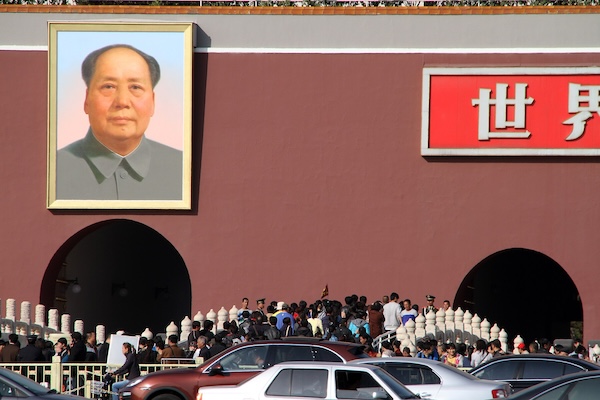

China’s last “leader for life” was Chairman Mao Zedong, who ruled China from 1949 until his death in 1976. Following the disastrous chaos of the Cultural Revolution that left hundreds of thousands dead, China’s communist leadership put in place rules and norms to support collective rather than personal leadership.

Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese leader who spearheaded reform after Mao passed, spoke against personal rule in 1980: “Over-concentration of power is liable to give rise to arbitrary rule by individuals at the expense of collective leadership.” Most China watchers expected Xi to follow his predecessor Hu Jintao’s example and rule for only 10 years, but now there is consensus that Xi will stay on after this period.

In 2003, describing Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s personalization of power, political scientist Dan Slater wrote that prospective personalists had three mechanisms at their disposal: “packing, rigging, and circumventing.”

In China, Xi packed key government positions with his supporters while purging rivals. He also created significant new organizations, such as small leadership groups, that he controls to circumvent rival power centers. With these latest constitutional changes, he has rigged the game in his favor, too. The Chinese Communist Party is a massive and powerful organization, but increasingly it is an institution ruled by just one man, Xi Jinping.

2. The personalization of power is dangerous

Changing the constitution to keep the leader in office is precisely the kind of change that scholars use to gauge rising or falling personalism. Here’s why political scientists see the personalization of power as a dangerous development.

First, personalism makes calamitous mistakes more likely, as policy follows the whims of an individual. Think Nicolae Ceaușescu’s demographic policies in Romania, Saddam Hussein ignoring diplomatic efforts to avoid the first Gulf War – or the famine that resulted from Mao’s Great Leap Forward. Fast forward to the policy errors and flip-flops under Xi’s leadership. In 2015, officials encouraged stock purchases and blamed foreigners when the inevitable sell off occurred. In 2016, a poorly constructed “circuit breaker” designed to halt stock market crashes instead caused them – before being quickly removed.

Second, foreign policy tends to be more conflictual when leaders are strongmen, rather than at the head of political machines. Since Xi came to power in 2013, China’s military has acted with increased assertiveness in contested territorial claims in the East China Sea and South China Sea, as well as its border with India.

Third, increased personalism also undermines the idea of a Chinese governance model. Although another set of proposed constitutional revisions refer to China’s place in a “community with shared future for humanity,” and the country has invested substantially in “soft power” through initiatives such as “One Belt, One Road,” abrupt changes in the structure and institutionalization of power point to deficiencies rather than strengths in the “China Model.”

Similarly, if Xi’s leadership merely uses law as a tool of governance rather than a real constraint on behavior, the international community is likely to view Chinese participation in international legal arrangements with increased skepticism.

3. How should we interpret Xi’s rising personal power?

Well, rulers like to rule, and having the Economist label you the “World’s Most Powerful Man” surely is sweeter than honey.

Beyond this, Xi has initiated a substantial anti-corruption campaign that has gone after tens of thousands of officials at all levels, including retired top leaders such as Zhou Yongkang. Some targets no doubt were Xi rivals, but there is good reason to believe that the Communist Party’s pervasive corruption had become a major source of economic and political risk.

Even if Xi is interested in the party and the broader regime rather than his own aggrandizement, going after top-level retirees broke a norm of exemption. This makes it difficult for Xi to retire, as he could become a target given his family’s wealth – despite their efforts to shed assets.

To be sure, the proposed constitutional revisions do not stop at allowing Xi a third term. They call for inclusion of a reference to “core socialist values,” a “public oath of allegiance to the constitution” for state officials upon assuming office, and for listing a supervision commission as a new state organ.

These changes are evidence that power is centralizing in Beijing – in addition to being concentrated in Xi. Local government officials enjoyed relatively free rein for much of the post-Mao period as long as the economy grew and tax revenue came in. But the central government increasingly is investing in its monitoring capacity and offering a rhetoric of governing morally with a mix of Confucian and Communist Party virtues.

Conflicting interpretations of the centralization and personalization of power are certainly possible. If one sees China as a strong regime, then these moves are reforms to maintain that strength and act simultaneously as a “fix” and a “hedge.”

The government is attempting to fix slowing economic performance while hedging against the possibility of the end of rapid growth with new claims to justify its rule. On the other hand, if one sees a weak Chinese regime, then personalization could be a last-gasp effort to maintain order amid growing popular dissatisfaction, elite divisions and worsening economic conditions.