Hostage situations have been on the rise around the world in recent years. From the October 2023 mass kidnapping by Hamas to the rise in hostage diplomacy by Russia and Iran, hostage-taking violence plays an enormous role in international and domestic politics. What is hostage taking, and why does it matter?

What is hostage taking, exactly?

Hostage taking is conditional detention: taking and holding a human captive to coerce someone else to change their behavior.

In 1979, the U.N.’s International Convention against the taking of hostages defined hostage taking as detaining someone “in order to compel a third party, namely, a State, an international governmental organisation, a natural or juridical person, or a group of persons to do or to abstain from doing any act as an explicit or implicit condition for the release of the hostage.”

Hostage taking is a war crime. Over the past 60 years, perpetrators have used three primary forms of hostage taking: hijacking, barricades, and kidnapping.

- In a hijacking, the hostage taker commandeers a vehicle – an airplane, train, car, or even a cruise ship – and brings passengers to a new location, like the 1970 Dawson’s Field hijackings in Jordan or the 1976 hijacking of Air France flight 139, which was diverted to Uganda.

- In a barricade or barrier-siege incident, the hostage taker locks down a building and holds captives inside, like the 1979 Iran hostage crisis or the 1996 siege at the Japanese embassy in Peru.

- A kidnapping is an abduction. The hostage taker brings hostages to a new, often unknown, location, like the 2006 kidnapping of Colombian politician Ingrid Betancourt or the 2009 Taliban kidnapping of Bowe Bergdahl.

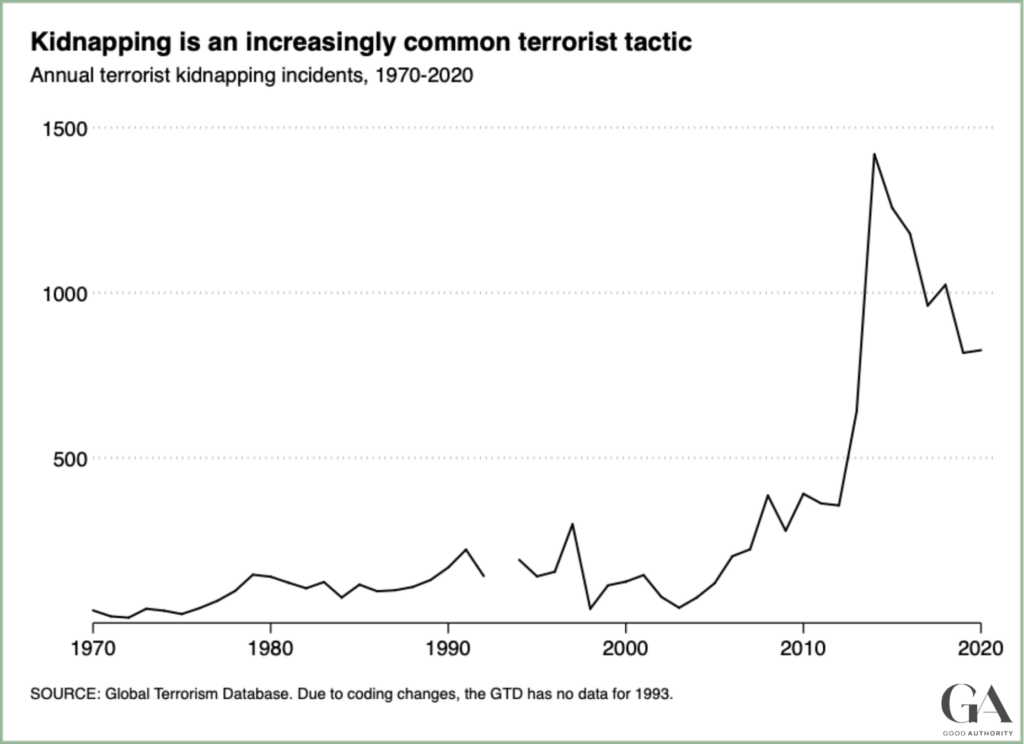

Kidnapping is by far the most common form of hostage-taking violence. Though non-lethal violence statistics are underreported and biased, all indications suggest that kidnapping has increased during the last two decades, as shown in this figure.

Hostage diplomacy is the latest trend

The past few years have seen a surge in a new form of hostage-taking violence: hostage diplomacy. That’s when governments use their criminal justice systems to hold foreigners hostage, in the expectation of political or economic gain.

For this emerging form of hostage-taking violence, the terminology hasn’t been fully settled. Some, including the U.K. government, refer to this as “state-led hostage taking.” The U.S. government calls American victims “wrongfully detained,” while the Canadian government prefers the U.N. term “arbitrary detention” and has authored a Declaration Against Arbitrary Detention in State-to-State Relations. All these terms mean the detention of foreigners by one country’s government in order to coerce concessions from the detainees’ governments.

Why hostage taking matters for politics

Whether it takes place within or across national borders, hostage taking has a direct impact on international and domestic politics.

Hostage taking is a quintessential example of coercion: using threats of force to change behavior. The hostage taker promises to impose pain (by killing or continuing to hold the hostage) if – and only if – the target does not cooperate.

Whether in the “Global War on Terror” or conflict between powerful states, hostage taking is an asymmetric tool. This is a tactic that weaker parties can use to gain leverage on their more powerful adversaries. Still, most hostage-taking violence happens within national borders as a frequent component of civil war, criminal extortion, and piracy.

Because of the pressure that hostage taking puts on the target, hostage taking is relevant for domestic politics. International kidnapping stories receive outsized media attention compared to other foreign policy issues, so voters tend to follow the news about hostage crises.

In the United States, for instance, U.S. presidential approval ratings – and reelection prospects – have suffered in the midst of hostage crises. Failing to recover U.S. embassy personnel held hostage in Iran hurt Pres. Jimmy Carter’s 1980 reelection bid. In 2023, Republicans criticized Pres. Joe Biden’s for agreeing to a controversial prisoner swap with Iran. And Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has faced increasing domestic pressure to change military tactics in Gaza to bring more hostages home.

Research on hostage taking

For decades, game theorists have explored the dynamics of hostage negotiations, as well as determinants of hostage takers’ “success.”

Given its importance to policy debates, researchers have debated the merits of “no concessions” policies. While multiple think tank reports suggest that “no concessions” policies do not deter hostage taking, limited scholarly research suggests that making concessions can incentivize future hostage taking. Private ransom payments, according to one study, may have encouraged jihadist groups to kidnap more Westerners.

A burgeoning literature explores why armed groups kidnap, including my own findings that rebels use kidnapping as tax enforcement. And ideology alone does not predict kidnapping. Territory, networks, and armed-group strength are associated with increased kidnapping frequency.

Democracies are a frequent target

Research suggests that hostage takers – from terrorist groups to autocratic governments – are more likely to target democracies; and stable democracies are more likely to make concessions. Media coverage – which varies widely across cases – is key to these dynamics. Moreover, hostages’ individual characteristics influence not only the outcome of hostage-taking incidents but also public opinion about hostage recovery efforts.

There’s a further aspect to consider. Political economists have explored the role of private markets and kidnap and ransom insurance on kidnapping. Most ransoms are paid not by governments, but by hostages’ families, employers, and the insurance policies that underwrite and stabilize the ransom market.

To date, there has been less political science research on hostage taking than its relevance and significance might suggest. Scholars and students alike may find promising avenues exploring the causes, conduct, and consequences of hostage-taking dynamics.

Related Good Authority posts

- Danielle Gilbert, “Why the Gaza hostage crisis is different.” From October 2023, after Hamas militants attacked Israel and seized over 100 hostages.

- Danielle Gilbert, “Biden’s hostage diplomacy, explained.“ From September 2023, following complex U.S. negotiations to free five U.S. citizens imprisoned in Iran.

- Danielle Gilbert, “Why authoritarian governments take hostages.“ From December 2022, when U.S. basketball star Brittney Griner was freed in a prisoner exchange with Russia.

- Danielle Gilbert, “Brittney Griner was “wrongfully detained. What happens now?“ From May 2022, when the U.S. State Department announced that “the Russian Federation has wrongfully detained U.S. citizen Brittney Griner.”

- Danielle Gilbert, “American missionaries were kidnapped for ransom in Haiti. What happens in these cases?“ From 2021, explaining why seizing foreign hostages is rare in Haiti.

- Danielle Gilbert, “Armed groups allegedly plotted to kidnap Michigan’s governor. Here are 5 things to know about political kidnappings.“ Written following the arrests of 13 men accused of planning to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer in 2020.

Further reading

- Chia-yi Lee, “Democracy, civil liberties, and hostage-taking terrorism,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 50, No. 2 (March 2013).

- Anja Shortland, Kidnap: Inside the Ransom Business (Oxford University Press, 2019).

- Wukki Kim, Justin George, and Todd Sandler, “Introducing Transnational Terrorist Hostage Event (TTHE) Data Set, 1978 to 2018,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 65, Issue 2-3 (February-March 2021).

- Danielle Gilbert, “The Logic of Kidnapping in Civil War: Evidence from Colombia,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 116, No. 4 (November 2022).

- Danielle Gilbert, “The Prisoners Dilemma: America Must Adapt to a New Era of Hostage Taking,” Foreign Affairs (August 2022).