President Trump will soon send the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) to Congress. It won’t pass in the House, though, without support from Democrats who want the new trade deal to include tougher labor and environmental provisions. For example, Rep. Richard E. Neal (D-Mass.), the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, demands that the USMCA include better programs to help American workers hurt by free trade.

Critics such as Neal argue that American free trade agreements fail to address what happens to local communities that are hit by waves of imports and layoffs. While the economic and political consequences of trade-related job losses are well known — lower wages and more support for populist leaders — my research suggests that the impact of free trade is much broader.

In a recently published study, my co-author and I find that trade-related job losses are closely related to spikes in opioid-related overdose deaths. Less-educated males in Appalachia bear the brunt of free trade as well as the opioid epidemic. And as young people look for ways out of communities hurt by trade, enlistment in the U.S. Army also surges. It’s not just that youth are more willing to enlist after trade shocks — the military tends to send more recruiters to these communities.

Trade-related job losses lead to higher levels of opioid addiction

The opioid epidemic now kills roughly 130 people in the United States every day. While this is a national public health emergency, less-educated white men in Appalachia have been particularly harmed.

In 2015, the overdose mortality rate in Appalachia was 65 percent higher than the rest of the country. Less-educated white males suffer overdose deaths at such a high rate that it has lowered their overall life expectancy.

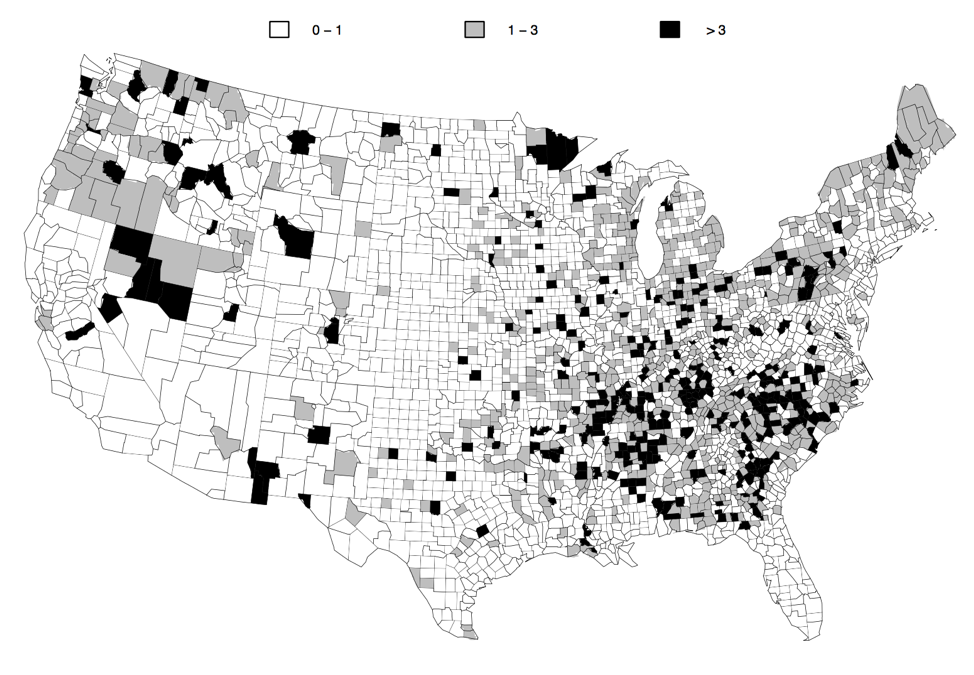

As can be seen in the figure above, Appalachia has the highest rate of trade-related job loss in the country. And trade puts downward pressure on the wages and job prospects of less-educated manufacturing workers, the majority of which are white men.

Job loss generally increases the risk of depression and drug misuse. Since jobs lost from trade are relatively “good” manufacturing jobs — offering better wages, benefits, and higher unionization rates than the rest of the private sector — it may be even more difficult for workers to adjust after layoffs. Worse still, the risk of drug use has significantly increased with the introduction of fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, into heroin markets around the United States.

In a recently published paper, Simeon Kimmel and I explored the nationwide relationship between free trade and the opioid epidemic. We found that 1,000 trade-related job losses in a given locality were associated with a 2.7 percent increase in opioid-related overdose deaths. When fentanyl was present in the local heroin supply, however, the same size trade shock was associated with an 11.3 percent increase in such overdose deaths.

People go into the army — since they don’t have many other options

Since the mid-1990s, free trade has also steadily sent Americans into the military. Trade-related job losses reduce the economic and educational opportunities available to unskilled workers and therefore increase the supply of potential military recruits. Demand for recruits also increases, as the U.S. government responds to these economic shocks by increasing recruitment efforts and enlistment goals in trade-affected counties.

Hickory, N.C., an Appalachian city once known as the “furniture capital of the world,” suffered 11,000 trade-related job losses between 1996 and 2010. In the face of these trade shocks, enlistment in the U.S. Army quadrupled for the local county.

I spoke with a local high school ROTC leader, who explained that students “will try to join the military after high school because they’ve tried the job market, they’ve tried going to college and couldn’t go. … Very few of them are joining the military for patriotic reasons.”

A high school guidance counselor in Hickory told me that before the trade shocks, recruiters would visit their school once a year. Now, military recruiters come multiple times a week and eat lunch with students in the cafeteria. The counselor lamented, “I’m not sure how many states and counties around the country allow just a constant flow of military recruiters in.”

These dynamics spread far beyond the closed furniture mills of North Carolina. I filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the Defense Department and analyzed data from around the United States from 1996 through 2010. The study found that a shock of 1,000 trade-related job losses was associated with a 33 percent increase in Army enlistment in the average county.

U.S. policies do not focus on these problems

With the 2020 presidential election approaching, there is a growing bipartisan consensus in favor of trade protection and government intervention into markets. However, tariffs will not have direct benefits for the communities that have already suffered trade-related job losses. And revised trade agreements such as the USMCA — with their lack of compensation for trade losers — continue to overlook the broader social consequences of free trade.

Adam Dean is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at George Washington University and the author of “From Conflict to Coalition: Profit-Sharing Institutions and the Political Economy of Trade” (Cambridge University Press).