Recently, The Washington Post’s Amy Gardner reported that half the Republicans running for the House, Senate and key statewide offices have either challenged or refused to accept the fact that Joe Biden won the 2020 presidential election. Experts expect most — but not all — of these election deniers to win. If Republicans win the House majority, they would be in position to oversee any election challenges.

So will election-denialist losers challenge the outcome this fall? If they do, Republicans could revive their late-19th-century strategy of disputing electoral outcomes in the House — aiming to flip seats to gain or grow their new majority.

Constitutional basis for disputing elections

The Constitution’s Article I, Section 5, Clause 1 stipulates that “Each House shall be the Judge of the Elections, Returns, and Qualifications of its own Members.” That means if a challenger disputes the results of a House or Senate election, the members of the relevant chamber decide who is duly elected and has a right to the seat.

In other words, Republican losers in House races could try to use the constitutional clause to block the House from seating a Democrat who is state-certified as the winner of the election. If they succeed, they could take that place in the chamber.

How does this work? Within 30 days after a secretary of state or state canvassing board declares an election winner, the “contestant” — the ostensible loser challenging the outcome — must file a “contest,” explaining the grounds for disputing the decision. The contestant has the burden of proof in showing they are entitled to the seat and lost only because of voting irregularities or alleged fraud.

The Committee on House Administration hears disputed election cases. If the committee finds in favor of the contestant, the full House then votes on whether the contestant should be seated instead of the state-declared election winner.

Here’s the historical record

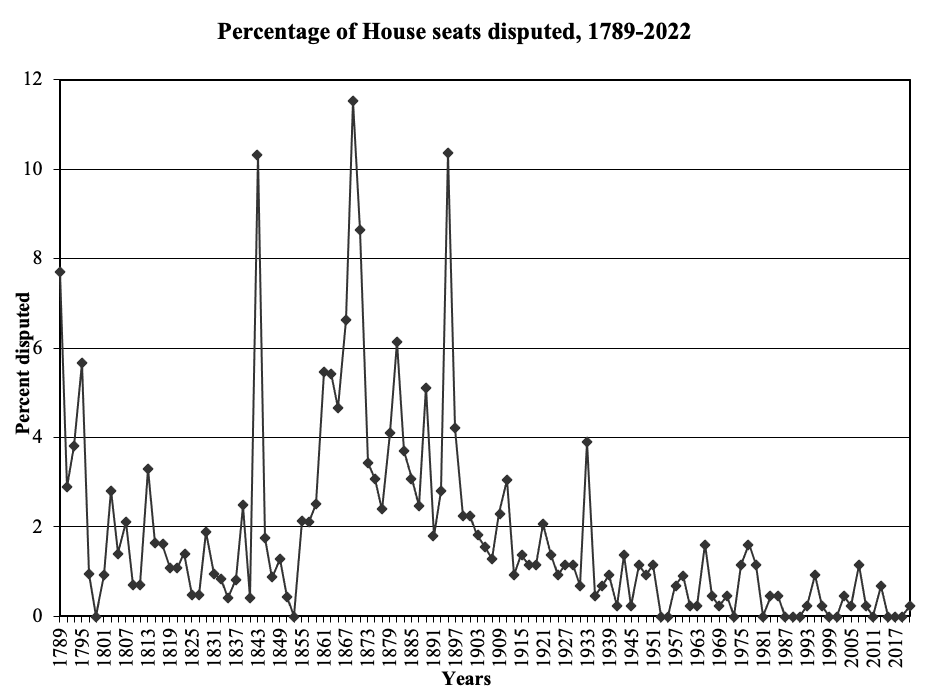

Combing congressional records, I’ve identified 614 disputed-election cases, or an average of more than five per each two-year session of Congress.

But those haven’t been distributed evenly across history. As the figure below illustrates, disputed elections spiked during the late 19th century, after the Civil War and during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age. In three different Congresses, more than 10 percent of House seats were disputed, reaching a high of 11.5 percent in the 41st Congress (1869-71).

This percentage has dropped off considerably. In the past century, the per-Congress average has been less than 1 percent; in many Congresses, no elections were disputed. The most recent dispute came in 2021, when Republican Jim Oberweis unsuccessfully challenged incumbent Democrat Lauren Underwood over who should represent Illinois’ 14th Congressional District. The Committee on House Administration dismissed the election dispute on a voice vote, which was then agreed to by the House.

A tried and true partisan strategy

Why did so many challengers dispute House seats in the late 19th century? In many cases, the loser accused the winner of criminal behavior, such as bribing voters or election officials, illegal ballot alteration and counting, or fraudulent election certification. Many cases also involved accusations that there weren’t enough polling places, that ballots were cast by people not properly registered, and that ballot boxes were treated improperly.

At that time, Congress was fairly evenly divided between the major parties. That meant a few seats swinging either way could decide or strengthen majority control of the House. Republicans brought most of the disputed election cases, largely in the South. Republicans charged that Democrats were using whatever means necessary to prevent African Americans — who had been granted citizenship and voting rights after the Civil War — from voting and selecting representatives who would serve their interests in Congress. Which, of course, was often true.

GOP leaders actively encouraged their candidates to dispute elections, to counter Democrats’ electoral misbehavior. For example, in the 41st Congress (1869-71), the Republican majority ended up flipping 10 seats — half in the South — into the GOP column through election disputes.

By the 44th Congress (1875-77), Democrats had taken control of the House and most state governments in the South. The GOP’s Reconstruction efforts would crumble completely shortly thereafter. Republicans were nonetheless intent on maintaining a partisan foothold in the South. The next five times that the Republicans controlled the House, they boosted their majority by disputing elections in the South and deciding them in their own favor. Of the 58 Southern seats that the Republicans controlled during these five Congresses, 20 (or 34.5 percent) came from election disputes.

Why parties stopped disputing elections

But by 1900, disputed elections had declined considerably. They were rare during much of the 20th century and have been very uncommon more recently. Why?

First, the South — which had hosted most of the election disputes — ceased to be a partisan battleground. Once Southern states had disenfranchised almost all their Black voters by law, effective by the first decade of the 20th century, Democrats firmly controlled the South.

Second, literacy rates increased and — with radio and television — media coverage expanded. By the early 20th century, the populace was better informed, requiring party leaders to better justify any election dispute because such challenges otherwise were overruling the voters’ decisions.

Third, voting became secret, and voting technology improved, making it harder to commit outright election fraud.

Will Republicans dust off the old playbook?

So will today’s Republicans once again use claims of electoral fraud or irregularities to revive the use of disputed elections as a political strategy?

Of course, the United States is in a very different era; the explicit racism and routine political violence that drove late-19th-century election disputes are a thing of the past. Yet the raw materials of a political and partisan strategy to revive disputed-election cases are in place. Political figures — mostly on the right — are routinely charging election fraud and irregularities. Narrow partisan majorities battle over control of Congress. And the country is highly polarized politically.

If Republicans gain control of the House, they would have history — and congressional rules — on their side in pursuing such a strategy.

And if Republicans were to hold together as a House voting bloc, they could successfully “flip” some disputed House seats into the GOP column.

Jeffery A. Jenkins (@jaj7d) is a provost professor of public policy, political science and law and director of the Political Institutions and Political Economy (PIPE) Collaborative at the University of Southern California’s Sol Price School of Public Policy. He is the co-author of two recent books: “Republican Party Politics and the American South, 1865-1968” (Cambridge University Press, 2020) and “Congress and the First Civil Rights Era, 1861-1918” (University of Chicago Press, 2021).