Add “lawmaking” to your year-end list of “things that didn’t happen in 2023.” No matter how measured, Congress and the president accomplished very little this year. Even perennial “must-pass” measures stalled out, leaving in budgetary limbo thousands of federal defense and domestic programs and personnel dependent upon Congress for their annual allowance.

Here are four takeaways to help explain Congress’s dismal record.

Taking the measure of Congress

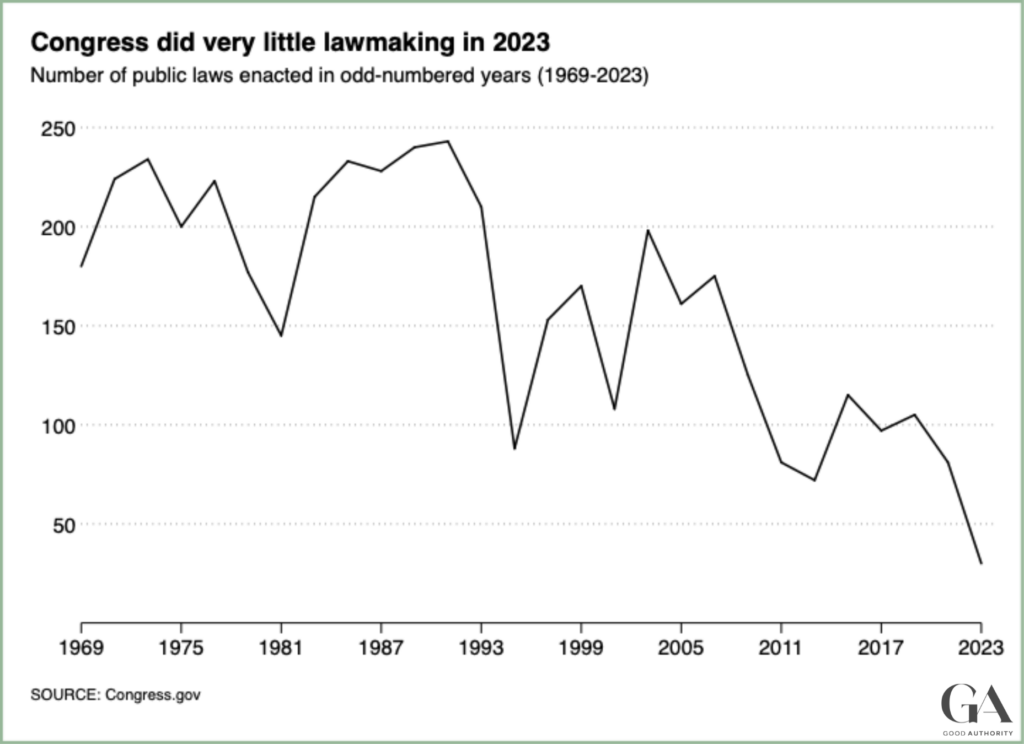

Banner headlines called out this year’s paltry legislative record as a “Capitol Hill stunner” and “Worst. Congress. Ever.” As we wrap up 2023, such claims flow from the strikingly low number of laws enacted this year – 30, at this writing.

As shown in the figure below, it’s the lowest level of lawmaking since at least the start of the Nixon administration, and possibly the lowest number of laws ever enacted in a single year of Congress. Congress and the president reauthorized the nation’s defense programs, lifted the federal debt ceiling, and stopped a government shutdown twice. Other major measures remain in limbo, even some for which a majority of legislators seems to favor action – such as authorizing aid to Ukraine and renewing farm programs.

Even so, judging Congress in 2023 requires more than counting up laws enacted.

We’re only one year into the 118th Congress, so in 2024, legislators might still tackle matters left in limbo this year. Bipartisan Senate efforts to tighten asylum rules and increase deportations – in exchange for Republicans’ votes for aid to Ukraine, Israel, Gaza, and Taiwan – come to mind. Similarly, a special House panel released 150 bipartisan recommendations about U.S. policy towards China, some of which might be incorporated into bills next year.

What’s more, the rise in recent decades of “omnibus legislating” (packing numerous small measures into a single mammoth bill) complicates comparing the number of laws enacted over time. And simple counts treat all laws the same, even though some measures target narrow matters, while others temporarily fund the entire federal government.

Nor can the number of laws reveal whether Congress can solve problems. Better to use a metric like the one I proposed in my book, Stalemate (updated here): I reconstructed the list of salient issues on the nation’s agenda and investigated which ones Congress and the president managed to address (or not) in each Congress since World War II.

Signs of a broken party

Gridlock is common when the parties split control of Congress, especially in an era of intense partisanship, slim majorities, and competitive elections. But something more plagued 2023.

Both Republican speakers this year struggled to build and sustain a durable partisan majority – leading to the historic vote initiated by GOP renegades to boot Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) from the speakership. It took three weeks for House Republicans to settle on McCarthy’s successor. “If we don’t change the foundational problems within our conference,” one House Republican predicted, “it’s just going to be the same stupid clown car with a different driver.”

Not much changed. The new speaker, Rep. Mike Johnson (R-La.), faced the same unruly conference with barely any votes to spare – and his margin of error shrunk even further when the House expelled Rep. George Santos (R-N.Y.).

What went wrong?

House party leaders must build and maintain their “procedural majority” – a term coined decades ago by political scientist Charles O. Jones. As another political scientist, Matt Glassman, explained in our Good Chat this fall, partisans elect a speaker, adopt chamber rules conducive to advancing the party’s agenda, and support the leadership when it sets the floor agenda in the House – even if legislators disagree with the substance of a measure. Such loyalty on procedural votes, political scientist Steve Smith reminds us, is part of a bargain: Leaders seek to accommodate the demands of their rank and file, and partisans in turn support leaders’ stewardship of the chamber agenda.

Neither speaker enjoyed a stable procedural majority. As evidence, 2023 saw the largest number ever of “special rules” defeated on the floor. These are resolutions that party leaders bring to the floor via the Rules Committee to set the terms of debate for, and sometimes rewrite the text of, party-favored measures. In each of the four defeats, members of the hardline GOP House Freedom Caucus (HFC) joined every Democrat to vote against the rule, derailing the GOP agenda and violating the party bargain.

Republicans also won the award (last bestowed in 2010) for the most failed final votes (15). That included two must-pass spending bills, including the annual bill to fund federal farm programs. More than two dozen more moderate GOP sided with Democrats to vote down the bill because it included a provision advanced by conservatives to ban mail and retail pharmacy sales of the abortion pill mifepristone.

Most strikingly, lacking a procedural majority and sufficient GOP votes to adopt “special rules” to lift the debt ceiling, advance major stopgap spending bills, and reauthorize Pentagon programs, both speakers relied on a routine parliamentary move known as “suspending the rules.” Suspensions require a two-thirds, inevitably bipartisan, vote – typically reserved for less-salient measures. That means scores of Democrats did the heavy lifting as GOP leaders abandoned the demands of their party’s right flank. Keep your eyes on this maneuver: repurposing an old practice and relying on a unified minority party to circumvent a majority’s parliamentary mess.

Disruption unlimited

House Republicans this year have openly called themselves “The Five Families,” a not so veiled reference to the five Mafia crime families in The Godfather movies. Under Speaker McCarthy, each family sent a representative to the GOP’s weekly meeting of their Elected Leadership Committee. Of the “five families,” hardliners on the far right are most responsible for derailing the legislative trains. As political scientist Ruth Bloch Rubin puts it, the HFC (and like-minded hardliners outside the HFC such as Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida) deploy a strategy of “collective defection,“ aiming to counter any temptation amongst its members to accept side payments for their votes from party leaders. By limiting its membership to hand-selected true believers (of a MAGA flavor) and running a parallel campaign organization, the HFC functions as a party within a party – leaning on its “party sub-brand” to go to battle with GOP leaders.

Most on-brand for these House hardliners are their repeated and extreme bouts of hardball, or what elsewhere I’ve called playing for legislative keeps. Despite the concessions HFC members secured from McCarthy to ensure his election after 15 rounds of balloting for the speakership last January, hardliners did not become team players. Instead, they defeated party priorities and undermined McCarthy’s authority – and along with it the chamber’s leverage against a Democratic-led Senate and White House.

The most damaging move by the HFC this year was refusing to support the levels of spending stipulated in the agreement that suspended the debt ceiling. McCarthy responded to their threats this summer by abandoning the spending agreement: Specifically, McCarthy gave hardliners a greenlight to cut domestic spending by $100 billion, a draconian decline in spending rejected by many of the HFC’s GOP colleagues, along with senators from both sides of the aisle.

By giving into the HFC, McCarthy set up the House for failure when it tried – but could not muster sufficient votes – to pass numerous of the 12 “must–pass” spending bills; Speaker Johnson didn’t fare much better. Ultimately, GOP leaders had to turn to Democrats for votes to keep the government’s lights on – predictably enraging the far right. In yet another twist and turn, HFC leaders in early December finally relented, abruptly dropping their insistence on additional spending cuts after tying the House in knots over months.

When it came time for HFC elections this month, Rep. Warren Davidson (R-Ohio) bowed out of a leadership role after the group elected Rep. Bob Good (R-Va.) as its chair, since Good is a legislator known to favor scorched earth tactics. “I am concerned that our group often relies too much on power (available primarily due to the narrow [Republican] majority),” Davidson wrote HFC members, “and too little on influence with and among our colleagues.”

Logjams in the Senate

It’s hard to muster a hoop or holler for the Senate either. Senators took hours casting votes, spent two months wending toward bipartisan passage of three looped-together spending bills, and ended the year in a logjam over Republican demands to tighten the U.S.-Mexico border as the price for their votes to aid Ukraine, Israel, Gaza, and Taiwan. It takes two chambers to tango, so perhaps no surprise it was hard to light a fire under senators’ feet.

Of course, the Senate doesn’t need the House to flex its advice-and-consent muscles. So long as a majority of the Senate favors action, the chamber can confirm the president’s nominees for executive and judicial branch positions – even if that happens at the Senate’s slow pace. But individual senators can exercise their procedural right to trip up even the least salient of appointments when such moves serve their goals.

On the judicial side, majorities ruled: The Senate confirmed 71 new federal judges, including a handful in deep red states. Senate Democrats – occasionally with Republican support – made substantial progress diversifying the federal bench. Over Biden’s three years in office, nearly two-thirds of the total 166 confirmed judges are women, about half served as public defenders or civil rights lawyers, nearly two-thirds are people of color, and roughly 40 percent are women of color.

For military appointees, minorities ruled – until one senator folded at the end of the year. Hundreds of Biden’s military nominees piled up on the calendar after Sen. Tommy Tuberville (R-Ala.) began blocking voice votes for their promotions up military ladders. Tuberville thought taking hostages would enable him to force the Pentagon to drop its policy of covering leave and transportation costs for service members seeking reproductive health services out of state.

Think again, the Pentagon said. As months went by, frustrating the services, Pentagon brass, and military families, enough GOP colleagues signaled they would join Democrats to rework the process to speed promotions through the Senate, stripping individual senators of their right to gum up the works – and so Tuberville eventually relented. Even after voice votes enabled confirmation of hundreds of promotions, five high-ranking officials were left in limbo, one of them targeted by Sen. Eric Schmitt (R-Mo.) over concerns about the Pentagon’s diversity commitments – and so those promotions will have to be handled next year.

The congressional roller coaster will surely continue next month, as January and February deadlines loom for making deals on federal spending for the remaining nine months of the fiscal year. Buckle up, and as Rep. Steve Womack (R-Ark.) has advised, keep the barf bag ready.