In February, Senegalese police officers killed three people and arrested hundreds in a crackdown on protesters against President Macky Sall’s efforts to postpone the presidential election. It’s not the most brutal police repression in recent memory in Africa, compared to police action during elections in Zimbabwe (2023) and Uganda (2021). But the police response in Senegal was heavy-handed – and far from unusual.

The use of excessive force is one of a litany of charges that critics in Africa lay against their police forces, pointing to news media and social media evidence of unprofessional conduct, selective enforcement of the law, unlawful arrests, corruption, and deadly violence.

Against this background, Afrobarometer surveys offer new evidence of how Africans experience and evaluate their police. Data from 39 African countries, collected in face-to-face interviews between late 2021 and mid-2023, highlight widespread perceptions of police misconduct, corruption, and brutality. Africans’ experiences and assessments of the police vary significantly by country, however.

Encounters with the police

Across the 39-country sample, 13% of respondents say they requested police assistance during the previous 12 months. Three times as many respondents (40%) report encountering the police in other situations, such as at a checkpoint or during a traffic stop or an investigation.

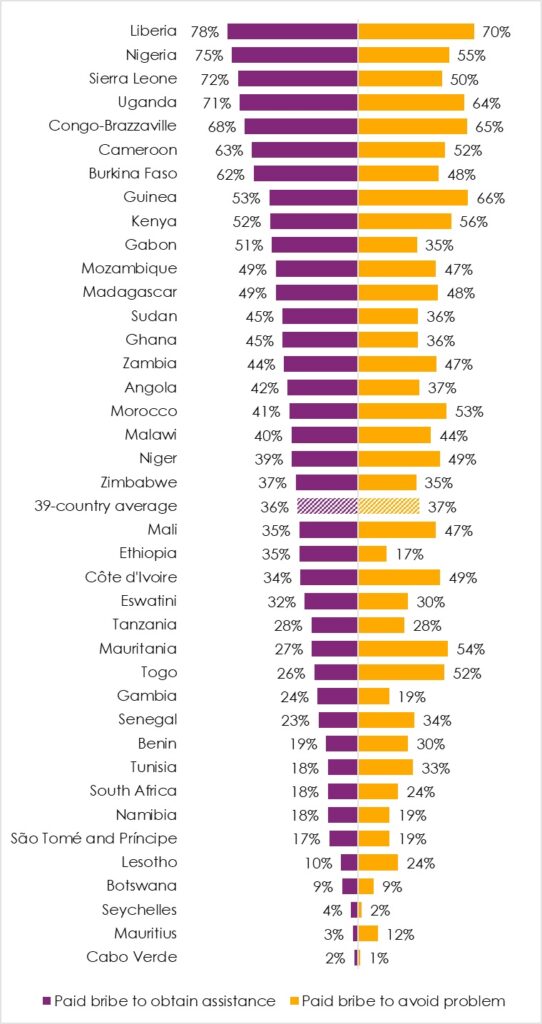

Among those who asked for police assistance, a slim majority (54%) say it was easy to get the help they needed. But 36% say they had to pay a bribe, give a gift, or do a favor to get assistance. This proportion reaches astonishing levels in Liberia (78%), Nigeria (75%), Sierra Leone (72%), and Uganda (71%), as you can see in Figure 1, below.

Similarly, among citizens who encountered the police in other situations, 37% say they had to pay a bribe to avoid a problem. Liberia (70%) again ranks worst, joined by Guinea (66%), Congo-Brazzaville (65%), and Uganda (64%).

Bribery and corruption

Cabo Verde performs best on both counts, with just 1% to 2% reporting having to pay a bribe. Other countries scoring well on this question are Seychelles and Mauritius.

Considering how many Africans report personal experiences with having to bribe the police, it may not be surprising that Africans see the police as more corrupt than civil servants, officials within the presidency, or any other public institutions or leaders the surveys asked about. Almost half (46%) of respondents say that “most” or “all” police officials are corrupt. Another 41% say “some of them” are.

Figure 1: Paid bribe to receive police assistance/avoid problems | 39 African countries | 2021/2023

Police brutality

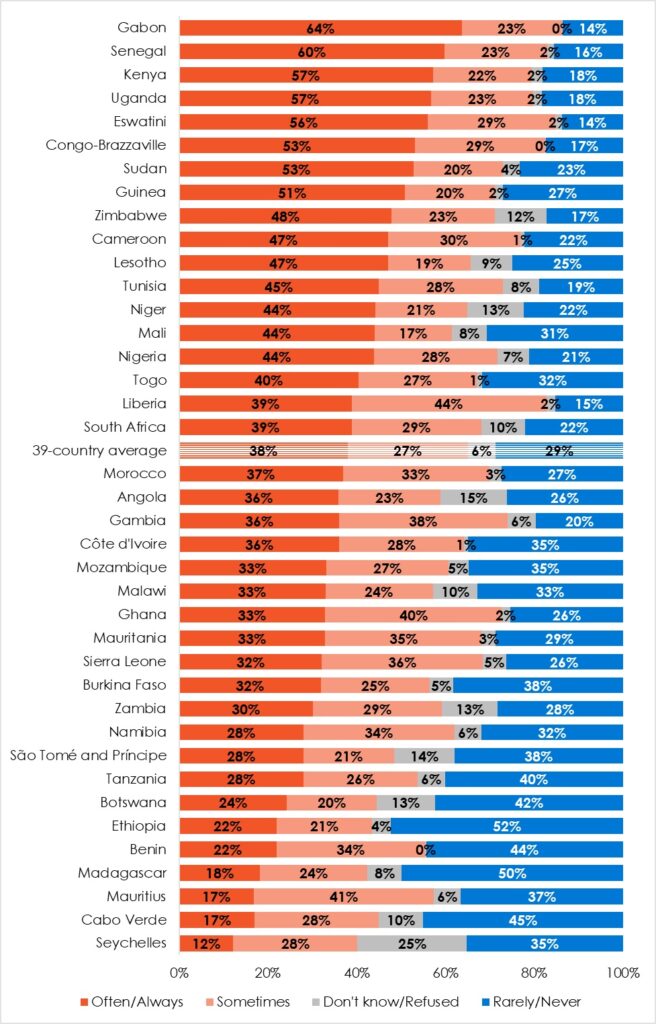

One of the harshest criticisms leveled against some police officers is that they use excessive force in their interactions with the citizenry they are meant to serve and protect. As Figure 2 shows, almost four in 10 Afrobarometer respondents (38%) say the police “often” or “always” use excessive force in managing protests or demonstrations. Another 27% say they “sometimes” do so. The perception of frequent police brutality against protesters is most common in Gabon (64% often/always). And this perception is widespread in several countries that are planning to have national elections this year, including Senegal (60%), Guinea (51%), and Tunisia (45%).

Figure 2: Do police use excessive force during protests? | 39 African countries | 2021/2023

Citizens hold similar views on police treatment of criminal suspects. On average, 42% say the police routinely use excessive force; only 25% think they “rarely” or “never” abuse suspected criminals.

Are the police professional?

On other indicators, the survey data reveal mixed assessments, at best. Only 29% of Africans say the police “rarely” or “never” stop drivers without good reason, and just 36% think they don’t engage in criminal activities.

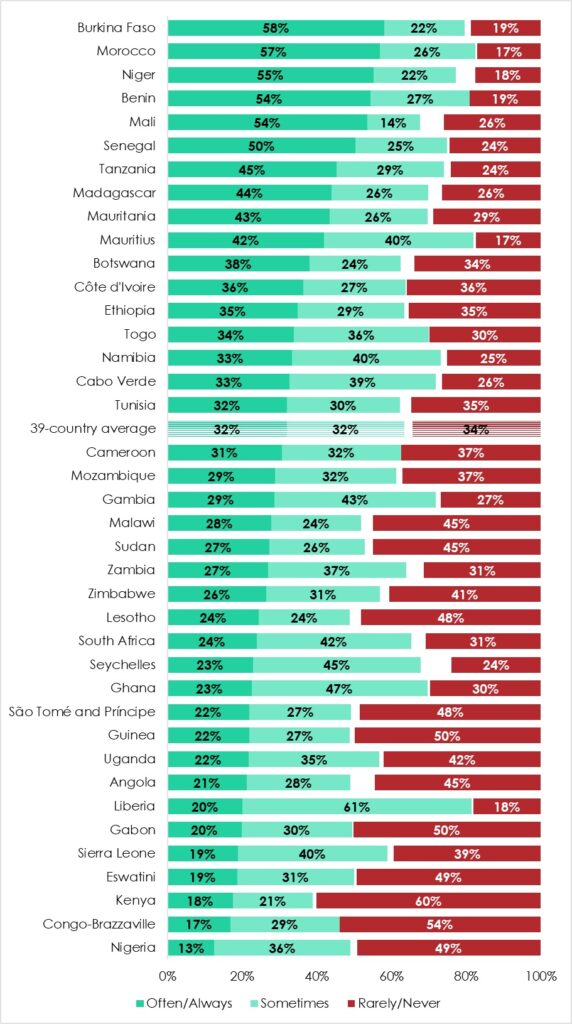

Overall, only one-third (32%) of Africans say the police in their country “often” or “always” operate in a professional manner and respect the rights of all citizens. Just as many (34%) say police “rarely” or “never” do so (Figure 3).

In only six countries do at least half of citizens think their police usually act professionally: Burkina Faso (58%), Morocco (57%), Niger (55%), Benin (54%), Mali (54%), and Senegal (50%). Meanwhile, fewer than one in five respondents agree in Sierra Leone (19%), Eswatini (19%), Kenya (18%), Congo-Brazzaville (17%), and Nigeria (13%).

Figure 3: Do police act professionally and respect citizens’ rights? | 39 African countries | 2021/2023

Police professionalism and trust

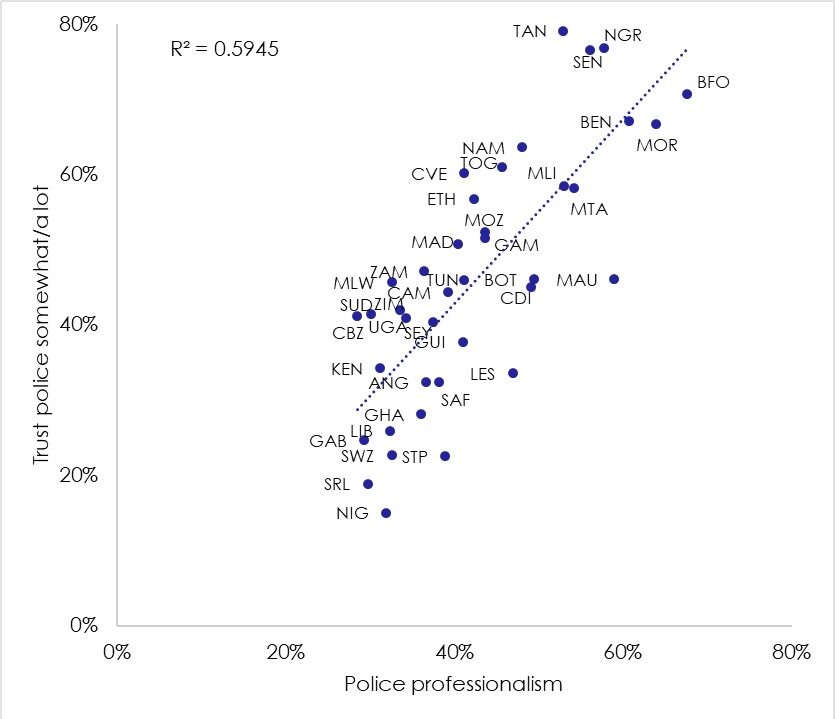

Police professionalism tends to correlate with another essential element of effective police work – public trust. Just as most Africans view their police as lacking in professionalism, fewer than half (46%) trust their police “somewhat” or “a lot.”

The scatter plot below illustrates this relationship. Countries in the lower left record low levels of both perceived professionalism and trust. For example, Nigeria (NIG) scores 32% on professionalism and 15% on trust. As countries’ professionalism scores rise, so do their trust scores (e.g. Burkina Faso – BFO – 68% and 71%). The graph shows no countries in the upper left section because low professionalism never matches up with high public trust. The same goes for the lower right: No country records both high levels of police professionalism and low public trust.

A correlation analysis like this shows that the two factors – professionalism and trust – are associated. The analysis does not suggest which one causes the other. But it seems plausible that professional conduct by the police contributes to public trust, rather than the other way around.

Figure 4: Police professionalism and public trust in police | 39 African countries | 2021/2023

Taken together, our data raise serious questions about the quality of policing on the African continent. These findings highlight notably negative experiences and evaluations of the police in many – but not all – countries. Whether driving down the road or waving a protest banner, citizens’ experience with the police may well depend on where they live.

Matthias Krönke is a researcher in the Afrobarometer Analysis Unit.

Thomas Isbell was formerly a capacity building manager for Afrobarometer.

Makanga Ronald Kakumba is a senior data manager for MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit in Entebbe, Uganda, and a researcher in the Afrobarometer Analysis Unit.