Shortly after his reelection on Nov. 5, 2024, President-elect Trump vowed to levy a new 25% import tariff on Canada and Mexico once he took office. On Feb. 1, 2025, Trump invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to deliver on this promise. In his address to Canadians that evening, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced a planned response of 25% tariffs against $155 billion worth of U.S. goods.

By Feb. 3, however, both sides announced a 30-day pause on the proposed tariffs. Trudeau agreed to a series of immigration initiatives – many of which were existing commitments – while Trump continued to express interest in Canada becoming the 51st state.

While national leaders in both Canada and Mexico continue to strategize a response that will deter Trump’s aggression and satisfy a vague set of demands, we know that ordinary citizens will pay the costs of a new trade war. How will the Canadian public respond to the conflict?

Could a trade war ease Canada’s growing partisan divide?

The ability of Canadian governments, both federal and provincial, to sustain a trade war will depend on the public’s willingness to bear the economic costs. Federal elections are scheduled for 2025 and several provincial elections will take place in 2025 and 2026, presenting voters with an opportunity to signal their displeasure with Canada’s response.

Canada is increasingly experiencing partisan-ideological sorting, which is when partisanship, ideological identification, and policy beliefs are interconnected. Economic voting is also a frequent feature of Canadian politics and evaluations of national economic conditions as the trade conflict unfolds can influence voting decisions at the polls. My own prior work also suggests that when Canadians think of themselves as citizens rather than consumers, it can limit U.S. firms’ ability to obtain favorable regulations or policies in Canadian markets.

A recent study by Joshua A. Schwartz and Dominic Tierney can help us understand the likely impact of a trade war on Canadians’ views. They argue that two factors increase the likelihood that concrete external security threats will produce domestic political unity and overcome polarization: vividness and elite agreement. To be vivid, the threat must be specific, attention-grabbing, and of emotional interest. As for elite agreement, there must be a domestic interparty agreement about the nature of the threat.

Using survey experiments that focus on how Americans view China’s efforts to become a global military power, Schwartz and Tierney find that the combination of both threat vividness and elite agreement about the threat reduce negative attitudes that partisans feel towards other domestic political parties and their supporters.

First, is the U.S.-Canada trade war “vivid” for Canadians?

There are few threats that would be better described as “vivid” for Canadian citizens. The current trade war poses a direct and substantial threat to the Canadian economy, given the deep economic ties between the two countries. Trade represents two-thirds of Canada’s GDP – and exports alone support 1 in 6 Canadian jobs. More than 77% of Canadian exports are headed to the United States.

Canadians typically view free trade as both necessary and beneficial to Canada, public opinion polls show. Other than the years of the first Trump administration, Canadians have viewed the U.S. favorably. For the past 20 years, more than 80% of Canadians have consistently supported the position that trade was becoming more important to the Canadian economy. Similarly, in 2022, more than 80% of Canadians supported North American free trade.

The opening exchange of the trade war has dominated media headlines and prompted responses from political representatives at all levels of government. There is a clear emotional resonance to the crisis. Expressions of betrayal, anger, and heartache color much of the current media coverage and political statements. Responses from leaders have expressed dismay at “find[ing] ourselves at odds with our best friend and neighbour” and the “betrayal of America’s closest friend, of your ally, your neighbor, your best partner in the whole world.” The president of Canada’s Customs and Immigration Union described the immigration initiatives as “border theatre” while other political leaders described President Trump’s claims about the Canadian border as “bogus.”

Is there elite agreement among Canadian officials?

At least at this initial stage, politicians across Canada’s political spectrum have found common ground. Trudeau resigned as party leader in early January, but remains prime minister until his successor is elected. The Liberal Party faces a tough federal election. The leadership race between former Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland and former Bank of Canada governor Mark Carney has since been dominated by the trade dispute with the U.S. and both candidates support “dollar for dollar” retaliatory tariffs. Pierre Poilievre, leader of the federal Conservative Party and front-runner in the next federal election, supports a similar position. That election must take place by October 2025, but many believe a no-confidence vote will prompt an earlier federal election.

Across the country, provincial leaders have largely lined up in support of an aggressive response to U.S. tariffs. Doug Ford, Ontario’s Conservative premier, triggered a snap election to secure a mandate to confront Trump (after previously wearing a “Canada is Not for Sale” baseball cap at a press conference). Ford declared, “No matter what political stripe you come from, in Canada, we’re united. We’re a united country, and we’re a proud country.”

It’s not just cheap talk. Provinces across the country began removing U.S. liquor brands from store shelves. In British Columbia, New Democratic Premier David Eby announced a ban on liquor specifically from Republican-led U.S. states. In Nova Scotia, the Liberal Party and New Democratic Party expressed support for Conservative Premier Tim Houston’s plan to exclude U.S. businesses from provincial procurement, increase tolls on U.S. commercial vehicles, and begin to diversify the economy away from the United States.

Canadians show early signs of rallying-around-the-flag

The full response of the Canadian public will be seen in the coming days and weeks. While we wait for new public opinion data to be collected after the flurry of political moves this weekend, the loud booing of the U.S. national anthem at professional hockey and basketball games in Ottawa, Toronto, and Calgary may offer an indication of what to expect.

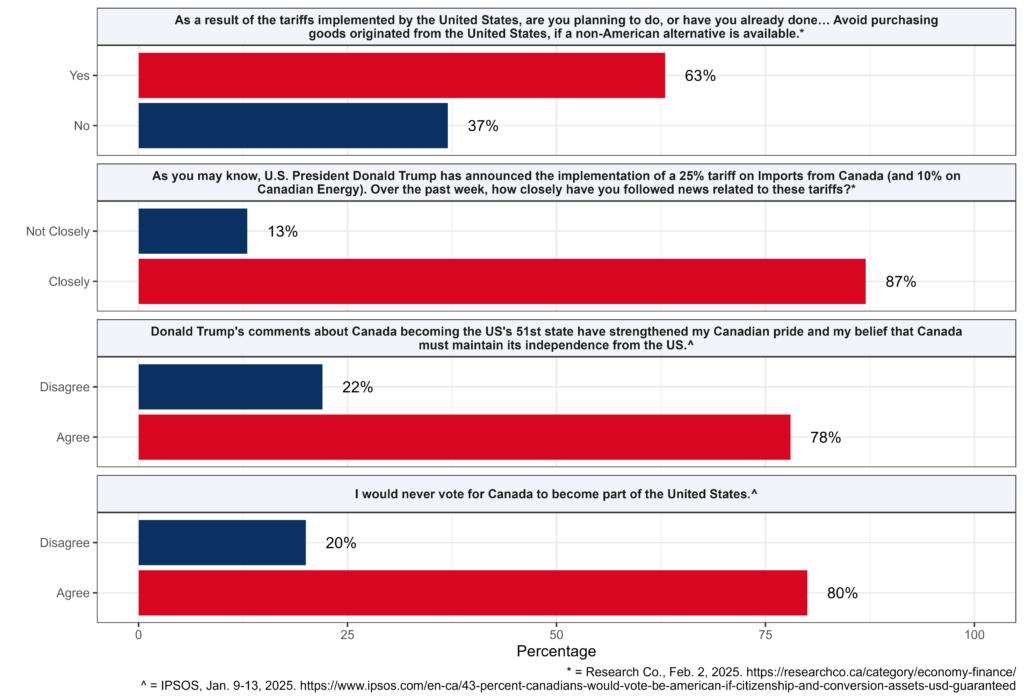

Public opinion firms have tried to pinpoint Canadian attitudes toward the ongoing conflict, primarily using online, opt-in samples of Canadian adults. So far, the findings shared by firms like YouGov, Research Co., and Ipsos (some of which are shown in the figure below) paint a consistent picture. Canadians are paying very close attention to the conflict and are unified in their views. Canadians are also clearly opposed to the idea of becoming the 51st state in the U.S.

In Trudeau’s Feb. 1 address to his country, he quoted President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 speech to the Canadian Parliament:

Geography has made us neighbors. History has made us friends. Economics has made us partners. And necessity has made us allies.

Notwithstanding the efforts of Trudeau and others to link the U.S. tariffs to the Trump administration – and not the American people – the conflict has thrown the relationship into a darker light for Canadians. It remains to be seen how Canadians will evaluate this long-standing partnership once the crisis passes.

Tyler Girard is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at Purdue University. His research focuses on the international political economy of digital technologies and the shifting politics of global trade.