On Friday, incumbent President Mokgweetsi Masisi was sworn in for a new term, following a general election that gave his Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) every reason to worry. In the lead-up to Botswana’s Oct. 23 elections, main opposition leader Duma Boko confidently changed his Twitter handle to “Incoming President of Botswana.”

To many analysts, conditions appeared ripe for the country’s ruling party to succumb to electoral defeat after 53 years in power. BDP’s popular vote share had been steadily declining since independence in 1966. In 2014, the party managed just 46.5 percent of the vote, an all-time low. Meanwhile two opposition parties, Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC) and Botswana Congress Party (BCP), received a combined 50.4 percent of the vote.

BDP faced several challenges in 2019

UDC and BCP announced in 2017 they would join forces under the UDC banner to participate in the 2019 elections. Here’s why this coalition posed a serious threat to the BDP’s rule. Had UDC and BCP voters combined their votes in 2014 to back a single parliamentary candidate in each constituency, they would have won a 33-seat majority in Parliament, unseating BDP from power.

The 2019 elections also marked the first time Botswana’s ruling party could not rely on superior campaign resources. BDP’s campaign war chest traditionally allowed the party to run circles around opposition parties, but Masisi’s anti-corruption commitments resulted in a decline of party donations from lobbyists and big businesses. At the same time, UDC collected vast sums of cash, largely from outside business interests.

A further challenge came from former president Ian Khama, who launched his own political party, the Botswana Patriotic Front (BPF), after falling out with Masisi. In May 2019, Khama recruited a little-known legislator as party president, and managed to persuade his younger brother Tshekedi Khama to defect from BDP to join the newly created BPF. As tribal royalty and sons of BDP founder and first president Seretse Khama, the Khama brothers wield significant influence in their home region surrounding the town of Serowe, a traditional BDP stronghold. Analysts predicted that Ian Khama’s move would then split the BDP vote.

But the BDP had a strong showing at the polls

The final vote count gave BDP its 12th consecutive victory, with almost 53 percent of the popular vote — and 38 out of 57 parliamentary seats. UDC received 36 percent of the vote and won 15 seats. The Alliance for Progressives (AP) and BPF garnered 5 percent and 4 percent, respectively.

The robust showing for the BDP caught many by surprise. The UDC ended up with two fewer seats than in the 2014 Parliament — and UDC leader Boko lost his own seat to a BDP rival. Khamas’s BPF won three seats around their hometown and may have cost the BDP an additional six seats by splitting the vote.

How did BDP do it?

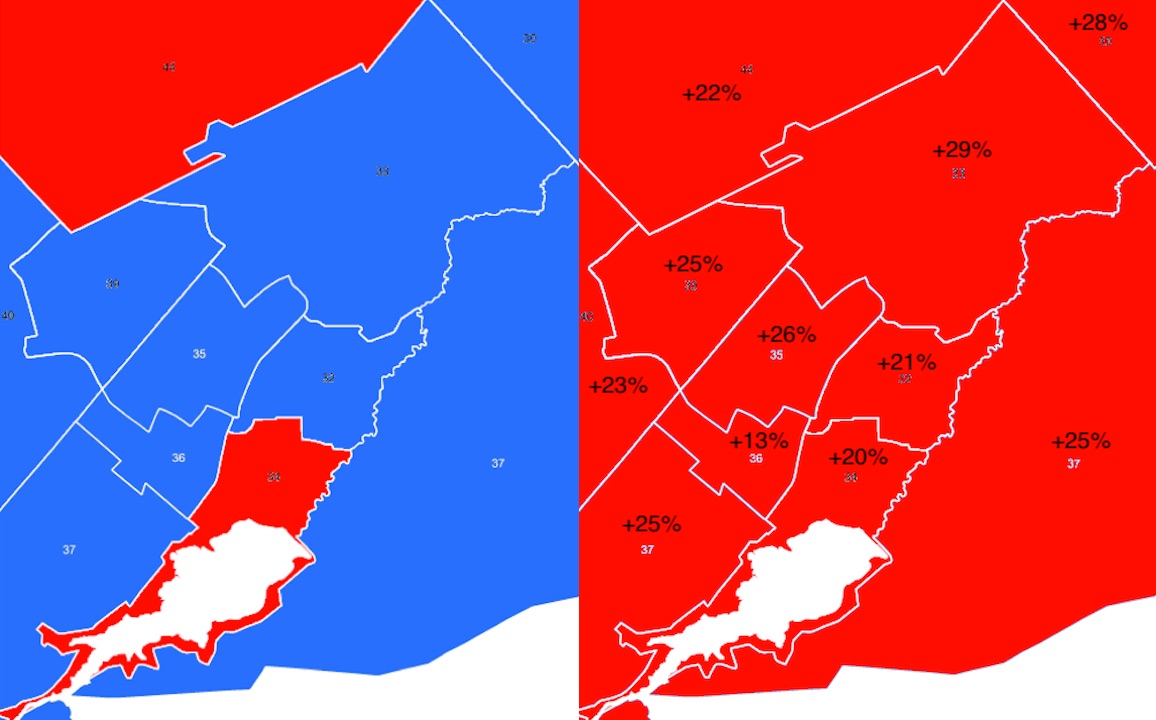

The crucial factor was a surge of support primarily from the southern region of the country, including the capital, Gaborone. Across Africa, urban areas have traditionally provided crucial footholds for opposition parties, which rely on support from more-educated and reform-minded citizens. In 2014, in fact, UDC won all but one of Gaborone’s core constituencies (see figure).

Source: Paul Friesen

Data: The Voice, https://news.thevoicebw.com/election-results/.

That didn’t happen in 2019. BDP crushed the UDC in Gaborone, gaining between 13 and 29 percent in vote share around the city. Why did this happen? Analysts continue to look at the various causes behind this shift, but there are several leading hypotheses.

In a few constituencies, the new opposition party AP possibly cost the UDC some seats through vote splitting, but the primary explanation centers on the three dominant political players — Masisi, Boko and Khama.

Aside from his political base, Ian Khama is fairly unpopular. Many in Botswana saw his 2008-2018 administration as authoritarian, overly conservative and corrupt.

When Masisi — Khama’s handpicked successor — came into power in 2018, the new president immediately began distancing himself from Khama’s legacy. Masisi reversed unpopular policies, launched corruption investigations and increased interactions with citizens. Masisi projected a fresh, relatable and reform-minded image, summarized by his campaign slogan, “Rebirth of the BDP.”

UDC leader Duma Boko, meanwhile, saw several of his party’s high-risk election strategies backfire. Boko’s campaign took a populist approach, attempting to channel the anger of voters frustrated with the lack of economic opportunities. He promised to end unemployment in one year and increase the minimum wage threefold.

Boko also engaged in strong rhetoric and personal attacks, prompting some voters to draw comparisons with Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign. In a closely watched presidential debate a week before the election, many in Botswana saw Boko’s harsh language and political assaults as unpalatable.

Ahead of the election, Khama’s BPF pledged its ultimate support to the UDC, putting Khama and Boko into an ill-fated partnership. Some voters likely saw Boko as Khama’s Trojan horse — with the alliance as Khama’s attempt to regain political control.

Gaborone, home to many educated professionals, thus had the option of voting for the reform-friendly Masisi, or for Boko, an unpredictable populist backed by an unpopular former president. Gaborone’s voters resoundingly chose Masisi — despite having backed the opposition in 2014.

Are there takeaways for elections in neighboring countries? While the urban centers of Botswana threw their support behind a longtime ruling party, this may not happen elsewhere. Botswana, Africa’s oldest continuous democracy, is more democratic and economically developed than most countries in the region.

The election also highlights the effectiveness of a key strategy many ruling parties in the region adopt — strict adherence to term limits. Leadership change tends to cast longtime ruling parties as more democratic. In Botswana, Masisi was able to create a stark contrast with the regime of his predecessor, a move that helped BDP renew its image and win back many voters.

Paul Friesen is PhD candidate and Kellogg Institute fellow at the University of Notre Dame. His research focuses on partisanship and elections in southern Africa. Follow him on Twitter @Paul_Freezy.

Note: Updated Oct. 3, 2023.