It took a while, but people have finally read past the first section of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. You won’t believe what they found! (Yes, Good Authority is already resorting to clickbait. But Good Clickbait.)

The 14th amendment was ratified in 1868, as part of an effort to redefine the post-Civil War United States. The 13th Amendment barred slavery; the 15th ensured those (at the time, men) of any race could vote. The first section of the 14th sought to provide state and national citizenship rights and equal protection under the law to, as law professor Garrett Epps has written, a newly expansive definition of Americans, including former slaves and immigrants.

At the same time the 14th Amendment addressed some other leftover business from the Civil War. Section 2 says congressional representation can be reduced for states where suffrage is “denied… or in any way abridged,” a clause some progressives think should be invoked in current debates over election regulations they say are tantamount to voter suppression. As we’ve learned in recent years during a series of showdowns over the statutory debt ceiling, Section 4 demands that “the validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, … shall not be questioned.”

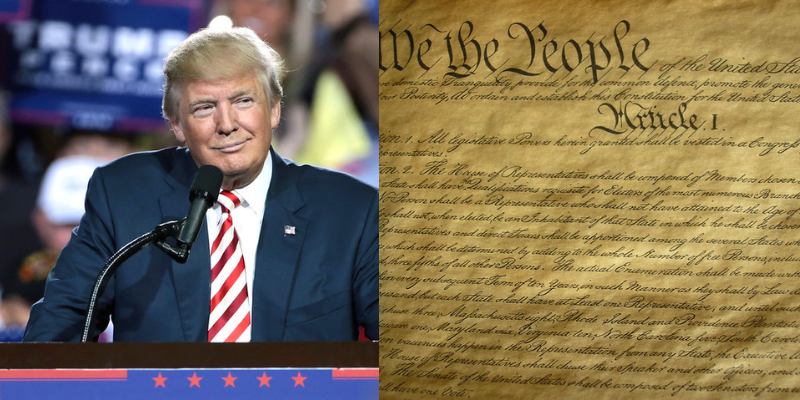

Is Trump ineligible for office because he “engaged in insurrection or rebellion”?

But at the moment it’s Section 3 in the spotlight. This part of the amendment took aim at former government officials who had “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” against “the Constitution of the United States,” preventing them from returning to “any office, civil or military,” state or federal, unless forgiven by a two-thirds vote of Congress. The immediate targets in 1868, of course, were those who had joined the Confederate cause in the Civil War. But should that language now apply to Donald Trump? Maybe so. According to retired judge J. Michael Luttig and law professor Laurence Tribe, “the former president’s efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election, and the resulting attack on the U.S. Capitol, place him squarely within the ambit of the disqualification clause, and he is therefore ineligible to serve as president ever again.”

That argument has been buttressed – and attacked – at length in law journals. (Nothing is not “at length” in law journals.) But now it has moved from theory to potential practice. First, election officials around the country were lobbied to omit Trump from their states’ 2024 ballots. On a bipartisan basis, they demurred, since the high-stakes call on the amendment’s relevance requires a definition of “insurrection,” of what it is to have “engaged” in it, and of whether the amendment’s language applies to the presidency in the first place. “Not our job!” desperately (if metaphorically) shouted various secretaries of states. “It should go to court!”

It turns out the courts don’t really want to deal with it either. In New Hampshire and Florida, federal judges decided those bringing the case against Trump did not have standing to bring the complaint in the first place. In Michigan, a state judge decided the definition of candidate eligibility under Section 3 was a “political question” – judgespeak for “not my problem.” In Minnesota, the reasoning was more like “not yet my problem.” The state supreme court there held that even if Trump were ineligible to become president, the Republican Party could still decide (however pointlessly) to make him its nominee. As such the case was not “ripe” for decision until linked to the general election that would actually place the hypothetically ineligible candidate in office.

One Colorado judge said yes, Trump is an insurrectionist. And yet …

Late last week, though, Colorado district court judge Sarah Wallace took a different approach. In a long (102 page), substantive opinion, she ruled that Trump was in fact guilty of insurrection under the terms of the 14th Amendment – and, indeed, “that the events on and around January 6, 2021, easily satisfy” the definition of that term.

And yet Trump’s camp hailed the decision. This is because despite dozens of pages affirming his engagement in insurrection, Trump won the case, and so he remains on the ballot. Having ruled that an officer of the United States who did what Trump did would be ineligible to serve as an officer of the United States, the judge chose a different door: that Trump, as president, was not actually an officer of the United States.

As strange as this seems, that decision closely tracks an established strand of reasoning flowing from the less-than-crystalline text of Section 3. That text lists a variety of offices which an insurrectionist might have held, and for which he would later be ineligible. But the presidency and vice presidency are never mentioned specifically, even though electors for those posts are. So are members of Congress. As a result, to be covered by this language, the presidency must be included within the catch-all term “officer of the United States.”

Does the omission mean the framers of the amendment meant to exclude the president? The wording is either imprecise or extraordinarily precise. Imprecision accords with common sense – and most of the Constitution, frankly. Judge Luttig, for one, calls the idea that the president is not a federal officer “unfathomable.” But smart people (like former U.S. Attorney General Michael Mukasey) have made a strong argument for that very case. Judge Wallace saw the door out offered by the academic debate, and ran through it.

Hers is certainly not the last word. The rulings above will be appealed – the Colorado Supreme Court has already added this to its docket. A dozen or so other cases are still pending in a variety of state courts. And so other judges could interpret “officer” – and for that matter “insurrection” and “engage” – differently. After all, while some January 6 participants have been convicted of seditious conspiracy, the criminal indictments against Trump avoid a specific charge of insurrection. Is incitement enough? The Colorado ruling said so; note, too, that the amendment emphasizes violating one’s oath to the Constitution, not taking up arms against the United States itself. But the definitions matter greatly. It seems inevitable that the Supreme Court will have to settle these questions. Of course, the 14th Amendment has a Section 5 as well – stating that “The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” If Congress had bothered to do so, we might have a clearer route to knowing whether Donald Trump’s reelection campaign is actually constitutional.