With its sea of pink pussyhats, the first Women’s March in January 2017 announced that millions of people objected to the newly inaugurated President Trump, and particularly his treatment of women. But some observers criticized it for being overwhelmingly white, despite a leadership group that was primarily women of color, and for failing to pay enough attention to the variety of concerns in its platform, including issues of race, immigration, workers’ rights and environmental justice.

The Women’s March received hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations, coalescing into numerous organizations that have continued to organize and protest since Trump’s swearing-in. But it has faced ongoing criticism, with accusations that include anti-Semitism, a continued focus on white women and more.

In response, the March’s leaders claim that theirs is an “intersectional activism” approach that emphasizes diversity in organizing and advocates for policies that address a wide variety of issues, including discrimination by sex, gender, race, ethnicity, sexuality, class, nationality, disability, religion and other marginalized statuses.

Which is true?

In a new study recently published in the journal Politics, Groups, and Identities, I examine whether the Women’s March has lived up to its stated commitment to intersectional activism. Using evidence from surveys at five Women’s March rallies and four other protest events in Washington in 2018, my findings show that the Women’s March has indeed been successful in mobilizing people who support intersectional activism.

What is the intersectionality controversy about?

At various times in U.S. history, women have mobilized to address issues that matter to large numbers of women. Prominent examples have been the Woman Suffrage Movement and the campaign for the Equal Rights Amendment. Critical race theorists and other scholars have explored that these feminist mobilizations tended to be led by and focus on the concerns of white, middle-class, heterosexual women and neglected the concerns of women of color, the poor and other groups facing discrimination.

When the Women’s March began, some observers warned that the Women’s March could repeat those tendencies. An online chorus pushed for the March to give greater attention to those whose identities as women intersect with other identities that can also face mistreatment — a concept called “intersectionality.”

The march brought women with more diverse racial, religious, and occupational backgrounds into its leadership and pressed the theme of intersectionality at its events and in its platform. Did that work?

How I did my research

One way to determine whether an organization supports a cause is by seeing whether the people who join the organization support that cause. With this in mind, I conducted surveys at a selection of Women’s March events in January 2018, choosing those held in New York, Washington, Lansing, Mich., Las Vegas and Los Angeles. I picked these to try for as broad a representation of the United States as possible within budgetary constraints.

My team and I asked a random sample of participants — selected at each event using a randomized counting technique — about their views on a variety of topics. The key question about intersectional activism was this: “How important is it that the women’s movement center, represent, and empower the perspectives of subgroups of women, such as women of color, LGBTQIA+ women, and low-income women?”

To have a comparison sample, I conducted analogous surveys at four Washington protests on different topics. Two were liberal protests: The People’s March, focused on impeachment, and the March for Our Lives, focused on ending gun violence. The other two were conservative protests: the March for Life, an antiabortion event, and the self-explanatory March for Trump. We used these surveys to see whether the answers we got at the Women’s Marches were similar to or different from attitudes at other protests.

High rates of support for intersectional activism at Women’s Marches

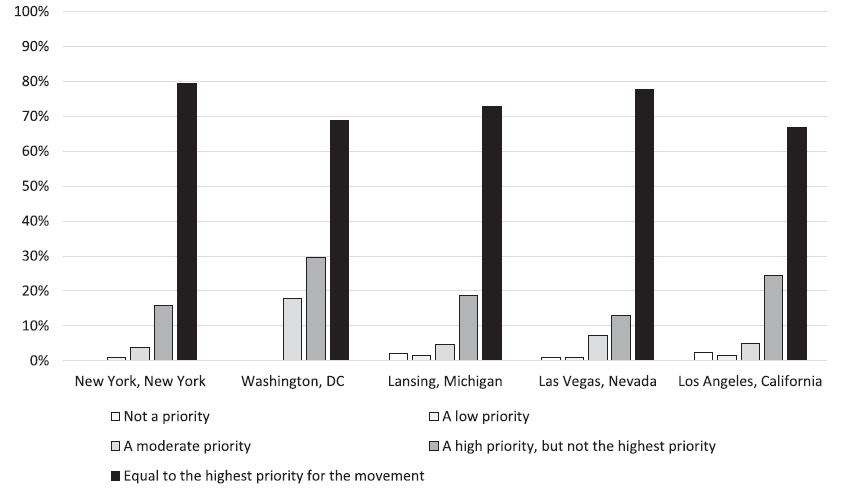

As you can see in the figure below, more than two-thirds of participants surveyed at each of the five Women’s Marches said that the women’s movement should treat the concerns of marginalized women as among the highest priorities for the movement. Most of the rest said that this issue should be a high, but not the highest, priority. This survey question received 521 valid responses.

Participants at the two liberal marches — the People’s March and the March for Our Lives — also reported strong support for intersectional activism: An average of 57 percent told us that it’s equal to the highest priority for the movement. But that average was significantly lower than what we heard at the Women’s Marches, where an average of 73 percent told us it is equal to the highest priority for the movement.

That difference held up even after statistically accounting for demographic differences among the different marches. One could reasonably conclude that the Women’s March has been able to attract participants who are more supportive of intersectional activism than is typical of comparable activists.

What does this mean for the women’s movement?

This finding suggests that the Women’s March has made good on its commitment to intersectional activism. By creating a diverse leadership and talking about intersectionality at events, it has attracted people with a commitment to this cause — or persuaded people in its movement to care more deeply about intersectionality.

To be sure, these findings do not necessarily mean that the Women’s March has transcended the biases with which previous women’s movements have been charged. Saying that one supports intersectional activism is not the same thing as treating issues of poverty, race, immigration and so on, as priorities equal to issues primarily affecting white, middle-class women.

But it does suggest that the Women’s March has made sustained efforts to organize women in a way that involves many different issues, including race, sexuality, class and religion — and that the large majority of its participants embrace those values.

Michael T. Heaney is a research fellow in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Glasgow and an adjunct research professor in the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan. He is the author, with Fabio Rojas, of “Party in the Street: The Antiwar Movement and the Democratic Party after 9/11” (Cambridge University Press, 2015).